The identity and language of Kurdish Cinema

Kurdish Cinema, as the largest example of a Transnational and Stateless cinema, is an identity-based movement that has formed across Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and The Diaspora.

This article aims to define the identity independence of Kurdish Cinema, first explaining the characteristics of an independent national cinema. Then, it shows how this cinema has created a distinctive poetic, metaphorical and symbolic language. The conclusion of the article, while emphasizing the complete identity and stylistic independence of Kurdish Cinema, discusses its continued dependence on dominant regional cinemas in the field of industry and global distribution.

1. Anatomy of an Independent Cinema: Criteria for Identity

What is Cinematic Identity?

Cinema is a mirror that reflects the culture, history, and soul of a nation; a visual language that not only tells a story, but also redefines and sometimes brings collective identity to life. But what makes a cinema “national” or “identity”?

To answer this question, we must examine multifaceted criteria that encompass a combination of culture, history, aesthetics, and industry. These criteria help us distinguish the identity of a cinema from others, whether it is Hollywood cinema, French cinema, or an emerging movement like Kurdish Cinema. The cultural and identity roots of any cinema with identity grow from the soil of the culture and history of a nation.

To assess the independence and identity of a cinematic movement (such as American, British, Latin, French, Iranian, Kurdistan, etc.), one must pay attention to a set of multiple characteristics beyond mere geography or language of film production. A national or independent cinema is a combination of cultural, historical, aesthetic, and industrial factors that crystallize in the final signature of the work.

1.1. Cultural and Identity Context

• Language and Dialect: The main language of films is not only a means of communication, but also the complete carrier of the culture, folklore, humor, oral literature and the specific way of expression of that nation. This language defines cultural boundaries.

• Traditions and Customs: The reflection of the traditions, rituals, legends and indigenous cultural values of the region in the content of the films. (such as traditional dance and music in Indian cinema).

• Local Topics: Focus on social, political and human concerns that are rooted in the specific conditions of that society. (such as family issues).

1.2. Aesthetic Style

• Visual Characteristics: A unique visual signature, such as minimal framing (Japanese cinema, such as the works of Ozu), rapid cuts (French New Wave), or distinctive use of color and light.

• Narration: A style of storytelling, ranging from linear, hero-driven narrative (Hollywood) to magical realism and multi-layered narratives (Latin American cinema).

• Music and Sound: The distinctive use of soundtracks (traditional or indigenous) or meaningful silences and ambient sounds to convey emotion.

1.3. Historical and Political Context

• National History: Reflections on significant historical experiences such as war, colonization, or revolution that shape the collective memory of a nation. (e.g., guilt and reconstruction in post-World War II German cinema).

• Politics and Censorship: The direct influence of government regulations and restrictions on the form and content of films, often resulting in the creation of metaphorical and symbolic language.

1.4. Industry and Economy

• Production Structure: The existence of an independent industry, including studios, local funding, and an organized mechanism for production and distribution. American cinema is defined by Hollywood and its studio system, while Cuban cinema is more state-owned and ideological.

• Audience and Export: Production for a domestic audience and then the ability to export globally to represent that cinema as representative of its nation. For example, Bollywood cinema was first designed for Indians, but is now global.

1.5. Key Figures and Artistic Movements

• Iconic Directors: The presence of great directors with a distinct style creates identity. For example, Italian cinema is known for neorealism (Rossolini, Visconti), or Iranian cinema for Abbas Kiarostami and Asghar Farhadi.

• Cinematic movements: Specific waves such as the French New Wave or the German New Cinema give cinema an identity.

1.6. Interaction with the world

• Influence and influence: A national cinema is both influenced by and influences world cinema. For example, Japanese cinema was influenced by Hollywood, but directors such as Kurosawa also transformed Hollywood.

However, it should be noted that cinematic identity is not always constant and changes with time. For example, Iranian cinema before the revolution is different from its after, but both are part of its identity. Or American cinema, which has reached from Westerns to modern blockbusters.

A nation’s cinema gains an independent identity when it is rooted in its culture and history, creates a distinctive visual or narrative style, and is able to sustain itself industrially.

2. Kurdish Cinema: Stateless Cinema

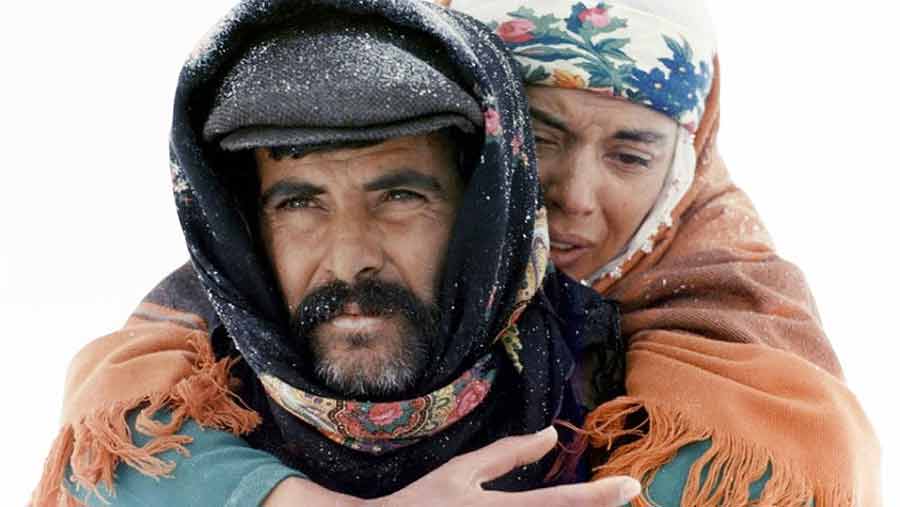

Kurdish Cinema, with a population of between 30 and 45 million people in the Middle East and spanning five countries (Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Armenia), is a prime example of a stateless cinema. In the absence of a nation-state and facing the challenges of language, identity, and cultural repression, cinema has become a key tool for preserving collective memory, transmitting cultural heritage, and resisting silencing.

In Kurdish Cinema, identity is not an optional subject, but rather its most important element and reason for survival. Filmmakers have strived to portray an identity that is at odds with the official and stereotypical narratives of the host states.

2.1. History: The Roots of a Resilient Voice

Unlike national cinemas with their old industrial infrastructure, Kurdish Cinema developed in the absence of state support and dates back to the 1920s:

• Historical Origins in Armenia: The silent film Zare (1926), directed by Armenian Hamo Bek Nazarian, is considered the first feature-length Kurdish Film in Soviet Armenia. The film depicts the love story of a Kurdish-Yezidi couple and depicts Kurdish Rituals and dress, demonstrating the historical bond between the two nations.

The film Krder-Ezidner (1933), directed by Amasi Martirosyan, also depicted the life of the Yezidi Kurds and demonstrated the historical bond between the Kurds and Armenians as oppressed peoples.

• Identity-based pioneers: In Turkey, Kurdish-Zaza filmmaker Yilmaz Günay, with works such as “Yol” (1982) (winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes), written and directed by Günay in prison, although forced to use the Turkish language, brought Kurdish Identity from the margins to the center of global narratives by incorporating costumes, folk music, and a focus on the poverty, oppression, and rural life of the Kurds.

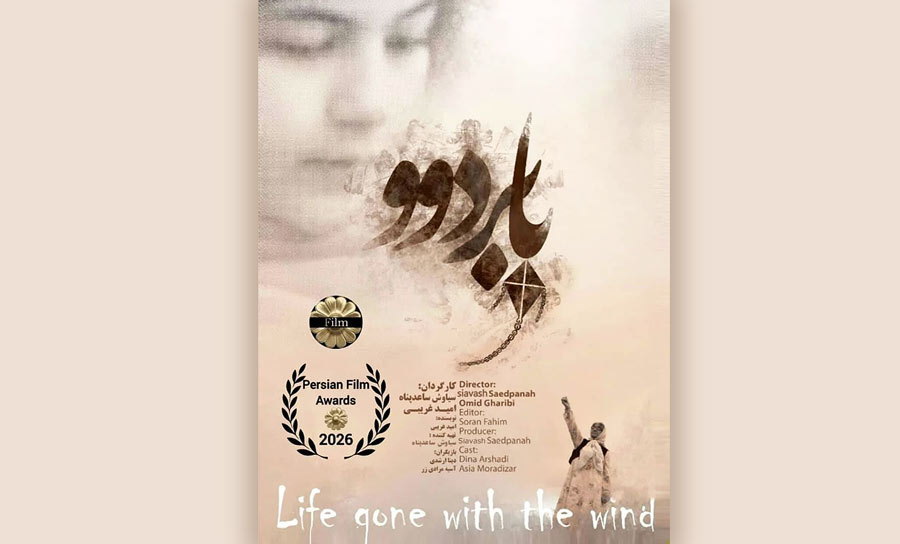

• The rise of the Kurdish language: In Iran, Bahman Ghobadi paved the way for direct representation of the Kurdish Language and identity with “A Time for Drunken Horses” (2000) (winner of the Golden Camera at Cannes), the first feature film in the Kurdish Language. In this film, he narrates the lives of children smuggled on the Iran-Iraq border in poetic and realistic language.

• In Iraq, after the fall of Saddam in 2003, Kurdish Cinema saw a significant growth with works such as Bekas (2012) directed by Karzan Qadir and Memories on Stone (2014) directed by Shaukat Amin Korki.

In Syria, severe Baathist restrictions and civil war limited production to short, underground documentaries such as Kobani (2022), directed by Özlem Arizba, which depicts Kurdish Women’s resistance to ISIS.

In the diaspora, filmmakers such as Huner Saleem’s Vodka Lemon (2003) in France chronicled the lives of Armenian Kurds in the post-Soviet era.

3. Unique Characteristics of Kurdish Cinema

Kurdish Cinema has established its distinctive signature in the world of cinema by using the three components (cultural, stylistic and political) introduced in the first section.

3.1. Language: Cultural Carrier and Flag of Resistance

The Kurdish Language, with its diverse dialects (Kurmanji, Sorani, Hawrami, Kalhori, etc.), is the pillar of the identity of Kurdish Cinema.

• Struggle for Existence: In countries where the Kurdish Language has been banned or restricted (such as Turkey until 1991), producing films in the mother tongue is considered a political and cultural-political statement in the fight to preserve existence. This language carries folklore, humor and oral literature (especially maqams and songs) and transmits the specific way of expression of a nation. This is particularly evident in Kurdish Documentary cinema, where the camera goes among the people to record first-hand and unmediated accounts of everyday life, suffering and aspirations in Kurdish.

• Multilingualism and border identity: Kurdish Cinema is inherently a border cinema. Geographical dispersion has led to the creation of multilingual narratives (Kurdish, Turkish, Persian, Arabic). This multilingualism, in contrast to the derogatory “dialects” in the dominant regional cinemas, reveals the depth of the Kurds’ lived experience in interaction with the “other” (such as Hunar Salim’s “Kilometer Zero”).

For example, Ghobadi emphasizes in an interview with Cinéaste magazine (2005) that he makes his films in Kurdish in order to speak directly to Kurdish Audiences, because “Kurds have lived for years without Kurdish Films or language.” In Half Moon (2006), Kurdish music and dialogue whisper the longings of a dispersed nation, while in Marooned in Iraq (2002), traditional Kurdish Music brings the film to life.

This use of the Kurdish Language, along with folklore, proverbs, and rituals such as the Halperki (group dance), not only reinforces cultural authenticity but also resists negative stereotypes in dominant regional cinema (such as the portrayal of Kurds as smugglers or rebels in Iranian or Turkish cinema).

3.2. Aesthetics of Censorship

The greatest achievement of Kurdish Cinema is the creation of a poetic, symbolic and metaphorical language.

• A gypsy from the ashes of censorship: In a situation where the direct display of identity-seeking demands is prohibited, Kurdish Filmmakers have been forced to turn to a symbolic, poetic and metaphorical language. This restriction, in a surprising turn, has turned into the creation of a deep, imaginative and international style (such as the works of Ghobadi and “Monuments on Stone” by Shaukat Amin Korki).

• Key symbols:

• Mountains: not only a visual backdrop, but also a symbol of the Kurdish Nation’s resilience, cultural separation, refuge and elusive freedom.

• Children: a symbol of lost innocence, victims of historical disasters, and an unbreakable hope for the future (such as the smuggled children in “A Time for Drunken Horses”).

• Silence and landscapes: The use of long silences, long shots, and natural sounds (wind, snow) to express unspeakable suffering, loneliness, and hidden hope in the absence of direct dialogue (such as Jamil Rostami’s “Jani Gal”).

• Cultural rituals: The depiction of local rituals such as Halparki (group dances), traditional music, and Kurdish dress are tools for conveying a deep sense of cultural belonging, collective joy, and cultural resistance to assimilation.

• Social realism: Unlike Iranian cinema, which sometimes tends toward philosophy and abstraction, Kurdish Cinema focuses on the harsh realities of life in border areas, poverty, exile, and the struggle for survival.

3.3. Central themes and distinctions from regional cinema

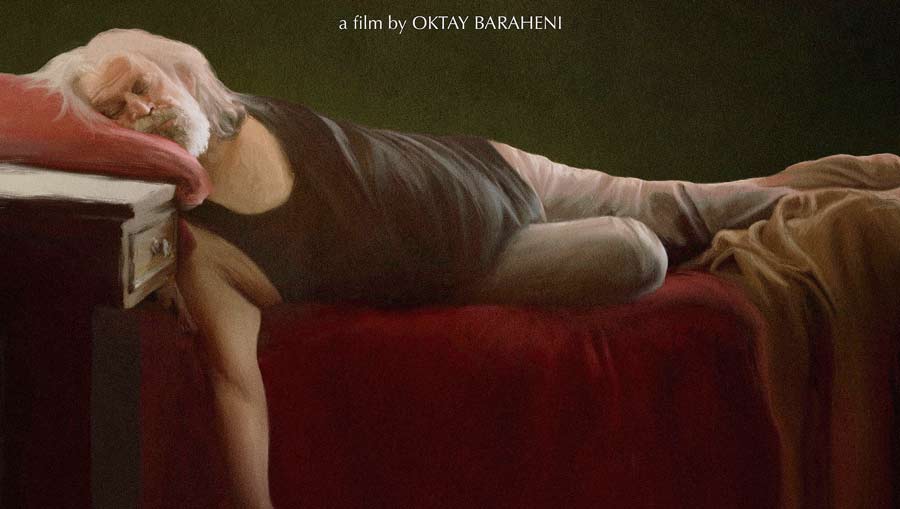

The main themes of Kurdish Cinema revolve around war, displacement, border poverty, the position of women and children in crisis situations, and the constant search for land and identity, and for this reason, it is mainly a catastrophe cinema, in which narratives are shaped around historical suffering (such as genocides, Anfal, and chemical bombings) and ongoing political conflicts. At the same time, this cinema focuses on ordinary people and the lower classes of society who resist greater forces with simplicity, courage, and patience.

(For further reading, you can refer to the book: Catastrophe Narrative in Kurdish Cinema ( گێرانیوەی کارسات لی سینیمای کوردیدا ) by Amir Gholami and Amjad Gholami).

| Distinction | Kurdish Cinema | Dominant regional cinema (Iranian, Turkish, Arabic) |

| The Centrality of Identity | Emphasizing ethnic identity, mother tongue, and resistance to Assimilation. Like Zer (2017), directed by Kazem Oz, In Search of a Song from a Grandmother returns to and highlights her Kurdish History and identity. | Focus on national identity (Persian, Turkish, Arabic) and often portraying Kurds in marginalized stereotypes. Like Nasser Taghvai‘s film Sadegh Korde |

| Visual Style | Forced metaphorical language, harsh realism in borderlands, symbolism of mountains and children. Like Ghobadi’s films and Karzan Ghader’s film Bix | A tendency towards philosophy and abstraction (Iran), modernization (Türkiye), or urban/religious dramas (Arab). |

| Language | Using multilingualism to portray the reality of borderland; using the Kurdish Language as a political statement. Like the film Zero Kilometer by Honar Salim | Often using accents or completely eliminating minority languages. Such as the film Eagles by Samuel Khachikian or The Epic of Schiller Valley by Ahmad Hassani Moghadam or the series Noon Kh |

3.4. Production Structure: From Diaspora to Individual Productions

From an organizational perspective, Kurdish Cinema does not have an organized industry. It relies on low-budget, individual, and independent productions, mainly short films made with individual funds, diaspora support, or small international partnerships. Due to their lower cost, short films are thriving in Iraqi Kurdistan and Iran. Censorship in Turkey and Syria limits domestic distribution, and many films reach audiences only through foreign festivals or digital platforms such as YouTube.

• The role of The Diaspora: The widespread dispersion of Kurds in Europe, the United States, and Canada has created a significant diaspora. This diaspora, which sociologists call the “new friend of the stateless nation,” plays a vital role in intellectual production, financing, and cultural lobbying (such as the Kurdish Film festivals in New York and London, etc.). These festivals have become a platform for Kurdish Films from all over Kurdistan and the world and are very effective in maintaining cultural resilience.

• Resistance Economy: Due to lower costs, short films and documentaries thrive and are often made with basic equipment. This lack of government infrastructure, while preventing them from becoming “body cinema,” has given filmmakers more freedom and boldness to express their personal and political concerns.

4. Conclusion: Identity independence in industrial dependence

Finally, Kurdish Cinema is an original, resilient and productive movement. The answer to the main question of the article requires a distinction between two areas:

1. Identity and stylistic independence: Yes

Kurdish Cinema has achieved a distinct identity in terms of culture, language, thematic and aesthetics. The poetic metaphorical language, the focus on repressed identity, the mountain as a symbol of resistance, and multilingual border narratives are the signatures that distinguish this cinema from the national cinemas of the region.

This cinema is a poetic school that arose from tragedies and, relying on its culture, became a song for a nation that stood against silence.

2. Industrial independence and distribution: No

Kurdish Cinema is still young and dependent in terms of industry and global distribution. Films made by Kurdish Directors are often introduced in international circles as “Iranian films” or “Turkish films”. The lack of local studios, large budgets, and wide distribution weaken the independent identity of Kurdish Cinema on an economic and marketing level and place it in the shadow of larger cinemas.

The future of Kurdish Cinema depends on strengthening diaspora infrastructure, transnational solidarity between Kurdish Filmmakers in five geographies, and continuous efforts to introduce itself as a completely independent cinematic movement on the global stage.

Sources:

Zare (film). Wikipedia entry and historical filmography sources

• Sina, Khosrow. (2017). “Identity is the most important element of Kurdish Cinema”. Mehr News Agency

• Tehaminijad, Mohammad. (2009). Iranian cinema and the issue of identity. Negah Publishing House, Tehran

1. Alasti, Ahmad, and Shafiei, Maryam. (2016). “Ethnic Cinema in Iran: Challenges of Identity and Censorship”. Jahan Cinema, No. 123

2. Aref, Mohammad. (2018). “سینهمای کوردی و کێشهکانی: لهژێر سانسۆردا”. Hawlati, special issue of Kurdish Cinema, Sulaymaniyah

3. Noori, Delshad. (2020). سینهمای کوردی له روژاوادا: ههوڵ بۆ سهربخهوهیی. Kurdistan Printing House, Erbil