A flight on the border between reality and fiction, suspended in the world of genres

Analysis of short film “DOMESTIC” by Nima Abdolazimi

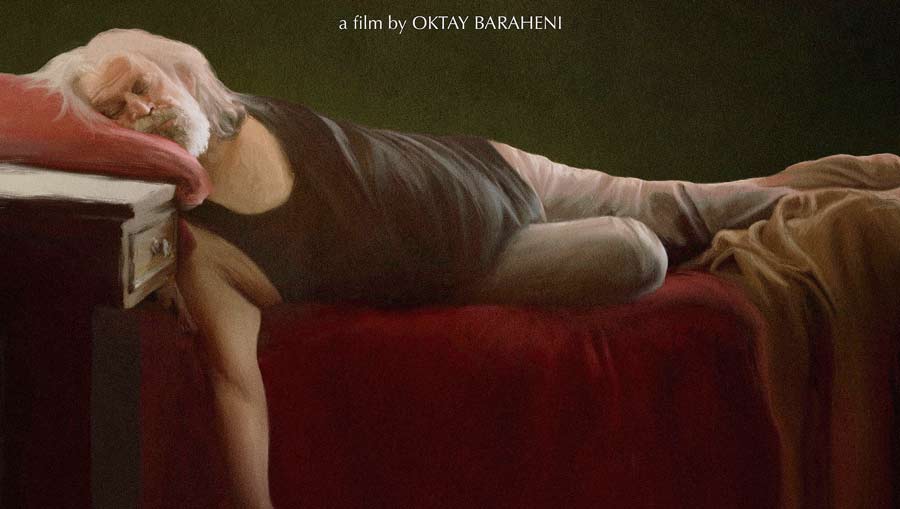

The short film “DOMESTIC,” written by Ako Zand Karimi, Nima Abdol Azimi, Vahid Ahmadi, and directed by Nima Abdol Azimi, is an ambitious work that, by borrowing elements from Kurdish legends and myths, attempts to portray a fantasy narrative of love, sacrifice, and identity in a modern context.

According to Artmag.ir, this work seeks to present a new narrative of the concept of “Magic” in today’s world, where cars, barbecues and city lights are intertwined with supernatural beings and the desires of the human heart. “DOMESTIC” is an attempt to expand the horizons of Iranian short cinema with a different approach to the genres of fantasy and Magical Realism.

I saw this film for the first time at the Sanandaj Film and Photo Week and for the second time at the Rasht National Film Festival. The film had previously made it to the Tehran Short Film Festival and the Fajr Festival. This analysis examines various aspects of the film, including its dramatic function, genre characteristics, narrative coherence and believability.

Summary

The story begins at sunset in the city of Sanandaj. Afshin, a barbecue and coffee shop worker at the foot of Mount Abidar, returns home on his three-wheeled motorbike after finishing his night shift. On a deserted road, he suddenly encounters a large, mysterious horned Whole with a bell. Afshin looks around and puts Whole on the back of his motorbike, takes it to the dark courtyard of his house, cuts off its bell, and puts it aside. The entrance to the house is accompanied by details such as a wedding photo board, a wall clock, and a tape recorder with the song “Bibi Khanom” that convey the man’s loneliness and past, and show his loneliness and emotional background.

After taking a shower, Afshin notices a dazzling light from Whole’s direction, which gradually transforms into a humanoid creature with Whole’s head and a body in a suit. In exchange for Afshin’s good deed (unlocking the bell?!) this magical creature offers to grant Afshin a wish and bring back to life Afshin’s deceased wife. Afshin takes the Magical Whole to the cemetery, and by stirring up dust, it brings Afshin’s wife out of the grave alive. Whole stipulates that Afshin must not touch the woman and must replace her with a body in the grave before sunrise.

Afshin, who does not have the opportunity to kill anyone, first accepts his death and Whole creates a romantic atmosphere with a table, candles and a lantern with a screwdriver so that Afshin can be alone with his wife for the last time. But at the last moment, Afshin is afraid of death and retreats. Whole suggests a third way: Afshin gives his human identity to Whole and transforms into the animal inside him. Afshin accepts and disappears with Whole. At sunrise, Whole, now in the form of a handsome man, comes to the woman with a white rabbit (which symbolizes Afshin’s inner self) and gives the rabbit to her and, in an unexpected twist, offers her wife companionship.

The film ends with a shot of the woman, her newborn child and the rabbit in Afshin’s house, while a black cat is seen in the yard, which could symbolize Whole’s return and the continuation of the story.

1 – Fictional World and Themes: Domesticating What?

“Domestic” attempts to tell a story on the border between reality and fantasy, where magical elements suddenly enter everyday life. The film explores themes such as love, sacrifice, selflessness, and the concept of identity in a Kurdish cultural context. The choice of the city of Sanandaj and references to Kurdish music and language is a commendable attempt to localize a global fantasy idea, however, this localization faces challenges in some details that reduce its coherence.

The name of the film, “Domestic,” is worth pondering. The director mentioned in an interview that the film is about love that domesticates a person. With this explanation, he limits the semantic horizons of the work. Although this phrase can refer to the novel “The Little Prince” and his conversation with the fox, in the narrative context of “Domestic”, we rarely witness “domestication” in its true sense.

Neither the Magical Whole who becomes an ambiguous being at the end, nor Afshin who fears complete sacrifice, nor even the woman who is passive throughout the film, none of them become “Domestic” in the deep sense of the word. If love is a taming force, in this narrative we do not see its effect, but rather a game, a bargain, or even a deception.

The director has also pointed out that his film’s story refers to the concept of ‘Merdazme’ in Kurdish legends, which deals with testing humans. However, if that is the case, ‘taming’ could mean taming the force of the tester through love, or the individual becoming tamed when faced with a difficult test; an event that does not clearly happen in the film. The initial assessment of Afshin by this tester is not very successful or clear, and ultimately, the theme of love in this film is more an excuse for advancing the fantasy plot rather than being deep and believable. The portrayal of Afshin’s love for his wife is limited to a Kurdish song and a few old photographs, which is not enough to convey the depth of such a sacrifice.

2 – Narrative and Dramatic Structure: Contradiction in Magical Laws

“Domestic” lacks a specific and convincing Inciting Incident. Afshin’s encounter with Whole seems more like a random event rather than a point that propels the hero into an inevitable adventure. “Drama is not what happens, but what happens to the characters.” (Robert McKee, Story). This sudden event marks the beginning of the drama and the entry of the magical element into the film’s real world. However, in the development and expansion of this event and the subsequent transformations, the film faces fundamental challenges. While “DOMESTIC” aims to engage the audience right from the start with an unexpected occurrence, the sudden and uncontextualized introduction of Whole into the story and how Afshin reacts to it feels somewhat raw and lacking sufficient foreshadowing.

Afshin takes Whole (one night, on the road, without knowing who its owner is) on his motorbike for no apparent reason. This action, especially considering his profession as a barbecuer, raises the question in the audience’s mind whether Afshin’s intentions were benevolent or whether he intended to kill the missing Whole and roast it for his customers? This ambiguity strikes the first blow to the believability of the story and calls into question the logic of the triggering event. According to Robert McKay’s theories in his book “Story,” the triggering event must properly establish the connection between the ordinary and the extraordinary worlds and justify the main character’s motivations.

The first turning point is Whole’s transformation into a humanoid creature. This moment is a full-fledged entry into fantasy or Magical Realism. The large, stretchy shadow of Whole on the nylon and then its transformation into a human with Whole’s head is a powerful and impressive visual image. This event places Afshin in a position where he must make a decision. But Afshin’s reaction to this development, after the initial fear and astonishment, quickly changes to a state of demand and bargaining. This change of mood seems a bit quick and illogical, especially if we assume that he intended to kill Whole before this happened. This speed in accepting the extraordinary diminishes the depth of the human response.

Whole’s dialogue: “I was afraid you would cut off my head before you took the bell off my neck” immediately contrasts with Whole’s magical power and his ability to resurrect the dead. If he has the power of prophecy, why is he afraid? This logical failure in the magical narrative reduces the believability of the fantasy world. The dialogue “What would you like me to do for you?” also implicitly establishes the connection of this creature with known legends by referring to the “Magic Lamp Demon”.

Afshin does not have any heroic actions and does not undergo any internal transformation even until the end. In the face of a miracle such as his wife’s resurrection, his behavior remains mostly passive and monotonous. Even at the moment when he is about to save his wife and child by dying, he suddenly backs down. This “reversal of the decision” is neither a dramatic twist nor a depth of character; rather, it is a gap in the believability of the characterization. It’s as if the writer and director don’t know what to do with the character they’ve created.

The question also arises as to what positive and benevolent thing Afshin has done for Whole that Whole is willing to fulfill Afshin’s wish? Is simply removing the bell from Whole’s neck enough? While Afshin’s motives cannot be very benevolent either; perhaps Afshin wanted to turn off the bell so that the neighbors wouldn’t notice Whole or so that he could sleep and rest.

Afshin’s decision to revive his wife forms the dramatic core of the story and begins his “hero’s journey.” The choice of the cemetery as the place of return to life symbolizes the struggle between death and life.

Whole’s magical condition: “If you are sure of your desire, put these (Motorcycle Goggles) on your eyes” and the prohibition on touching the resurrected woman establish the rules of this spell. These rules create an element of “suspension” and “knot”. The impossibility of touching the wife is a dramatic tragedy that gives depth to the story. The resurrected woman, dressed and without dirt, symbolizes the return of life and beauty.

The conflict between Afshin and Whole, over his wife, delays the resolution and puts Afshin’s “character arc” to the test. Whole’s insistence on not taking the woman and his offer of “one body for two lives” (referring to the woman’s pregnancy) is a powerful plot twist that sets the climax of the drama. This moment presents the hero with the most difficult choice of his life: sacrificing himself for love. But the information about his wife’s pregnancy is revealed without any prior context and at the last moment, which can create a kind of confusion and a sense of imposition instead of suspense. If this issue had been raised from the beginning as Afshin’s hidden concern, his choice would have been deeper and more believable.

The second turning point is Afshin’s offer to replace his wife in the grave. This moment is the dramatic climax of the film and the greatest test for Afshin, in which he is also afraid and fails. This moment could have been a powerful emotional climax, but the wife’s cold reaction and the lack of depth in Afshin and his wife’s romantic relationship reduce its impact. But the final resolution, namely Afshin’s transformation into a rabbit, is a bit rushed and without sufficient payoff. Why Whole turns to this second option so quickly and why this transformation takes so long is questionable (while other things, such as bringing the woman back to life and preparing a place for Afshin and his wife, happen very quickly and with a single stroke). These developments could have been narrated with more depth, so that they would have moved beyond a mere plot resolution and become a semantic transformation.

Afshin’s refusal to die is the culmination of his inner conflict. His request to “become a slave” and kiss Whole’s foot indicates his failure in the test of sacrifice and ultimately accepting the option of “turning into an animal.” This moment further complicates Afshin’s character. He is neither a flawless hero nor a villain; he is a gray human who surrenders to his weaknesses in the face of death. This complexity of character is a dramatic strength. Whole’s contradictory behavior (indicating that Whole initially said he would do anything he asked for but later had demands) within the rules of the fantasy world undermines the overall believability of the work. If Whole had declared from the beginning that “your freedom is conditional” or “I want something in return for every service,” this lack of commitment would have been more acceptable.

Afshin’s transformation into a white rabbit and Whole’s appearance as a stylish human are the culmination of the changes. This twist has dramatic potential, but it feels artificial due to the lack of context.

The film tries to build suspense, especially in the cemetery scene and based on Whole’s terms and conditions. But the main conflict between Afshin and Whole becomes more of a one-sided deal, rather than a battle of wills, in which Whole always has the upper hand. Whole’s absolute power and the woman’s inaction diminish the intensity of the conflict. Also, the issue of the woman’s empty grave, which Whole had previously emphasized (“she is a trust of the grave and must return to the grave where she belongs” or that another body should fill the grave), is completely forgotten in the end and the grave remains empty without any problem, which is a serious narrative weakness in maintaining the coherence of the story. This contradiction in the magical laws of the Whole damages the believability of the overall narrative and shows that the script has not properly defined the internal logic of its world.

Afshin’s dramatic arc (Character Arc) is also incomplete and unfinished. He transforms from a reclusive man to a rabbit, but this transformation is reduced to a mere physical metamorphosis without showing an inner path, challenges, and difficult choices.

The end of the film, with Afshin transformed into a rabbit and the humanoid Whole asking Afshin’s returned wife for companionship, is a climax that, rather than resolving it, intensifies the ambiguity. Whole’s behavior at the end, immediately after becoming human, in which he asks the woman to go with him, reduces this character from a mysterious magical being to a lustful one. This moment deals the biggest blow to the concept of “Merdazme” and the magical nature of the kal and can create a negative impression of the film. If Whole had looked at the woman with longing and sadness, or even with a look full of desire, and then disappeared, it would have been much more effective than if he had immediately asked for companionship and created the impression that his goal from the beginning was to take over the woman and Afshin’s human identity. This ending creates a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness in the audience and leaves questions and confusion instead of satisfaction.

The film’s open ending, with its depiction of a wife, child, rabbit, and black cat, is mysterious and thought-provoking. But the ending is more vague than profound, due to the lack of coherence in the magical rules and the lack of emotional connection. Open endings in Magical Realism have deep layers of meaning, but in “DOMESTIC,” this ending is more like a festival trick. The audience doesn’t know what the rules of this magical world are and what has turned Whole into a deceptive being. This weakness in the “internal consistency” of the magical world makes it impossible for the audience to play by the rules of the game.

The presence of the Black Cat in the final scene shows an ambiguity in the transformation of Whole into a black cat or the continuation of the magic in the style of the film Jumanji, the cat has always been mysterious in the oral minds of the people of Kurdistan and associated with the world of genies and magic. Although it intends to create a sense of continuity or cycle, it is extremely sudden and without internal logic. If Whole has achieved his human identity, why should he turn back into an animal (cat) and if not, why should he be shown as a black cat? This move is more like an attempt to create a surprise ending than a logical conclusion of the narrative or shows negligence in the construction and ending of the film and the script.

3 – Characterization and Performance: Shadows in the Fog

The characters in “DOMESTIC” remain more like types than deep and multifaceted characters. Afshin, despite an attempt to show his loneliness and isolation, does not reach the necessary depth due to limited dialogues and sometimes contradictory reactions. His sudden fear of death, without a strong background, diminishes the acting’s impact. The Magical Whole character, which has great potential for charm and mystery, is also reduced to an irrational force due to the lack of clarity in his motivations and actions. According to Linda Seeger in Creating Unforgettable Characters (1990), characters must have clear motivations, personality arcs, and emotional depth. DOMESTIC faces serious challenges in terms of characterization that prevent the audience from deeply empathizing with the characters.

Afshin: Afshin is introduced as the hero, but we know little about him. He is a lonely character who is struggling with the loss of his wife, and the actor’s attempt to portray grief is admirable. The song “Bibi Khanom” could have been a sign of his love, but the film does not give it the opportunity to show this love. Afshin’s character arc is not properly formed. On the one hand, he seems to be a devoted lover, and on the other hand, he fears death and retreats at the last moment. This fear and retreat, although human, contradicts the image of a devoted lover who has gone this far. If the film’s intention was to show the complex nature of man and his inability to make absolute sacrifice, it needed to go into more depth in dealing with this hesitation and fear.

In the end, instead of making absolute sacrifice, he accepts the second solution, namely turning into an animal, which could be a kind of denial of human nature, not a full-fledged sacrifice. Afshin’s different Kurdish accent from his wife, Whole, and the people of the region is an executive weakness that can reduce the audience’s (Especially Kurds’) deep connection to the character and create a sense of inauthenticity. Regional details and accent are vital for a work with indigenous roots.

If Afshin’s character had been developed from the beginning in a way that allowed the audience to understand his true motivations in helping Whole, or if a deeper background of his love and suffering had been shown, his sacrifice or even fear at the last moment would have been more believable and effective.

Magical Whole (Merdazme): In Kurdish mythology, “Merdazme” is a magical being with very ancient mythological roots who appears in animal or human form to test the courage, morality, or wisdom of humans and is usually benevolent and has moral tests. In “DOMESTIC”, Magical Whole seems deceptive and his test remains ambiguous, which is a deviation from its mythological origin and adds to the ambiguity of the character rather than strengthening it.

If there had been more cultural context from Kurdish rituals or belief in mountain spirits, Whole would have been closer to the original “Merdazme” and strengthened the believability of the magical character.

In DOMESTIC, Whole is presented as a testing being or antihero, but his motivations and rules are ambiguous. This character is the center of gravity of the film’s fantasy elements, and his presence is visually appealing. But his behavior does not follow a clear internal logic. He is sometimes omnipotent (reviving the dead, creating a scene decorated with a crowbar) and sometimes fearful and limited (fear of being beheaded, or the inability to fully transform into a human being with Whole’s head). The contradiction in his power and goals makes his character a bit ambiguous.

If Merdazme is supposed to be a “Test Man”, what is the purpose of his test of Afshin? Is he trying to test her devotion? If so, Afshin fails the test, but Whole still gives him a saving option (transformation into an animal). This lack of clarity in the purpose of the test and contradicts the concept of a “Test Man” which emphasizes the testing of courage and morality.

As Christopher Vogler points out in The Hero’s Journey, even magical beings must have logic and internal goals.

Finally, Whole, after attaining human identity, quickly praises Afshin’s wife’s beauty and asks for her companionship, which seems unlikely from a magical being with lofty goals and more like temptation or abuse. If we say that he brings this up to test the woman, we do not see the outcome of the test and the reward and the story. This distorts the nature of “Merdazme”, who comes to test humans in Kurdish legends, and reduces him to a merely lustful and opportunistic character.

If the contradictions in Whole’s power and goals were resolved and her behavior was consistent with the internal laws of the magical world she created, this character could have had a much stronger and more meaningful presence in the film.

The Woman (Afshin’s wife): This character is the most passive character in the film. After being resurrected, she has no memory of her past and only asks with a little surprise about her situation in that situation and acts solely as a plot device. Her complete indifference to returning from the dead, seeing the magical creature, and even her husband’s decision to sacrifice himself, and her remaining passive greatly reduces the believability of her character. Her passivity is a major weakness in dramatic terms and prevents the formation of a deep relationship between her and Afshin. We even learn through Whole that Afshin’s wife was pregnant before her death, but we do not know whether the birth of the baby caused her husband’s death or something else. If the woman had more realistic reactions to her return from death and the events surrounding her (e.g., fear, confusion, or even denial), she would have moved beyond being a narrative device and become an active, human character who would have added depth to the story.

4 – Visual Form and Aesthetics: Decorations Without Function

The film’s cinematography, especially in the night scenes and in the cemetery, has a high visual quality. The lighting of lanterns and strings of lamps creates an eerie, magical, and poetic atmosphere, which is one of the film’s strengths. The lighting also makes good use of darkness and urban lights to create a sense of suspense and magic. The use of special effects to transform Whole into a human is acceptable, despite the limitations of short cinema, and helps to make the fantasy element believable.

However, some of these visual elements, instead of enhancing the narrative, become merely decorative and lack a narrative function. For example, the bathtub in Afshin’s house, which is inconsistent with his lifestyle and social class, or the decorated ladder or the candlesticks and unlit candles in the cemetery, which have no narrative function. Instead of creating dramatic reality, these visual choices approach surrealism without internal logic. If these elements had a specific symbolic or narrative function and, with visual details, made the film’s world more unified, the film’s visual impact would be greatly increased.

Whole’s set and costume design: The transformation of Whole into a humanoid creature with the head of Whole is an interesting idea that clearly shows the boundary between reality and fantasy. Whole’s clothes also give this character a special look. However, the contradiction in Whole’s behavior and strength prevents this visual design from leading to any depth of character and ultimately distorts his character.

The question always remains how Whole can talk like a human, stand up, play the violin, wear a suit and vest, but still need Afshin to become a full human? The lanterns in the cemetery scene were added purely for visual beauty, not based on story logic. The set design in the cemetery party scene, with its decorative ladder and artificial lighting, is more of a metaphor than a metaphor, and falls into the trap of Goldorosht’s aesthetics. Whereas in visual symbolism, form should be subordinate to meaning, not vice versa.

Use of Music: The Kurdish music “Bibi Khanom” by Seyyed Ali Asghar Kordestani, in the Afshin’s house scene, helps create a local atmosphere and could be a sign of Afshin’s love for his wife. However, the use of violin by Whole in the cemetery scene, although an attempt to add to the fantasy atmosphere, can seem a bit artificial. A dedicated soundtrack with a fantasy/mythological yet local feel could have greatly helped to deepen the emotions and atmosphere of the film.

Symbols:

• Whole: Can symbolize power, pride, and in Kurdish mythology, the “test man”. Here, its transformation into a human and then taking human nature from Afshin is a symbol of divine power and testing or supernatural forces.

• Bell: Symbol of warning, and perhaps a symbol of “bondage” or “animal nature” that, when untied, opens the path to transformation.

• Pinocchio: (Handmade doll next to the bathtub) Symbol of “transformation” or “truthfulness”. It can mean “transformation” or “wanting to become human”, and perhaps a symbol of “lie” (dishonesty in Afshin’s original intention) or “a journey to become truly human”.

• White Rabbit: Although the director mentions that this animal is “any animal that is inside Afshin”, its connection to Afshin’s characteristics is not properly shown in the film. The rabbit symbol in psychology refers to sexual desires, which, considering Afshin’s sacrifice for his wife, is not properly justified in the film and could lead to ambiguity in characterization. If the film had shown signs of Afshin’s “inner” characteristics (fear, silence, submission, sexuality, etc.) that were related to the rabbit, this symbolism would have been stronger. The presence of the rabbit is only a visual surprise for the end, shallow and rootless.

• Black cat: At the end of the film, it is seen that it could be the same Magical Whole or related to a magical world that has reappeared. This ending could also convey a sense of continuity in the story or the cycle of nature, but it seems a bit dumb due to the lack of internal logic for the successive changes of the Whole and the lack of meaningful connection with the cat throughout the film.

5 – Genre: Wandering between myth, Magical Realism, fantasy and surreal

“DOMESTIC” tries to simultaneously incorporate features of several genres, which can be both its strength and weakness.

• Myth: Myths have deep roots in human culture and history and are usually transmitted orally and from ear to ear. Supernatural elements, gods, extraordinary heroes and extraordinary events play a key role in them. Myths are cultural stories with archetypes (hero, test, mysterious conditions, magical creature) often seek to explain natural phenomena or express the values and beliefs of a society and their main purpose is usually instructive and moral.

“DOMESTIC” is inspired by Kurdish mythological roots, especially the concept of “Merdazme” (the test man). The hero is rewarded for his good intentions (such as saving a creature from danger). But the film faces a challenge in its treatment of the “experiment” and its “moral purpose.” Afshin’s intentions in taking Whole are unclear; did he intend to kill it? It’s more like theft than rescue. There is no saving act (such as rescuing Whole from a trap or danger) that he has performed that would merit such a reward. The lack of a clear moral purpose and a clear outcome of the experiment distances it from the classic structure of a fairy tale and makes the story’s connection to the concept of Merdazme seem weak and flimsy. Even in its treatment of this character, it distances itself from its instructive and moral aspects and turns it into a deceptive creature that is inconsistent with the mythological nature of “Merdazme.” A successful fairy tale film must maintain its mythological roots and present a deeper message than just a magical story. In “DOMESTIC,” this dimension is less emphasized.

If we consider the legend to follow the system of archetypes and mythological narrative, the film lacks the hero’s journey and psychological transformation.

• Magical Realism: Magical Realism introduces elements of the supernatural into a realistic setting, naturally and without the characters being surprised by it.

• Magic is a normal but mysterious part of people’s lives, as if these phenomena were part of everyday reality. “Domestic” has elements of this perspective. (But the film does not succeed in maintaining the “non-surprise” of the characters. Afshin is initially surprised and frightened by the horned Whole, and even the woman is surprised when confronted by Whole and repeatedly asks, “What are we doing here?” These reactions contradict the logic of Magical Realism, in which magical things are considered a normal but mysterious part of life. Also, the sudden and illogical entry of magical elements (such as rabbits and cats) rather than being a natural part of life, instills a sense of surreality. For example, in “Pan’s Labyrinth” by Guillermo del Toro, fantasy and magical elements are intertwined with reality in such a way that the audience lives with the hero in his fantasy world, or in the film “Uncle Bonmey Who Remembers His Past Lives” (2010), no one is surprised by the return of the deceased wife and the spirit of the character’s son, who has become a monkey, and they are very normal with them. They encounter.

In Magical Realism, magic should occur naturally and without further explanation in the real world (as in the works of Márquez). Magic should also be a metaphor for social or psychological issues, but in DOMESTIC, magic is more decorative and the limits of the horned Whole’s power are ambiguous. Why does Whole first say “Say whatever you wish” but then make a condition that the grave must be filled? If he can bring the dead back to life, why can’t he do it unconditionally? And when he makes a condition, why does he forget it again?

In Magical Realism, magic should appear in the context of everyday life, without explanation, and with the characters’ normal reactions. Here, magic is strange, imposed, and questionable. This makes the film closer to symbolic fantasy than to Magical Realism or fairy tale.

The resurrected woman appears faceless, without memory. This could be a sign of a psychological theme or death consciousness; but it continues with absolute inaction and complete indifference. In Magical Realism, characters may not react to magic, but they must have an emotional, mental, or symbolic arc. This woman has none of these.

• Fantasy: The director himself calls the film a fantasy in an interview. Fantasy films often create an imaginary world with its own rules, which can include magical creatures and extraordinary events. The heroes face great challenges and the battle between good and evil is clear.

• “DOMESTIC” is close to the fantasy genre with the presence of the Magical Whole and its unnatural transformations and transformations. But successful fantasy requires creating an internal logic for its magical world. The rules of the Whole’s magic in this film are variable and without a clear rule. Sometimes it is able to revive the dead, sometimes it is afraid of being beheaded, sometimes it needs a long time to change its nature, and sometimes it prepares everything with a single blow. This lack of coherence in the rules of magic reduces the power of the film’s fantasy. If the film were moving towards fantasy, it would need a clearer definition of the rules of magic and the limitations of the Whole, like the limitations of the “magic lamp giant” in legends that determine the number of wishes. Here, the audience does not know why the Whole can do this, what its limitations are, and what its ultimate motivation is? This ambiguity weakens the fantasy of the film and pushes it towards surrealism, where narrative logic is less important. If the laws of transformation and Kal’s powers had been more clearly defined, the film would have been closer to a genuine fantasy.

• Surreal: According to André Breton in the Surrealist Manifesto (1924), surrealism explores the unconscious and irrational images. Elements such as the sudden pond or the black cat are close to surrealism (but the lack of connection to the characters’ unconscious weakens surrealism). These elements are more decorative than meaningful.

Some elements of the film, due to its lack of internal logic and emphasis on unconventional imagery, approach surrealism. (Elements such as the unconventional set design in the cemetery (lanterns that light up spontaneously, an unused ladder), or sudden and gratuitous changes in locations (a pool of water in the cemetery that appears in the morning and after Whole and Afshin’s identity changes), convey a more surreal feeling to the audience. Surrealism usually seeks to disrupt narrative logic and create a sense of the unconscious, but in “DOMESTIC”, these elements seem more like weak set design and a lack of narrative logic than a conscious choice to create a surreal atmosphere.)

“DOMESTIC” attempts to be a combination of these genres, but it does not fit into any of them completely and successfully. The film leans more towards a crude fantasy with elements of fairy tale and surrealism, but the lack of coherence in the rules of magic, the lack of proper character development, and the weakness in maintaining believability prevent it from becoming a strong work in these genres.

“DOMESTIC” hovers between fairy tale, Magical Realism, and fantasy. It has neither the fairy tale coherence of The Trial of Man, nor the believability of Magical Realism, and not fantasy worldbuilding.

It seems that the film’s occasional successes at festivals have been due to the film genre, because fantasy and magical works are rarely made in Iranian short cinema, and this approach makes it noticeable at festivals, but this does not mean complete success in presenting the genre and it is weak in competition with successful fantasy works worldwide.

6. Final Evaluation and Conclusion: Unfinished Potential

“DOMESTIC” is a respectable effort in terms of idea, boldness in combining genres, and utilizing the Kurdish folklore atmosphere. However, this effort has not found the necessary coherence and maturity in the narrative layer, characterization, narrative logic, and cinematic form.

Instead of telling a “story,” the film actually records an “event.” There is no coherent dramatic trajectory that follows the classic principles of drama (plot, climax, first turning point, crisis, second turning point, climax, resolution). The suspense is external, not internal, and the characters follow no definite arc.

Believability in the magical genre depends on the internal coherence and acceptance of the characters’ unusual elements. In “DOMESTIC,” the believability is severely lacking. If more attention had been paid to these details, it could have been a much stronger and more enduring work. For example:

• Afshin’s background: Adding brief flashbacks to Afshin’s life with his wife could have given more emotional depth to his sacrifice and strengthened the audience’s connection to the character.

• Magical Rules: Specifying the rules of Whole’s transformation and powers could have helped make the magical world believable. These rules could have been based on Kurdish mythology, but explained more clearly in the script.

• Whole’s Motivation: If Whole had had more benevolent intentions or his test had a more specific goal (such as measuring true sacrifice or getting rid of loneliness), his character would have been more ambiguous. Instead of a whimsical request at the end, Whole could have parted ways with Afshin or his wife with regret or sorrow after becoming human, which would have been more effective.

• Ending: Replacing the ambiguous ending with a scene where Afshin’s wife (after returning) somehow discovers the rabbit’s identity or establishes an emotional connection with him could have created a more meaningful and less absurd ending. The ending could have shown that true love can survive even in a transformation.

“DOMESTIC” is a work worth pondering, with all its strengths and weaknesses. The film shows that Iranian short cinema, especially in less experienced genres such as fantasy, has great potential to tell local stories with a global approach. But to reach the climax, it needs more attention to detail, narrative coherence, and character development in order to go beyond the boundaries of an attractive idea and become a lasting work.