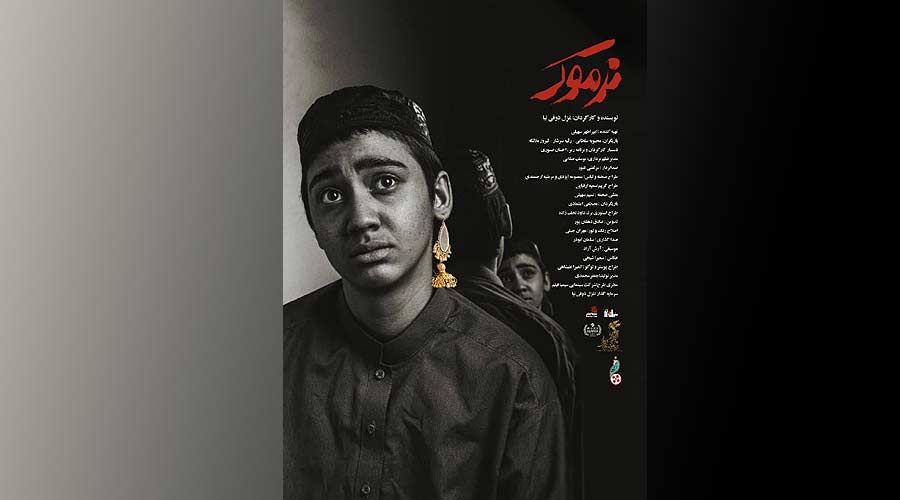

Comprehensive Analysis of the Film "Narmook" by Ghazal Zoghinia: An Exploration of Identity, Gender, and Resistance in the Context of Tradition Story Summary

Narmook, the story of a denial

The short film “Narmook,” directed by Ghazal Zoghinia, is a work that, with a realistic perspective on the outskirts of Mashhad and within the cultural context of the Chalo tribe of the Baloch people of Afghanistan, presents a deep and multi-layered narrative of the confrontation of individual identity with social pressures and restrictive traditions from the life of Malaleh, a young girl.

According to Artmag.ir, due to the superstitious belief that girls should dress up as boys in order to have a son, she has lived for years without her will and only at the request of her family, with a boyish identity and in their clothes, and has shared in the passionate games of childhood with boys. But now, as she reaches puberty and menstrual blood is revealed on her bicycle saddle, this freedom suddenly collapses and she must return to her true feminine role.

By imposing a girl’s identity, family and society push her from the unfettered world of childhood to the cage of gender restrictions and eventually forced marriage, taking the conscious viewer to a layer beyond a childish story.

Malaleh, in the face of this compulsion, rebels from passivity and, by cutting her hair and removing her makeup, displays a symbolic resistance to oppressive traditions.

With its indigenous atmosphere, impressive acting, internal characterization, subtle symbolism, and distinctive visual aesthetics, the film invites the audience on an emotional and intellectual journey that raises deep questions about identity, freedom, and gender roles in the audience’s mind, portraying the bitter transition of identity and narrating a story that, while seemingly simple, contains deep emotional and social complexities.

“Narmook” took a big step by appearing at the Tehran Short Film Festival and the Fajr Festival, but with its depth, it could have received much more attention.

I saw “Narmook” for the first time at the Rasht National Film Festival. With the short review I wrote there, Ms. Zoghinia kindly provided me with the link to the film so that I could watch the film several times and come to this note.

In this article, relying on the theories of narratology, gender, and body cinema, the thematic layers, form, and ideology hidden in the film are analyzed.

Introduction: Entering Malaleh’s World

“Narmook” begins with vibrant images of the concrete alleys on the outskirts of Mashhad, where children from the Chelo tribe are immersed in a lively atmosphere, riding bicycles, playing marbles, pushing tires, competing, laughing, and rushing.

Malaleh, dressed in a boyish brown dress, is at the center of this cheerfulness, but behind this seemingly innocent frame, there are signs of oppression, and this oppression manifests itself in the main turning point of the story, the blood stain on the bicycle saddle. This moment is not only a biological event and a sign of her sexual maturity, but also an identity rupture and social crisis, throwing her from the free world of childhood towards social restrictions and deeper conflicts.

What follows from here is a narrative of “returning the body to the rules of tradition.” Malaleh, who has been dressed and accepted as a boy, must now submit to the re-creation of being a woman; not out of personal desire, but out of social obligation.

Although in the first shot we see that the leather leaf of the bicycle saddle has been torn off, when Malaleh gets off and puts her hand on it to ride it, the blood stain on the bicycle saddle and Malaleh’s clothes is not visible and everything is normal and natural. When she throws the bicycle next to her father, the father’s friend and companion notices the blood on the saddle, and this is a visual error in the set design.

The film delicately transforms this transition into a dramatic journey in which Malaleh is caught between the boyish identity she has lived and the girlish identity that is imposed on her.

What follows is a narrative of denial, resistance, and rebellion against oppressive traditions, which, through powerful visual and narrative language, forces the audience to reflect on the meaning of identity and freedom.

This analysis, with a meticulous and scientific perspective, examines the dramatic structure, believability, characterization, performance, mood, symbols, and ideological implications of the short film “Narmook” in order to reveal the hidden layers of this work to readers.

Worldview and Theme

The worldview of “Narmook” is rooted in a feminist and humanistic critique of patriarchal structures and restrictive traditions. The film depicts a world in which individual identity, especially women’s gender identity, is under constant surveillance and control by society. This view is consistent with Judith Butler’s (1990) theory of “gender performance,” which sees gender not as a natural truth but as a learned and imposed role that is reproduced through everyday actions and social surveillance.

In “Narmook,” Malaleh’s body becomes a battleground between her personal desires and the social norms and gender systems of her environment. Where her freedom is suppressed by puberty and the imposition of a girl’s identity. Her body is hidden, covered, punished, and trained to resemble what others define.

Being a woman is not a natural fact, but a role learned, practiced, and internalized, by walking, sitting, tying a scarf, and even looking at the ground. Malaleh is not a girl who has become a boy from the very beginning, but a girl who has been forced to be a boy.

The main theme of the film is the confrontation of individual identity with imposed traditions, but this confrontation goes beyond a personal story and reaches a social critique of gender values in traditional societies.

The superstition of dressing a girl as a boy to give birth to a boy, which is revealed in the conversation between women during Eid, not only distorts Malaleh’s identity, but also shows the higher value placed on boys in traditional culture. This theme is subtly reinforced in scenes such as the different treatment of their little son at the table by parents, compared to girls, or the mother’s dialogue about “the value of a woman in the gold her husband gives her.”

However, the film avoids sentimentalism or mere victimization. Malaleh, as Tessa de Graaf argues in Cinema and Feminism (2007), becomes an activist rather than a passive victim, who, in the final act, cuts her hair and removes her makeup, demonstrating symbolic resistance to forced marriage. This action is reminiscent of Malaleh Yousafzai, the Pakistani girls’ rights activist whose name lends the character a symbolic burden of resistance to gender oppression.

However, the lack of deeper exploration of the inner motivations of the mother, who is both a victim of tradition and a representative of and perpetuator of the structure, limits the opportunity for a more multi-layered critique.

The mother’s key dialogue in the makeup sequence: “Look how beautiful you have become. Isn’t it a shame to go play with the boys with this beauty?” reveals the suspense point of the mother/daughter relationship: a relationship based on beauty as a value and submission as a way of survival, and this dialogue is the manifestation of the hegemonic view of women; women not as human beings, but as subjects of decoration and subordination.

Malaleh, in the face of this re-creation, has only one tool: rebellion. The film, rightly, dedicates the ending to this rebellion; of course, not with victory, but with resistance.

Narrative and Dramatic Structure

“Narmook” uses a classic three-act structure and linear narrative, which, according to Robert McKay in “Story: Structure, Style, and Principles of Screenwriting” (1997), provides a solid foundation for character-driven dramas.

The first act introduces Malaleh’s free, boyish world. She is immersed in a lively, uninhibited atmosphere, riding a bicycle, playing marbles, and pushing a tire. The fast rhythm, open frames, and warm colors convey a sense of childhood joy and quickly draw the audience into Malalehs world. The first dramatic turning point, the discovery of blood on the bicycle saddle, breaks the balance of this happy, boyish world and introduces an identity crisis. This crisis comes to her not from the character’s internal questions, but from external, socially imposed relationships.

In this film, it is not an external event but a socio-psychological moment: the disappearance of the right to play, simultaneously with the appearance of blood on the saddle; this moment, in the words of Gérard Genette in “Narrative” (1972), is the “trigger of the dramatic transformation” that drives the story towards deeper conflicts. The confrontation of Malaleh’s free identity with the family and social expectations to conform to traditional gender roles.

The second act deepens the conflict, with the family’s pressure to return Malaleh to her identity as a girl. Scenes such as being forced to bathe, wearing girls’ clothes, burning boys’ clothes, training in “girlhood” by practicing walking and looking at the ground (which is reminiscent of Hollywood and Western fashion shows, but fundamentally different from them), locking the bicycle in a shed, and finally dressing up and preparing for the female social performance during the Eid ceremony (although we have little information about the purpose, how, and why of holding this Eid) form the dramatic climax of this section.

This process, according to Michel Foucault in “Discipline and Punishment” (1975), shows the “discipline of the body” that reconstructs Malaleh’s identity through surveillance and punishment. The film depicts it intelligently, with a touch of bitter humor and Eastern melancholy (in this scene, although Malaleh has embraced the path of submission to her mother’s condition, she occasionally throws a stone into the pond, creating waves of dissatisfaction and protest).

The third act reaches an emotional climax with the wedding ceremony and Malaleh’s final resistance. This transformation is not the result of an inner journey but a final rebellion; a kind of rebellion compressed into silence, in the broken mirror frame, and in the woman standing before the onlookers with her hair cut short and makeup removed, the open ending leaving the audience to ponder her fate.

Believability and Dramatic Logic

Believability, as one of the main elements of drama, is, according to David Bordwell in his book “Narrative in Fiction Film,” dependent on the work’s ability to create a coherent and logical world.

“Narmook” is rooted in the creation of a local and tangible space. Cultural details such as local games, the colorful costumes of the Afghan Baluchis, traditional rituals such as women smoking hookahs, and the body language of the characters create an authentic world. These elements, according to Laura Malloy in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), enhance the sense of immersion.

The superstition of cross-dressing, which is revealed in the conversation of women at Eid ceremonies, is naturally rooted in the cultural context of the story but does not impose it on the natural context of the drama, but rather flows from the characters and the local world. As Louis Giannetti says in Understanding Film (2001), “Drama is at its peak when motivations arise from an internal logic, not from external interference by the author.” “Narmook” justifies the characters’ motivations without external imposition.

However, some inconsistencies undermine credibility. The newly watered yard in the absence of the mother and sisters, all of whom were present at the Eid celebration, does not fit the logic of the story because no one is home and it is not the father’s business. These details, however small, weaken the sense of coherence. Also, Malaleh’s transformation from resistance to apparent acceptance of her girlhood in the scene where she descends from the rooftop and her mother stipulates that she will give her bike back if she attends the Eid celebration like a good girl.

This very statement brings Malaleh to the hairdresser’s scene without resistance, insistence, or denial. This transformation seems rushed without showing enough internal process.

According to Syd Field in “The Screenplay” (1979), the character’s development should be depicted through gradual choices and actions. If the film had shown Malaleh’s moments of questioning and hesitation or inner conflict, her development would have seemed more natural and the audience’s emotional connection with her would have been deeper.

Also, Malaleh’s being alone in the crowded market and the men’s mocking glances and laughter are a little questionable in terms of the logic of the situation. Given all the family’s sensitivity to Malaleh’s social “performance,” how could they leave her alone in such a place? And that’s right after the hair salon and earring-buying sequence. This break in the narrative is clearly felt and disrupts part of the coherence, and the audience does not know whether this is Malaleh’s delusion or an illogical reality.

Characterization

Malaleh, played by Roghayeh Sarshar, is the emotional heart of the film and the main character and central actor. She is a multifaceted character caught between boyish freedom and the pressures of girlish identity.

Far from the usual sentimentality, the film presents this character as neither oppressed nor rebellious, silent and stubborn. She is neither a mere victim nor a stereotypical hero. Her physical reactions (kicking, pushing, climbing the roof, looking through barred windows) take on a symbolic function, presenting her not simply as a victim but as someone trying to reconstruct her identity.

She is a girl who finds meaning in her childhood world, through play, bicycle, competition, and shouting, and now, with her female body, she must give up that meaning. Her angry and resentful gazes when confronting her mother, her bewilderment in the barbershop scene, and her final act of cutting her hair show the emotional depth and rebelliousness of the character. This complexity, according to Gerard Genette in “Narrative” (1972), transforms Malaleh into a character who is not a passive victim, but an activist in search of her own identity.

The secondary characters, especially the mother and father, although typical and faithful to traditional models, are not one-dimensionalized in the film’s treatment. The mother, played by Mahboobeh Soltani, is a combination of authority and fragility. She is both a victim of tradition and a perpetuator of it.

The mother is a complex character who sometimes caresses and sometimes threatens; Sometimes she fixes the headscarf, sometimes she sets the clothes on fire. At moments in the film (for example, in the girls’ education or the hairdressing scene) she appears affectionate and sometimes playful, her affectionate tone in the girls’ education actually heralding the gradual death of Malaleh’s identity. Her key line of dialogue (“Did I do wrong to let you be free for so many years?”) reveals her ambivalence, and provides a deeper opportunity to explore this ambivalence, but its excessive brevity creates a sense of incompleteness. If the film had shown more moments of hesitation or remorse for the mother, this character would have been more complex and sympathetic.

The father, played by Firouz Malaekeh, carries, in silence and violence, the masculine shame that comes from the pressure of custom. His diminutive presence, while consistent with the logic of the story, limits the opportunity to explore the impact of custom on men.

Other supporting characters, such as the women at the Eid ceremony, serve as social catalysts, effectively representing collective pressures. The woman who advises cross-dressing serves as a symbol of deep-rooted traditions.

Performance and Acting

The acting in the short film “Narmook” is one of the main strengths. Ruqayya Sarshar, as Malaleh, conveys the emotional depth of the character with her delicate movements and facial expressions. She carries a character who must be both a boy and a girl, a child and a teenager, a victim and a hero. The scene where she draws an exaggerated mustache on her lips with her fingers blackened from washing the pot is a brilliant example of an actor conveying, without dialogue, a sense of oppression and an attempt to reclaim her identity. This moment, with deliberate exaggeration, shows a physical resistance to “body discipline.”

Mahboobeh Soltani, with her combination of authority and emotion, makes the mother believable and gives a beautiful performance. The supporting actors, especially the children, contribute to the film’s dynamism by being natural in their play scenes. And, despite the inherent danger of playing children, they are natural, unassuming, and believable.

Direction and Editing

Ghazal Zoghinia’s direction of “Narmook” combines attention to vernacular details with the creation of powerful visual moments. Using real locations, such as concrete alleys, a poor courtyard with clotheslines, and a bustling bazaar, he creates a tangible and authentic world. Precise framing, such as the scene where Malaleh is placed between two rows of hanging clothes and a colorful curtain after being thrown into the courtyard, visually conveys the maximum pressure of tradition and social surveillance in a triangle. This image, which places Malaleh in a visual fist, conveys a sense of suffocation and limitation to the audience. It seems that with her back and sides closed, there is only one way left, and that is to merge with her mother, who is sitting across from her.

Mohammad Seddigh Dehghanpour’s editing is one of the film’s strengths. With smooth, fluid cuts, he maintains the rhythm of the story. The transition from Malaleh’s circular bike ride in the yard to the men’s circular dance at the wedding not only shows the passage of time, but also visually represents the recurring cycles of limitation. This cut, according to David Bardwell in “Narrative in Fiction Film” (1985), reinforces the sense of narrative coherence through visual and conceptual continuity.

However, the same direction of the two movements (counter-clockwise) misses the opportunity for conceptual depth through visual contrast. If the direction of the men’s dance had been opposite to Malaleh’s, the contrast between her individual freedom and the restrictive social cycles would have been conveyed more visually.

This reference to Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s “Bicyclist,” with Malaleh’s circular movement, is a clever homage to Iranian social cinema that reinforces cycles of restriction. This creative editing, as Laura Marx notes in “The Skin of Film” (2000), evokes a tactile and emotional sense in the audience.

However, some cuts, such as the transition to Malaleh in the market, are ambiguous due to the lack of background and disrupt the coherence. It is unclear whether these taunts are real or an illusion caused by Malaleh’s anxiety.

If this scene had been accompanied by more visual cues of Malaleh’s inner turmoil, it could have been interpreted as a reflection of her inner turmoil and added psychological depth to the story. And if this shot had been removed, it would not have detracted from the film due to its extreme brevity and lack of clarity.

Visual aesthetics

The visual aesthetics of “Narmook” are a blend of vernacular realism and subtle symbolism. Yousef Safaei’s cinematography, using natural light and the warm colors of the region, reinforces the sense of vernacular. The brown of Malaleh’s boy’s dress, associated with soil and freedom, creates a meaningful contrast with the blue and red of the girl’s dress, which refer to the limitations and shame of puberty. This choice of colors, according to John Berger in Ways of Seeing (1972), helps to reinforce the film’s gendered and emotional narrative.

The scene of the burning of the boys’ clothes, with orange flames in the gray courtyard, and Malaleh’s gaze from behind the bars of the window, is one of the film’s most powerful visual moments, depicting the end of an identity and the triumph of tradition. Similarly, the broken mirror, which shows Malaleh’s face in fragments, reinforces the sense of identity fragmentation through a combination of low light and shadow.

However, some visual choices, such as the painting of a woman looking at Malaleh, are too stark and lack the necessary subtlety. If the lighting in the interior scenes had been designed with more contrast, the emotional depth of the moments would have been enhanced.

The set and costume design are also strong points. The regional costumes, hanging clotheslines, bold colors, and contrasts between inside and outside the house all provide a visual platform for the narrative of gender and class distinctions. The framing also reinforces the sense of isolation by emphasizing the distance between Malaleh and others.

Mood and Atmosphere

The mood of “Narmook” oscillates between the joy of childhood and the weight of social pressures. Arash Azad’s music, with its indigenous rhythms and ambient sounds such as clapping and banging, beautifully reinforces this duality. The opening scenes, with their energetic music and bicycle bells, convey a sense of freedom, while the sad ending music, with Malaleh’s bittersweet singing in the chorus, instills a heavy emotional charge. Salman Abuzar’s sound design also adds dramatic depth by using silence at key moments.

Symbols and Metaphors

“Narmook” is full of meaningful symbols. These symbols are not decorative, but components of the narrative structure. The film, avoiding superficial symbolism, embeds these signs within the action and story.

Malaleh’s bicycle, a symbol of freedom and mobility, is contrasted with girls’ clothes that indicate restriction. The burning of Malaleh’s boys’ clothes is a metaphor for the erasure of a free past and the end of an era in Malaleh’s life. The erasure of history and the beginning of the fabrication and reconstruction of order, while the girls’ clothes remain on the line, proclaiming the triumph of tradition.

The scene where the mother hen cleans and cuts off her feet is a metaphor for the plucking of Malaleh’s feathers and the restriction of her mobility. This symbolism culminates in the shaky scene of Malaleh walking in girls’ shoes, where her precarious and unstable position reveals the beauty of the fragility of an imposed identity. The broken mirror refers to her identity gap. The fragmentation of identity, the refraction of the self. The black pot is a symbol of her repressed soul, which cannot be erased or whitened.

The first scene of the mother in the yard is accompanied by washing the family’s clothes and is completed by cooking and cleaning the chicken, and in a way it is reminiscent of the term “wash and dry” for women, and in washing the black pots, this task has been transferred to Malaleh.

The ending, with her hair clipped and makeup removed, highlights Malaleh’s feminine activism and demonstrates a symbolic resistance to forced marriage. This moment, reminiscent of the proverb “A loss is always a gain when you avoid it,” gives Malaleh a power that goes from passivity to rebellion.

The black mustache drawn with a dirty finger, an exaggerated reproduction of male power in the body of a humiliated woman who is attached to a poster of a beautiful woman in a hairdresser’s, and then the tying of the mother’s face. If the image of Malaleh’s tying of the mustache were cut directly from the tying of Malaleh’s lips, the symbol, meaning, theme, and effect of the image and editing would be much stronger.

Conclusion: Rebellion, even if silent

“Narmook” is a bold work that tells an impressive story with layers of subtext, with local atmosphere, brilliant acting, distinctive visual aesthetics and deep symbolism. Its strengths are in the performance, creative editing and local feel that make it a successful film, although it has not been seen as it deserves.

“Narmook” shows us that identity, although seemingly unselectable, there is always room for rebellion, for cutting hair, for standing up.

Malaleh’s resistance in the end, although it may not lead to results, is the very “saying no” that is the important possibility that dominant narratives try to suppress.

“Narmook” is more than a film about girlhood, it is a work about possibilities; the possibility of living in suspense, between two roles, two genders, two worlds. With brevity, depth, and narrative simplicity, the film depicts a world in which the girl’s body is not the beginning of liberation, but an alarm bell of limitation.

Zoghinia, by avoiding sentimentality, mere allegorical imagery, or a victim-oriented perspective, has succeeded in presenting in her first work a delicate, poignant, and brilliant narrative of the passage of gender, tradition, and self; a narrative whose voice Malaleh’s voice lingers in the ear. A continuous whistle of endless pain.

“Narmook” is, at its first layer, a narrative of the transition to puberty, but at its core, a story of denial and rebellion. Through a simple and indigenous story, the film moves towards universal concepts such as identity, freedom, body and power.

Rather than forcing Malaleh to surrender, Zoghinia’s film boldly places her in a position where even if she cannot escape, she at least stands. And this standing is the cinematic moment that remains in the mind.

“Narmook” is not only a story of a girl on the outskirts of the city, but also a mirror that places identity gaps and social pressures before our eyes and forces us to rethink tradition and freedom.

“Narmook” is not about menstruation, not about bicycles, not about sewing women’s clothes. This film is about the possibility of saying no.

About the moment when a girl with a blackened face, a broken mirror, stands alone in front of dozens of people who have come to turn her into someone else’s wife. In this standing, she is neither a hero nor a victim; she is simply no longer “Narmook”

References:

• McKay, Robert (1997) Story: Structure, Style, and Principles of Screenwriting

• Bradwell, David (1985) Narrative in Fiction Film

• Malloy, Laura (1975) Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen

• Field, Syd (1979) Screenplay: Fundamentals of Screenwriting

• Genet, Gerard (1972) Narrative Narrative

• Foucault, Michel (1975) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison

• Butler, Judith (1990) Performing Gender: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

• Du Graaf, Tessa (2007) Cinema and Feminism: Theoretical Perspectives

• Giannetti, Louis (2001) Understanding Film

• Marx, Laura (2000) The Skin of Film

• Berger, John (1972) Ways of Seeing