I haven’t just photographed the moon / My job is to record, not rescue!

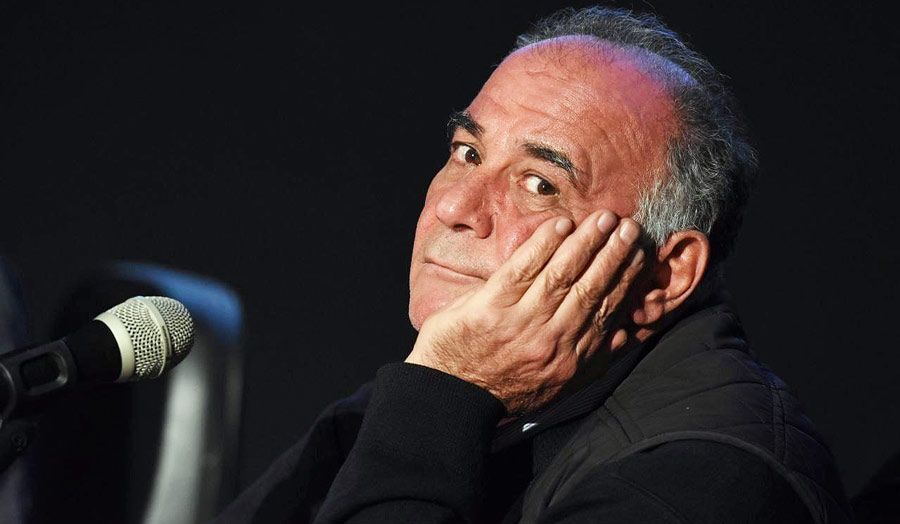

Alfred Yaghobzadeh, is a photographer who has captured pure human moments from the streets of the revolution to the battlefields; without judgment, without pretense, and with a concern for recording reality. In this interview, he talks about his professional path, the changes in the world of photography, and today’s challenges, including artificial intelligence.

According to Artmag.ir, quoted by Borna News Agency, in the rapidly changing world of media, Alfred Yaghobzadeh’s name, as one of the most prominent figures in documentary and war photography, is associated with images that cry out human suffering from the depths of destruction.

Born in Iran and residing in France, Yaghobzadeh has been on the front lines of the world’s humanitarian crises for more than four decades, narrating moments that most cameras fail to capture. He has not only witnessed events but also created images that have become etched in the collective memory of the world; images that are more than narrative, they are truth.

Despite years of working in the context of conflicts and critical spaces, Yaghobzadeh has never considered himself a judge of events. He emphasizes professional impartiality and believes that the work of a photographer is to record reality, not to issue a verdict. In the following interview, he speaks frankly and openly about his experience living on the battlefields to his reflections on technological changes in the world of photography, from the emotional effects of his work on the individual psyche to ethical concerns in the age of artificial intelligence.

My entry into photography was completely accidental

I know that you have spoken many times over the years about the beginning of your path in photography, but what is important to me is to understand the course of your intellectual and artistic development. Can it be said that there was a specific philosophy or approach to your work that guided your path?

There has never been a predetermined philosophy in my work and I have always tried to do my job in the best possible way. My entry into photography was completely accidental. Initially, I intended to graduate in interior design and prepare for architecture, but at the same time, classes were closed at the same time as the revolution, and I was on the streets like many others. Gradually and completely instinctively, I began to record images of the revolution with a simple camera. I gradually distanced myself from the space of education. After the revolution, due to the complex political and social conditions and ultimately the outbreak of war, I immersed myself more and more in the space of documentary photography. I didn’t have much specialized knowledge about photography, but I gradually became attached to this profession. Fortunately, since I had grown up in an artistic family and had a background in painting, sculpture, and drawing, I was relatively prepared from an aesthetic perspective, which helped me a lot.

Then, given the social and cultural conditions prevailing in Iran, I felt that I was no longer able to continue working in that space. I decided to leave Iran and first went to France. My first work experience abroad was in Lebanon; a trip that was my first encounter with Europe and also my first documentary project outside of Iran. Initially, I did not intend to stay in France, but circumstances turned out in such a way that my life path changed. The experience of the Lebanese civil war, given my background in covering the Iranian war, was familiar to me and I was able to face it well.

Lebanon was a real school for me

Can we say that Lebanon was a launching pad for your more serious entry into the international photography scene?

It definitely was. Lebanon was a real school for me. I had entered photography in Iran in a discontinuous and unplanned manner, but after leaving the country I knew I had to work professionally. During my two and a half years in Lebanon, I not only learned a lot experientially, but also provided me with very valuable opportunities. Working with SIPA Agency and Newsweek magazine allowed me to present myself internationally and I experienced significant progress in a short period of time.

Human life was more interesting to me than death and destruction

After that period, it seems that your perspective went beyond just covering war. What caused this change in approach?

After returning to France from Lebanon and continuing to work with SIPA Agency, I came to the conclusion that war is only a small part of human life. My perspective gradually changed from merely capturing scenes of conflict and violence to capturing everyday human life. From patients in the operating room to fashion, from political figures to ordinary people in the streets and markets, all of these became relevant to me. In fact, human life was more fascinating to me than death and destruction. To be honest, the only place I haven’t had the opportunity to photograph so far is the moon.

It’s interesting that you mentioned it. That was exactly one of the questions I was going to ask: Is there still a place you’ve always wanted to photograph, but haven’t been able to do so yet?

Yes, only the moon. Of course, nothing is as pristine today as it was in the past. In previous decades, access to images and news was not as easy. People had to wait weeks to see a photo report, if they even got access to it at all. The photo had to be developed and printed, the film had to be edited, but today, with the internet and social media, everything is visible in an instant.

People have become image producers and citizen journalists. Once upon a time, being a photographer meant being rare and having access to special opportunities. Today, that uniqueness has disappeared, and at the same time, the costs of becoming a professional photographer have increased significantly. From the price of flights and accommodation to equipment. At that time, we were a few photographers in Iran. Today, however, with a simple mobile phone, anyone can provide a visual narrative of the world around them.

Analog photography was an art; not just pressing a button

In the past, your tools were analog cameras; tools that required a deep understanding of light, composition, and the moment to capture an image. Today, however, with the advancement of technology and the advent of digital cameras, everything has changed drastically. How do you assess this evolution? Has this technical ease also affected the professional spirit of photography?

Absolutely. Analog photography itself was an art. Capturing an image was not just a matter of pressing a button. It was about controlling the light, the composition, choosing the moment, precision, focus, and skill. Today, however, with the advent of digital cameras, many of these aspects are done automatically. The cameras adjust almost everything for the photographer, and it is similar to driving a bus; you just sit behind the wheel and go. This evolution has completely transformed the workspace. High-tech digital cameras and cell phones with their advanced imaging capabilities have made the profession more accessible, but they have also seriously damaged the professionalism and value of the profession.

In the past, for me and others like me, traveling to different parts of the world was part of the job. Curiosity and professional commitment would sometimes lead me to walk from Pakistan to Afghanistan, stay there for three months, develop the photos, and the selection and publication process could take four months. Today, however, magazines and media outlets want images in the moment. Right now, in this very moment.

No one is willing to pay for human photography anymore

Is it possible to say that the speed of information circulation, combined with the decrease in media investment, has put professional photography in a difficult position?

That is exactly the case. The interest of the press in documentary and journalistic photography has decreased significantly, especially in the international arena. The financial dimension has also become very decisive. For example, I proposed a trip to Syria, but the answer I received was “What are you going to bring from there?” That is, there is no interest in investing in human or social issues, unless they are in line with the political or economic interests of the countries. This situation is especially frustrating for those of us who seek human experiences. Today, many trips that were previously easy to do are no longer possible from a financial and professional perspective.

My job is to capture images, not to pass judgment

In this context, with the emergence of artificial intelligence imagery, especially in the documentary and news genres, an important question arises: How do you see the future of honesty in images? Can images still be considered documents?

The answer to this question depends on the audience’s perception. Especially in the fields of film and images. Today we are faced with a reality in which the line between truth and fabrication has become very thin. Today’s world, especially in Europe, is faced with extensive freedom of expression, but this same freedom can easily be abused by partisan, political or ideological tendencies.

In our profession, the principle is impartiality. As a photographer, I never take political positions. I do not judge either side of a conflict. My job is to capture images, not to pass judgment. It is people who should form their own judgments through images.

But the issue of artificial intelligence carries serious risks. Sometimes I see images that are designed so accurately and realistically that it is very difficult to recognize that they are fake. These images are often produced by political actors and have a heavy propaganda dimension. These images may be recognizable to me as a professional, but for the audience they can lead to strong and even violent reactions. Such images easily deepen social divisions, sow seeds of hatred and cause unnecessary provocations.

Artificial Intelligence is useful in portrait retouching, but it can be really dangerous in some places

Some applications of AI, such as portrait retouching or advertising, have improved visual quality. Have you had any experience with this?

Yes, in some areas, such as advertising, AI is very useful. I use a few software myself, especially for portraits, to smooth skin or remove acne to make the face more beautiful. It is acceptable to this extent, but when it comes to more dangerous uses, then the matter becomes serious. It can no longer be said to be just a tool. In the past, when we worked with an analog camera, everything was honest. Film did not allow interference, but when digital came along, along with its advantages, it also opened up ways for fraud. Now, with the advent of AI, we are facing a new stage that we cannot escape from; You have to deal with it, because it has become a part of everyday life.

We once wished for digital; now we see it as a house-breaker

The arrival of digital in the world of photography was both promising and questionable for a generation like yours. How did you view this transition back then?

I remember very well, Mani, we ourselves, wished for digital. A friend of mine always said: If these cameras reach 40 megapixels, I will change my system, but when digital came, it changed everything and really became a house-breaker.

For me, this experience is like carpet weaving. We used to weave carpets by hand, their beauty was natural and alive. Now they weave them by machine, they may have beautiful designs, but that spirit of the carpet weaver is gone. The same thing happened in photography; one by one, film factories closed down and our view of images changed. Technology is a useful tool, but it always depends on who is in the hands of it and how it is used.

Our job is to record reality; AI cannot replace reality

How useful is artificial imagery for you in documentary and news work? Do you see a place for it in your professional work?

No, there is no place for such a thing in my work. These tools may help very slightly, but the basis of our work must remain real. An image that is going to be published in a publication must be a document, not a creation of the mind or an algorithm. I am a journalist and a photographer; my job is to record reality, not to recreate it. You cannot sit at home, listen to the news, write a few lines, and then leave it to an AI to create a picture. This contradicts the spirit of our profession. The value of an image lies in its documentary nature.

An Artificial Intelligence created a picture of me with fire behind me

Have you had any experience of using AI recreationally or experimentally?

Yaghobzadeh: Yes, just for testing, I once wrote my biography and gave it to an AI to create an image based on it. The result was truly bizarre. One of the photos showed me with a beard and flames behind me. In another I was holding a Leica camera, in another a Nikon, one made me look really pretty, and in another a messy, broken image! These photos looked more like a joke than a real representation of a person. For me, who deals with reality and documentation, these are just entertainment and can never replace a real photo.

If I was afraid, I wouldn’t have gone to war at all

You are known for your war photos, and your presence in crises has played a big role in your professional reputation. How have these experiences affected you? How have you managed to control your emotions and still remain a professional photographer in crisis situations?

When I first went to war, I first settled accounts with myself. I told myself: There is death and destruction here, if you are afraid, go home. I had to make my own decisions. In those situations, emotions had to be put aside. When there is a bombardment, there are many dead and wounded, and everyone is on the street, I cannot be a hero and help, especially when there are 10 other people there. My job is to record reality. Recording reality itself is a kind of help.

During these years, I was wounded, I was captured, but none of it affected my spirit. I had prepared myself in advance. I have always said: If your life is going to fall apart by seeing the crimes of man against man, it is better to pack up and leave.

A photographer must be impartial; I cannot judge for the people

When faced with human tragedies, a photographer sometimes finds himself in the position of a judge. How has this been for you?

I have always said that I am not the judge, the people are the judge. I should take pictures, not judge. Just like a doctor who is faced with corpses or horrific accidents every day; he should act and save lives, not be influenced and abandon his work. I also try not to be psychologically affected by everything I see. I do not see nightmares and I do not want to see them. This is a decision I have made with myself from the beginning. The photographer must be prepared to see reality.

If there are 10 people standing, why should I help? My job is to record, not save

Brena: There has always been this criticism that a photographer takes pictures instead of helping. How do you define the line between human duty and professional responsibility?

I have always been asked this question in Iran. Look, if I am alone and no one is around, I will definitely help, but when there are five or six other people standing there, why should I help? If I am in a square like Gaza or Lebanon, a country where I do not speak the language or am not familiar with its medical system, what can I do to help? The end result is that I may make the injured person worse by making the wrong move. In Europe or America, if someone has had an accident, the police will tell you not to touch them, because you may be held legally responsible.

I mean, have you ever been in a scene and put the camera away?

In certain cases, if someone was really alone and the circumstances required it, I have helped, but that is different from a scene where I am a photographer and what I do is bring that person’s voice to the world. As soon as the image is published, it is a kind of help. I was once in Lebanon, during the 33-day war between Israel and Hezbollah. There, I saw people getting emotional, but the question is: why are dozens of people standing around and not going to help? Why is this expected of only photographers? My job is to record that moment. If I don’t take my picture, the world will not know about that event. This recording can sometimes be more effective than a thousand helping hands.

What was one of the most painful and moving scenes you have captured during your career as a war photographer? Tell us about those moments.

During the war in southern Lebanon, I witnessed a very heartbreaking scene. A family of about ten people, after fleeing the conflict zones, had taken refuge in a house on the third floor and had left their belongings there. Suddenly, Israeli planes bombed the building and the entire building collapsed and was destroyed. I made my way to the place and stayed there for two days, but there was really nothing I could do. The only thing I set out to do was to capture these moments, and that was my duty.

One of the most poignant scenes was of a girl who was only ten days old and had come there with her family; they were also killed in the same bombing. A group of people were working with their hands, shovels and picks to dig out the bodies, and I stood behind them and said nothing, because it was not my job to interfere, I just had to record it.

One moment that is still vivid in my memory was when the mother was holding the child in her arms, and all the buildings around them were completely destroyed. I stayed there and took a photo of the mother and the child under the rubble, which was later published in the British newspaper “The Independent”. This photo was so impressive that the British people were deeply affected, and the newspaper sent a special correspondent to investigate the family. I also went with him to southern Lebanon and prepared a detailed report.

By asking friends and acquaintances of the family, we learned that the child had just been born and that his family had first fled southern Lebanon, then died in Beirut. This bitter fate was very sad for me, but at the same time I was happy to be able to record these moments and bring the voice of this family to the world.

Although I am human and my emotions often affect me, I have cried many times in difficult situations, even at funerals and bombings, but I have always tried to overcome my emotions in order to be able to properly fulfill my professional duty.

I was a religious minorities, but I brought the true voice of war to the world

One of the interesting things about your work is that while many Iranian war photographers had an ideological or national perspective, your photographic language was universal. How did you manage to balance the national narrative of the Sacred Defense and the global perspective on the war? What were important points for you in this process?

Many of my colleagues who worked for the domestic press were very partisan and factional. Many aimed only to show the fighters, but I did not get immersed in that atmosphere. I was among the minorities who were well acquainted with Islam, because I had grown up in Iran and most of my friends were Muslim. On the other hand, the national spirit was very important to me; it was my homeland and I wanted to show the reality of war to the world outside of Iran. I saw the war not only from the perspective of the fighters, but from the perspective of all its human dimensions. Ordinary people, refugees, cemeteries, the disabled, prisoners of war. These are all pieces of the war puzzle that, if we don’t put them together, the picture remains incomplete.

Can you tell us more about your perspective on war and its depiction?

War is war, after all. A soldier’s duty is to fight, to be wounded and even to die, but the most important thing is that ordinary people and families lose everything; their lives, their homes, their love and their peace are destroyed. I tried to record these realities, not just the images of warriors in uniform. In the book I recently published, when I was reviewing the photographs, I saw how extensively I worked, not just on the front but everywhere, even where I had to go secretly and secretly to record these images.

This book is a historical document of our IRAN and I hope it will be a lesson for future generations so that they do not repeat the mistakes of the past and prevent war at the cost of the blood and suffering of others.

Do you have any photographs from the war that you have not published for reasons of censorship?

No, I live in France and I have no problem publishing photographs. The truth is that I didn’t take any photos that I wanted to censor. There may be a few that haven’t been published yet, but that’s more due to the choice of subject matter than censorship.

And finally, what about the photos you took during the revolution? Did you have any limitations?

No, I always compare myself to others and I’m really proud of what I did. During the conflicts and the revolution, when the Mujahedin and various groups were fighting in the streets, I would take photos secretly and secretly. If they tell you not to go, it means you have to go and take photos, because this image is part of history.

Interview: Nasim Keshavarz / Borna News Agency