The dance of identity on the edge of credibility

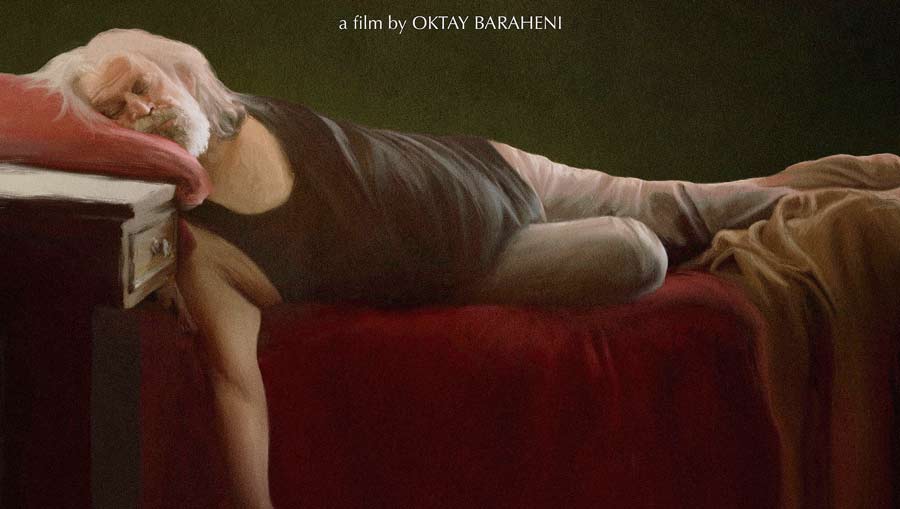

A look at the short film “SON” by Saman Hosseinpour

The short film “SON”, written and directed by Saman Hosseinpour and produced by Philip Rittler and Saman Hosseinpour, is a joint Iranian – Swiss production. It is a bold, minimal, profound, and challenging narrative of a remote and poor village in Kurdistan.

Introduction: Background and synopsis

According to Artmag.ir, the story begins with a lonely old woman looking out of a green wooden window at the alley, waiting for the return of her soldier son (Farhad). The son’s girlfriend (Shirin) also visits their house every day, but there is no news of her Farhad. The mother goes to the barracks and learns that her son has been exempted from the barracks for ten months and has left. Some time later, a woman in a black cloak and veil enters the house and says in a boyish voice: “Hello, mother.” She is the same Farhadi who has changed gender, settled in the city, has become the wife of an elderly man who has become lame, and has now returned to visit her mother. The mother’s encounter with this truth goes from denial (turning on the gas valve) to acceptance (the final hug), but this emotional journey is full of unanswered questions.

The main thesis of this review is to examine how the film “SON” deals with the gap between tradition and modernity and the challenges of identity in a traditional society with a minimal narrative. But the fundamental question is whether this narrative appears believable and logical in the rural and traditional world it depicts?

Given the taboo of gender reassignment in Iran, this article analyzes the film from the perspective of genre and story world, theme and social impact, narrative and conflict, characters, and form and aesthetics, and finally from the perspective of believability, emphasizing the gaps that challenge the audience’s trust.

This film, which has had numerous appearances in a number of student, Kurdish, and international festivals, had not been screened in Iran until recently.

I saw the film at the Sahand Regional Festival in -Tabriz in the spring of 2025, where it won awards. After writing the analysis, I watched the film’s online screening for the second time at a foreign festival and added some details to it.

1. World and Theme: The Silence of an Absent/Native but Isolated Community

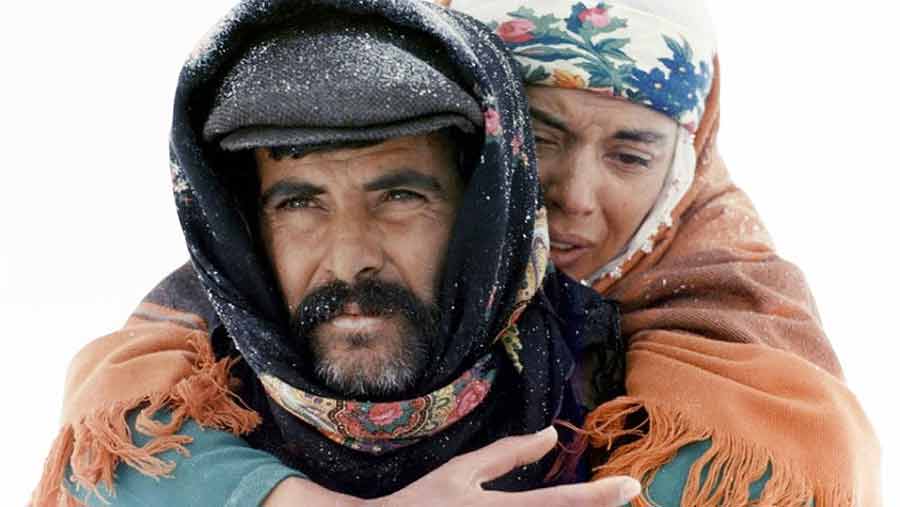

The world of the film “SON” is a world that at first glance seems detailed, tangible, and believable, in which the poverty and simplicity of rural life in Kurdistan becomes a setting for a psychological drama. From the simple and poor atmosphere of the rural house, to the Kurdish clothes and Old Peykan (Old car in Iran), and a small black and white television from the past, everything perfectly conveys a sense of native realism.

The film falls into the social drama genre with a touch of family melodrama, with existential themes, and uses the rules of Iranian neorealism in using real locations and little dialogue, and tries to show the contrast between rural tradition and individual choice.

The main theme of the film is the confrontation between tradition and modernity, which is reflected in the identity conflict between the child and the mother’s expectation. The central theme is the change of sexual identity and its consequences in the heart of a closed society; A subject that has rarely been addressed in Iranian cinema due to its taboo nature. But this thematic boldness, when combined with the logic of the rural world, reaches a sensitive point: is such an event possible in that social and economic context?

The wooden window of the house is a powerful symbol of hope and expectation, while also showing the boundary between the mother’s closed world and the outside world. By choosing a sensitive subject, namely gender reassignment, the film penetrates the lower layers of culture and society, raising questions about acceptance and unconditional maternal love. But its worldview is torn apart because the child’s gender reassignment, without any prior indication of desire or identity crisis, suddenly descends on the narrative as an external and imposed event and lacks the necessary implants.

The Kurdish music “Nishtman” in the minibus (although unrelated to the film’s subject and mostly decorative) conveys a sense of patriotism and attachment to roots, while the main character’s transformation shows a kind of escape from these roots towards a new identity.

The mother is a symbol of a generation that is trapped in old traditions and beliefs, and the child is a representative of a new generation that is rebuilding its body and identity according to its wishes.

The silence that dominates the film has a dramatic function and well embodies the emptiness of the SON. Scenes such as the old woman looking at her son’s photo or the final conversation between the girl/boy and the mother show the attempt to accept and rebuild the relationship.

However, the film does not fully succeed in delving into this theme. Social (such as the pressures of rural society or the consequences of gender reassignment) and psychological (such as the mother’s fear or guilt) subtexts are presented superficially and are not developed. For example, the reaction of the ex-girlfriend, which could have led to a romantic or social subtext, is limited to a fleeting moment.

On the other hand, the choice of the boy’s name (Farhad) and his girlfriend’s name (Shirin), which is based on an old love story and myth, in the form of a large flower, instead of carrying the foundations of love with itself and being on the path of the mountaineer’s beloved, we see that it turns its back on the entire story of this love and eliminates Farhad by choosing another path, and Shirin, with the least reaction to the changed Farhad, turns its back and leaves. In this way, it collapses this myth to show the foundation of love in the modern world without trusting the end of the road.

The film’s worldview, which emphasizes the acceptance of change and the value of family bonds, is humane and universal, but in the context of a traditional village, it seems a bit conservative.

Amid the silence, the stares, the empty alleys, and the closed windows, “SON” is a story of acceptance. Accepting that your child may no longer be the person you imagined him to be, but he is still the person you love, even though he unfortunately shows no signs of loving you.

However, the film fails to delve into these themes:

• Superficial social subtext: The film avoids addressing societal reactions (such as rejection, humiliation, or violence). This silence is either a sign of society’s unrealistic indifference or the filmmaker’s attempt to make the film festival-worthy, in the specific context of Kurdistan, which he largely achieves.

• Hidden but shallow criticism: The references to poverty (old TV, shabby house) and Kurdish identity (traditional dress, singing) could have led to a critique of economic or cultural pressures, but the film limits them to decorative elements.

• Conservative worldview: The emotional ending with the embrace of mother and daughter leads to emotional acceptance, but deeper questions (such as the meaning of identity or the psychological costs of gender reassignment) remain unanswered.

2. Narrative and Conflict: Story Gaps in the Middle

The narrative structure of “SON” is simple and linear. But the hook of the story is established at the very beginning of the film, with the mother waiting for her son. The inciting incident occurs when the mother visits the barracks and discovers (discovers) that her son was exempted from the army ten months earlier. This turning point is the beginning of her search and, ultimately, a confrontation with an unexpected truth.

The main knot is formed with the return of the child in the form of a girl. This event, which is the climax of the conflict, creates the most significant challenge to the film’s believability. By completely ignoring the “process” and focusing solely on the “result,” the film deviates from the fundamental principles of planting and payoff in screenwriting.

The dramatic climax of the film occurs in the scene where the mother turns on the gas valve and tries to end the lives of her daughter and her husband while they are sleeping in the room, due to their refusal to accept this reality. This radical decision shows the depth of the mother’s crisis and internal conflict. But immediately after that, regret and turning off the gas valve are the beginning of the unraveling and, in a vague and hypothetical way, show the mother’s love that prevails over traditional constraints and of course, it may have been based on other reasons as well, because no sign of this friendship and love is seen or heard in the film.

The dramatic arc of the story belongs not only to the main character (the girl) who changes from a boyish identity to a girlish one, but more deeply, it is related to the transformation of the mother’s personality, which goes from denial and anger to acceptance and love, but this change occurs without strong ups and downs and logical arguments.

The lack of suspense and active conflict makes the narrative monotonous. After the gender reveal, the story settles for emotional moments (like the final dialogue or the final embrace) rather than deepening the conflict (like the challenges of the mother’s acceptance or the societal backlash). For example, the moment when the mother turns on the gas to kill her daughter and her husband could have led to a dramatic climax, but that potential is lost with her quick regret. This lack of clear turning points turns the narrative into a visual and emotional sequence.

The main plot point is the conflict between the mother’s expectation and the reality of her son’s changing identity, but this conflict is presented passively. The mother takes no active action to confront or accept. The resolution in the final embrace scene is emotional but lacks dramatic intensity. This emotional ending is not necessarily convincing for any type of audience, some may find it wishful or romantic. Because there is not enough background for this acceptance. Turning points, such as the daughter’s return or her conversation with Shirin, her ex-girlfriend, have the potential to change the course of the story, but they are quickly resolved and slow down the rhythm.

3. Character and Performance: Symbols vs. Humans

The characters in the film “SON” have become symbols to express a big idea rather than being human beings with psychological depth.

The Mother: She is the tragic heroine of the film in a classic drama. Who protects her son’s identity and faces reality. She is the driving force of the narrative and the main source of emotion and conflict. With her son’s return, she is gradually forced to undergo an internal transformation that ultimately leads to his acceptance. A lonely, loyal, and waiting woman. She represents “resistance.” But in the end, she implicitly surrenders. Not out of logic, but out of love or the director’s choice.

Maryam Boubani’s performance as the mother is the main strength of the film; with silences, prolonged gazes, and body language, she well conveys the sense of expectation, despair, and ultimately anger and acceptance.

Her behavior at the barracks (insisting on finding the boy) and her initial reaction to the daughter’s return (silence and confusion) are consistent with the emotional logic of a traditional mother. But the moment she turns on the gas seems unexpected and illogical, due to the lack of psychological background (such as signs of anger or deep despair). Her quick regret also exacerbates this inconsistency; these actions, without psychological context, seem more like a poetic gesture than a maternal or human decision.

Son / Daughter: Despite being at the heart of the drama and in a complex situation, this character (Farhad) does not have sufficient psychological depth. After the gender change, he does not approach the conventional modes either in terms of behavior (girlish excitement and attraction, enthusiasm and excitement of a big change) or in terms of clothing (manto and chador, black veil and gray shirt).

Details such as red nail polish, a gift scarf, or the choice of Kurdish clothing convey a sense of duality between her new identity and her past. But the lack of information about the motivation for the gender change, urban life, or relationship with her husband turns her into an incomplete, lost and nameless character. Her short and embarrassed dialogues, more than being character-building, only have an informative function.

All this happened in a 20-minute film, without a single flashback or explanatory dialogue. The character, from a traditionalist village boy, suddenly transforms into a conservative woman with formal attire and traditional relationships. This is where the film’s credibility collapses. Because the characters have no narrative, no psychological logic.

Husband: This character is simply a dramatic “actor” whose sole function is to complete the process of identity change and marriage. He has no clear characterization, nor are his motives for marrying someone with a complicated past clear.

The role of the husband, with tangible characteristics (lameness, old age, Old Peykan (Old car in Iran), is so brief and without background that he becomes a decorative element. The audience does not know why he has married the girl who has just changed gender, which reduces believability.

Fiancé / Former Lover: Shirin’s daily expectation conveys a sense of loyalty as she visits Farhad’s house and mother every day. She is initially believable, but her simplistic reaction (silence and leaving the scene) is unrealistic, superficial, and lacking in depth. In a traditional village, such an encounter is accompanied by questioning or anger or shame. She too has a symbolic and decorative role rather than a dramatic function. His role as a representative of traditional society is diminished.

The opposing force of the story is not an individual, but the traditions, social beliefs, and expectations of a society in which changing identity is considered taboo. But there is no clear antihero or opposing force, and gender reassignment, which could have acted metaphorically as an opposing force, becomes a situation. The failure to utilize the dramatic potential of rural society as an “antagonistic force” robs the film of its tension, suspense, and ups and downs.

4. Form and Aesthetics: Beauty in the Service of an Imperfect Idea

From the perspective of form, “SON” is a beautiful and impressive work. The cinematography of Robin Engst from Switzerland, with natural light and careful framing, creates a realistic and at the same time poetic atmosphere. The window and the alley, as the main symbols, have a deep meaning.

The editing of Saman Hosseinpour and Zoe Buss, with a slow rhythm, is in harmony with the mood of the film, but this slowness sometimes leads to stagnation. The intelligent use of silence and low music creates a cold and heavy atmosphere that is in harmony with the world of repression and denial.

Music is rarely included, and Kurdish singing in the minibus contributes to the emotional atmosphere of the film. (Although the presence of a stylish young boy in the minibus, who plays an instrument and sings, is not in harmony with the real atmosphere of our villages).

The cinematography and lighting are the main strengths of the work. The frames, with natural light and cool colors (gray, blue, brown), create a realistic and at the same time sad atmosphere. The closed framing emphasizes the mother’s loneliness and isolation; just as the long shots of the road and the minibus show the geographical and emotional distance between the village and the city. The film’s silence and the minimal use of music are consistent with Michel Chevon’s theory in Audio-Vision: silence as a meaningful space. However, the lack of dialogue is exaggerated, and in many places a single sentence could have reduced the confusion of the film’s characters and restored believability in places.

The film’s rhythm, with its fluid and leisurely editing, conveys a sense of the passage of time, but the lack of dramatic climaxes and rhythmic variety creates a monotony. Scenes such as the gas valve opening or the final dialogue could have been more effective in conveying tension with more precise editing and faster cuts. But now it creates a sense of monotony, and the lack of music or sound effects at key moments (such as the mother-daughter confrontation) misses the opportunity to enhance the mood. But, as noted, visual beauty cannot cover narrative weaknesses.

According to Syd Field in his book “The Screenplay,” no matter how beautiful the film is in terms of form, without a solid and believable dramatic foundation, it becomes a decorative work.

5. Plausibility in Cinema: The Foundation of a Dramatic World

The critique of a work of art, especially a film, is not limited to examining its technical and aesthetic elements. At the heart of every deep analysis lies a fundamental question: “Is this story and its world, to me, the audience, believable?” This question is the foundation of every successful drama, and the answer to it can determine the boundary between a forgettable work and an enduring masterpiece. In the following, we will examine the short film “SON” more closely, looking at this key concept.

Before entering into the analysis of the film, it is necessary to address the key concept of “plausibility” (plausibility), not in the sense of “the truthfulness” of the story; the backbone on which every artistic narrative is based.

Believability refers to its “plausibility” within the context of the film’s own worldview, and does not mean that the story must be an exact reflection of reality, but rather to the extent to which the internal logic of the film’s world is coherent and plausible.

Aristotle, in The Poetics, introduces a concept that was later taken up by modern theorists such as David Bordwell: “It is better to use the impossible, which is believable, than the possible, which is unbelievable.” This proposition expresses the essence of believability: a science fiction film about space flight is believable as long as it does not violate the laws of its world. But a realistic drama in which characters make radical decisions without any logical motivation or narrative background, even if they could happen in the real world, will be dramatically implausible because it violates the rules of its own world.

Ever since it was able to frame a dream, cinema has always grappled with a fundamental challenge: believability. The term that Samuel Taylor Coleridge defined as the suspension of disbelief is today the basis of the analysis of any serious work of art. We do not come to the cinema to see the truth, but to believe a lie, provided that the lie is a coherent lie.

Plausibility is divided into two dimensions:

Internal Plausibility: The coherence of the logic governing the film’s world itself. Do the characters act in accordance with their motivations and backgrounds? Are events the logical consequence of causes? This type of plausibility is essential, even in fantasy worlds.

In his book “Story,” Robert McKay emphasizes that any character development must be “planted”; that is, signs of it must be present in advance in the character’s behavior, dialogue, and decisions so that the final transformation does not seem sudden and illogical.

If a magical character suddenly loses his powers for no reason, this defect undermines the film’s internal plausibility. This is what is known as the “suspension of disbelief”; that is, the audience is willing to give up their beliefs about reality in order to enjoy the film, provided that the film maintains its internal logic.

External Plausibility: The film’s connection to the real world and the audience’s expectations. The closer the film is to the realism genre, the more events, behaviors, and details are expected to be consistent with the laws of our world. A film set in a poor village in Kurdistan must be sensitive to the economic, cultural, and social realities of that context.

In an analytical review, the critic’s task is to address not only the narrative logic, but also the emotional and psychological logic of the characters and see whether this logic serves the film’s theme and worldview.

We will now examine the believability of this film from both the perspectives of its proponents and opponents.

As for the film’s critics’ opinion on credibility:

The short film “SON” deals with one of the most difficult and most reflective socio-cultural themes in contemporary Iran and in most countries: gender change in the heart of a traditional society. However, this story, in its narrative structure, is not credible.

In structure, the film seems perfect; but in context, it suffers from a lack of narrative continuity. No basis is provided for the main character’s change: neither internal nor external. The transformation without conflict is more like a trick than a drama.

Serious objection: Instead of showing the transformation, the film only shows the result of the transformation. This means that the most important stage of the drama, namely the character’s path from situation A to situation B, has been omitted.

The world of the story offers no sign of access to the Internet, satellite, or modern information. The poor house, old television, and the lack of a mobile phone show the family’s cultural and economic isolation. In such a context, how does a traditional boy, without access to modern information or consultation with a psychologist, come to the awareness of gender reassignment?

While the character has previously had a girlfriend or lover and has shown no prior signs of identity struggles or different feminine tendencies and attractions, and then he joins the military. This transformation, without any psychological context, seems sudden and unbelievable. Instead of asking us to “believe,” the film simply gives us “news” and expects us to accept it, while the drama should lead us to “believe.”

The gender reassignment process in Iran, according to current laws, requires multiple psychotherapy sessions, psychiatric confirmation to diagnose gender dysphoria, forensic medical examinations, a family court order (according to Article 4, Paragraph 18 of the Family Protection Law of 2012), and exorbitant expenses (surgery, hormone therapy, and recovery period). The film offers no explanation of how these resources are procured or how this process is carried out in the village or military barracks, which undermines the audience’s trust. The obvious contrast with the military context is also evident: it is unlikely that a soldier would be able to initiate and complete this complex and time-consuming path while serving, while for this reason, he is exempt.

At some unknown point in time, he transitioned, settled in the city, got a job, got married, and even decided to adopt a child; with no indication of why or how. These logical gaps pierce the heart of the drama and destroy the external believability that should be consistent with the economic, cultural, and social realities of the Kurdish village.

Irrational Social Isolation: The film portrays the village as completely isolated and devoid of social interaction, with no sign of neighbors, local rituals, or collective reactions to the transition. In Kurdish culture, with its concept of “honor” and collective surveillance, a boy’s transition is likely to be met with gossip, judgment, or even violence. In small, conservative villages, even talking about transitioning is taboo, let alone doing it; any change (even buying a new car) is a topic of conversation among the villagers. But here, no one but the ex-girlfriend reacts to the son’s sudden absence or return as a woman, the world of the film as if it were taking place in a vacuum.

This unreal silence makes the world one-dimensional, as if the film is avoiding facing social realities. This isolation, while contributing to the mother’s sense of loneliness, makes the world unreal. For example, the ex-girlfriend, who visits the house every day, should have at least talked to her family or others about the son’s absence, but the film ignores these implications. The film avoids addressing societal reactions (e.g., humiliation, rejection, or violence) in order to be festival-friendly, and this violates the internal rules of the story world.

Even the girlfriend’s simplistic reaction to the gender transition, shown simply by being upset and leaving the scene, does not fit the emotional logic of an ex-fiancé. This moment could have been made more believable with dialogue or action (such as questioning or crying or anger).

Uncertain urban world: After her gender transition, the girl (the former boy) has started a new life in the city by getting married. But the lack of information about city life, how she was accepted into society, or how the surgery was financed, leaves the world incomplete. The audience does not know how she was accepted into the city, how she met her husband, or how this change occurred in the Iranian cultural context.

The moment of turning on the gas valve and the mother’s quick acceptance: The mother’s decision to turn on the gas valve as a reaction to the boy’s gender transition is illogical, as the film shows no signs of psychological crisis or deep anger in the mother. Robert McKay emphasizes that the character’s actions must stem from internal motivations, but this scene, without psychological background (such as signs of anger or despair), is designed purely for dramatic impact and shock rather than believability. The mother, even after a quiet dinner with her son/daughter’s husband, leaves the two of them in the room and after a while, unable to fall asleep, gets up and enters their room. After some hesitation and deep breathing, she disconnects the gas hose and turns on the tap; but neither of them wakes up with all this noise. Then the mother goes out and sits behind the door in the same room. Her quick regret also seems sudden, without explanation or flashback or…. And we don’t know at all whether she regretted doing this out of fear of explosion, fire and destruction of the house or out of fear of the guilt of murder or out of love for her son and husband?

The film deliberately sacrifices believability for dramatic shock, which is unacceptable in a minimal and realistic drama. Unlike the surreal or comedy genres, where ignoring believability is justifiable, “SON” as a realistic drama must adhere to internal logic.

Adoption: The girl’s reference to adoption, without context, is illogical.

In the Iranian cultural context, such a decision for a newly transgender person requires explanation or context, but the film presents it as a definitive and transient matter. And what is more interesting is that this transient matter becomes the factor of reconciliation with the mother and her embrace of acceptance. Farhad, who has become a girl (and now without a new name and identity), tells the mother, who has turned her back on her, as she leaves, that we have decided to adopt a child from welfare. Although you are upset with me, that boy (who has specified that he is a boy) would like to know his grandmother??!! Now if you are not praying for me, pray for that boy. (Now why a boy? Probably to reproduce the traditional atmosphere again?!). Then she and her husband get on an Old Peykan (Old car in Iran), and leave. After a while, the mother runs outside and enters the main alley and stands in the camera’s view. The boy/girl returns after a while and hugs the mother… (But how did they, who had gotten on the bus and left, immediately notice the mother’s presence in the alley and walk back to the mother and reach her without delay?)

The final hug between mother and daughter, although emotional, is not believable due to the lack of an emotional arc. Without the film showing the stages of this change (such as a deep conversation or a moment of reflection). In the real world, accepting such a change in a traditional mother requires more time and emotional conflict.

Personally, I would have preferred the film to focus on emotional conflicts (such as the deep conversation between mother and daughter) rather than shocking moments (such as the gas valve) to maintain the audience’s trust.

Marrying an old, lame man: This choice contradicts the usual motivations of trans people. Usually, after changing gender, such people seek a free life or a relationship with someone who accepts their new identity, not the reproduction of patriarchal traditions (marrying an older, disabled man). Gender change has become a submission to another form of tradition, instead of a rebellion against it. The film does not provide any social analysis or context in this direction. We do not see the character of the husband to understand why he was chosen, nor do we know anything about the character’s desire for this marriage. This part of the story is more of a visual twist than a psychological or sociological identity. No context, no reason, no depth.

One-dimensional characters and general violation: The boy/girl character is reduced to a “symbol” instead of a complex human being. After her gender transition, she has no feminine beauty, no girlish clothing or behavior, no flirtation, and no new identity. There is no sign of internalizing the new identity in her appearance or behavior. If the character has decided to “live her true self,” there should be signs of this new identity in her behavior, body language, gaze, clothing, or even emotional response. She looks more like a boy dressed in women’s clothing who is silent and indifferent than a woman with a redefined identity. Instead of recreating the identity, the film only shows a superficial change in appearance. The believability of this transformation is severely damaged because the character makes no internal or external effort to live in the new identity. The lack of adherence to internal rules (the traditional world without reaction to change) and the avoidance of social taboos distance the film from a multi-layered drama.

The result of the opponents: Drama without psychological, social and temporal context destroys the character’s credibility. Instead of creating a “gradual transformation”, the script and film of “Boss” only make a “sudden revelation” and are unbelievable.

Analysis of the credibility of the film “Boss” from the perspective of a fan:

Some also try to find another justification for these criticisms and say that the analysis of the film “Boss” requires careful attention to both aspects, because the film challenges the boundary between reality and symbol with an unexpected event. This approach activates the suspension of disbelief and invites the audience to accept the internal logic of the film’s world, even if it does not completely correspond to external reality.

1. Changing identity in a traditional space: a logical challenge or an artistic choice?

In explaining how a boy from a remote and traditional village changes his gender during his military service, and how he reaches such a decision and succeeds in doing so in such an environment, without access to the internet and information, and despite financial poverty, it is said that many filmmakers in arthouse cinema, in order to focus on the core of the drama and avoid falling into the trap of unnecessary explanations, consider part of the story as “given”.

Here, the “boy’s” gender transition is something that the filmmaker presents to us as a definitive fact, without going into the intricate details and process.

The film’s goal is not to narrate the hardships and hardships of this process, but to show the emotional and human consequences of this transformation for the mother and the character herself. The film asks us to “believe” that it happened, so that we can focus on the “why” and the “how.” By ignoring these details, the filmmaker takes the story straight to the climax of the drama, the mother’s confrontation with this truth. This choice allows the film to transform from a social documentary about transsexuality into a deeply emotional drama about acceptance and unconditional love. This approach maintains internal believability because it accepts the transformation as an initial “plant” and focuses on emotional logic.

Answer: Now, if we accept this justification that, based on eliminating assumptions and avoiding documentary-like dumbness and prolonging the story, it has stepped straight to the climax of the drama, shouldn’t it have shown the boy’s desire to change gender in a sentence or a photo or a short flashback so that the audience, along with the mother and lover, don’t fall from the roof of previous perceptions and understand the obvious why?

The assumed and obvious part can be eliminated when the why and how of the main event and the basis for accepting it are ready, not when we try to narrate the story in a clever way and with a single stroke, while the basis for its execution and implementation is questionable and suspicious.

Shouldn’t the mother’s reactions, surprise, anger, concern for society, depression at losing a familiar person, and fear of facing the world of a new person have been shown so that the decision to kill her son/daughter would be believable? Even by accepting the elimination of the process and stages of this gender change, shouldn’t she have prepared us with the necessary short cuts to accept this important change and the mother’s approach and actions? Yes, there was no need to show the stages of this work at all, but she should have prepared the minimum for the audience’s mind to accept it.

2. A boy who became a girl, but did not become “girlish”

Regarding the fact that the character after gender change does not have any stereotypical “girlish appearance” and “feminine characteristics”, they say: At first glance, it may seem like a defect. But if we look deeper into it, this behavior could be a conscious choice and in service of the main theme of the film.

Despite the physical transformation, this character has not forgotten his roots. She grew up in a traditional, rural culture and, even with a radical transformation, has not changed her identity symbols. She does not become a “modern city girl,” but rather a “country girl” who still maintains her cultural simplicity and modesty. The red nail polish and a little matte are just small signs of this inner change and discovery of her feminine identity that she carries out in her private life, in a way a tribute to her inner feelings, but in front of society and her mother, she maintains a traditional and modest dress.

This internal contradiction makes the story more complex and the character more believable. She is not fighting her traditional identity, but rather trying to blend and integrate her new identity with it. She transforms from a “traditional boy” to a “traditional girl,” which is itself a deeper message about the conflict between individual freedom and the preservation of cultural identity. The avoidance of “stereotypical femininity” may be intentional; an attempt to portray a “quiet, non-dramatic girlhood” that enhances emotional believability and draws inspiration from the external logic of traditional society.

But the answer to this part is also given in the above material. Although we may say that her intention was this or that, there is no evidence to support this interpretation. Rather, her not informing her mother for more than ten months and her marriage in the city without her parents’ permission and knowledge refutes this hypothesis and justification, stating that she has transformed from a traditional, rural boy into a modest, traditional, rural girl, and that she has not committed a serious breach of the norm. On the other hand, when she goes to her mother’s house with her husband, contrary to the traditional, rural world, they sleep together in a separate room with her husband, which also contradicts the traditional rural girl.

Shirin can be a symbol of this rural girl who is neither wearing a veil nor a black veil in the film. She is wearing Kurdish clothing and has a more girlish look and part of her hair is visible, but Farhad, who has become a girl, has become more traditional than a traditional girl and has abnormal behavior, and in fact, she is extreme and unfamiliar with the dress and color of village girls. It is as if, by changing her gender, she has become a representative of the dominant ideology, and with her cloak, veil, and black veil, she highlights this opposing ideology, not the lives of traditional village girls.

3. Marrying an Old, Lame Man: Choice or Inevitability?

One of the most challenging parts of the film is the main character’s marriage to an old, lame, and lame man. At first glance, this marriage seems to contradict the spirit of “rebellion” and “change” that lies in the decision to change gender. If she has made such a decision to break free from traditions and find her true identity, why does she submit to the tradition of marrying an unsuitable, older man? In response to these questions, fans say that this choice can be examined from several perspectives:

The symbolism of the choice: This marriage can be a symbol of the “deal” and “compromise” that people who are rejected by society are forced to make. After changing gender, this character will most likely not be accepted in her traditional society, and perhaps her only refuge will be someone who is physically and visually outside the norms of society. This choice may not be out of love, but out of a need to be accepted and find refuge in an alien world. Perhaps the film wants to show that even among trans people, social pressure and class constraints can lead one from rebellion to isolation and submission. The choice of an older spouse may symbolize the inevitable marriage to establish a new status, not love.

Avoiding stereotypes: With this choice, the filmmaker avoids falling into the trap of conventional stereotypes about gender reassignment (which are usually associated with good looks and marrying someone attractive). In doing so, she shifts the focus from aesthetics to the harsh truth of social reality. Marrying this man is not a romantic choice, but a realistic and bitter one that shows that even after finding one’s true identity, the path to a normal life in society is not always easy.

Hidden messages: Perhaps this marriage is a subtle criticism of a society that sees women as commodities to be married to wealthier and older men. With this marriage, the main character, on the one hand, achieves her identity, but on the other hand, as a woman, she is exposed to the same limitations and problems as traditional women. This could be a complex and bitter ending that shows that gender reassignment is not the end of the struggle, but the beginning of another. The film’s approach to this point strengthens internal believability with symbolism and avoids unnecessary explanations.

But in response, it must be said: Farhad did not marry in his village nor under pressure from his parents or the people of the village. He did not return to his village after his gender reassignment and no one knows about him. He took this path alone and settled in the city, found a job and got married, so his marriage was a matter of choice, not under pressure from culture and tradition, nor to show the continuation of the trans struggle. It should also be said that no cultivation has been done for all these possibilities to make us accept them. Where in the film is the least struggle shown?

Finally, we can say: The short film “SON”, from the point of view of these fans, has broken away from tradition and has not reached modernity. It can also be said that as an exception, there may be those for whom these possibilities are true, but as it was said: We do not come to the cinema to see the truth, but we come to believe a lie, provided that that lie is a coherent lie.

Final Assessment: Bold Theme vs. Weak Narrative

The film “SON” is a work about a noisy taboo, along with visual beauty, the brilliant performance of the actress playing the mother, and its emotional ending, but the film has serious gaps in terms of believability. The lack of narrative implantation for the child’s personality development, the complete elimination of the gender transition process, and the failure to show the reaction of society are weaknesses that damage the film’s internal and external logic. Instead of showing us the necessary reasons and context, the film only shows the “destination,” which reduces it from a deep psychological drama to a “news story.”

“SON” could have become a more coherent and lasting work by adding short flashbacks, showing internal signs of the past, or even limited encounters with society. The film ultimately leaves us with a fundamental question about the nature of drama: Can a story, even if it is logically flawed, capture the audience’s heart with its emotional power and remain in their minds?

The film, with its gender transition theme, treads new and less-tried territory in Iranian cinema. This narrative boldness is both risky in relation to the indigenous culture of Kurdistan, requiring greater social and narrative depth, and festival-friendly outside of Iran.

Ultimately, a film that wants to narrate an identity crisis must first introduce its world to the audience in order to ask them to believe in the identity of its character. But this film has not created a credible platform for either the supporters or the opponents; it remains in the middle of the road and must be said to be like a tree that has branches but no roots; it has a shadow but no trunk.

And about cinema, they have said that “it is better to use something impossible that is believable than something possible that is unbelievable.”

![]() Watch online: Farhangfilmfest.org/video/son

Watch online: Farhangfilmfest.org/video/son