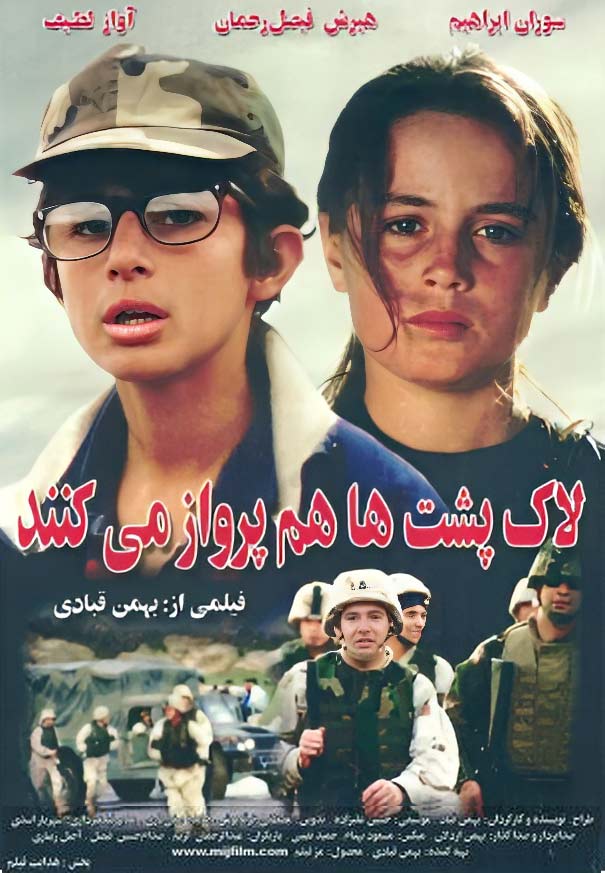

The film Turtles Can Fly (Bahman Ghobadi, 2004) has been the focus of attention from critics and audiences since its release, and has been both praised and criticized for its depth and multi-layeredness.

According to Artmag.ir, the work is a masterful blend of art, literature, myth, symbol, humor, and insight that blends Kurdish nationalism with an internationalist outlook. The film can be examined from various perspectives, but this note focuses on two main axes: mythology and social and cultural symbolism, both of which showcase the identity and suffering of Kurdistan in the cinematic frame. The aim of this analysis is to deepen the audience’s understanding of Ghobadi’s masterpiece and to illuminate its hidden layers.

Mythology: Water, Fire, and Invisibility at Its Peak

Mythology runs through the film like living veins in Turtles Can Fly. Water, fire, and mountains, symbols of purity in Zoroastrianism and earlier in Mithraism, are central to the work. These elements are associated with goddesses such as Ardavirasur (Anahita, goddess of water), Ater (Azar, god of fire), and Mithra (Mithra, god of the sun and covenant). In these rituals, temples of water, fire, and the sun were built on the tops of mountains, where the earth reached the sky. Agrin, the suffering girl in the film, is the embodiment of these three elements, and her name (Agrin, meaning fiery) itself is a testament to this mythological connection.

Agrin’s first appearance is accompanied by the reflection of her image in the water of a spring, as if Anahita had manifested in her. The film ends with him at the top of the mountain, where his disappearance, which appears to be a fall, occurs. Except for his shoes, which are neatly stacked, no trace of him remains.

This scene is reminiscent of the thirty-bird-like movements of Kaykhosro, the Kiyan king in the Shahnameh, who, before disappearing into the snow and fog of the mountains, divided his possessions among the heroes and made his way to the sky. By deliberately not showing a body, a piece of clothing, or the depth of the valley, and by emphasizing the neat shoes, Ghobadi conveys the concept of Agrin’s pure flight: she did not fall, but disappeared at the top. This is the flight of the turtle that the film refers to: a sad and ashamed turtle with its head in its shell and the only way to escape is by flying.

Agrin had previously chosen water and fire for her death. She asks for the Red Fish of the Spring to heal the eyes of Riga, her unwanted child; a fish that in ancient Iranian mythology symbolizes life and fertility.

This choice of fire over water, which to the uninformed audience appears to be due to the girl’s fear of death, is in fact an attempt to combine the tenderness and purity of Anahita, the goddess of water, childbirth, and fertility, with the cleansing power of fire (Ater). Agrin, stained by the Baathist rape, wants to drown in water and burn in fire to cleanse herself of shame and sin. But the call of Riga, the innocent child, brings her back. Finally, A,o chooses the peak of the mountain, a mythical place of worship, to disappear in order to be freed from the shame of rape and the sorrow of killing her child and to reach the sky, which is associated with Ahura Mazda. Myths say that to reach God, one must stand on high mountains and reach the sky; Agrin does so and reaches.

Riga, the child in the film, is a reflection of the myth of Sohrab, Rostam’s son. Sohrab, who was of Rostam’s Mithraic lineage and related to the Ahramanian Turanians on his mother’s side, was killed by his father to remove his contamination from Rostam. Riga, too, is of Kurdish and pure descent from a Baathist and impure father. She is sacrificed by the hands of her mother, who is a symbol of tenderness and kindness and a descendant of Anahita. Riga’s death, in which she drowns in the water with a stone tied to her foot, raises questions: why this?

Why did Agrin’s attempts to free her in barbed wire, in the fog, or by tying her to a tree (which itself has an ancient myth of sacrifice) fail? Why does Agrin, after drowning Riga, move away from the spring to disappear into the mountains?

The answer lies in Agrin’s myth and experience. Mother and child should not die together because the mother is not in love with her twin child, because Agrin does not consider herself the same as Riga. She remembers the night when the Baathists attacked her by a pond and stained her skirt in the water. So the creature of that filthy night must return to the same water, with bound legs and bound to death, to show that whoever is twinned with aggression and oppression, even if he is from the heart of Kurdistan, will be driven out and destroyed.

Riga’s bulging eyes also open another layer of the myth. In Zoroastrian beliefs, bastard children were sometimes distinguished by signs such as bulging eyes. Qobadi, however, takes this symbol further: he shows the enemies of Kurdistan as left-eyed, unable to look at this pure land with friendship and honesty. Whoever has such a look is doomed to destruction.

Symbolism: From Bitter Humor to Social Criticism

The symbolism in Turtles Can Fly is one of its outstanding strengths, which explores social and cultural layers by using exaggeration, irony, metaphor, and biting humor. This humor is sometimes expressed in Shirko’s slaps, sometimes in the children’s incorrect answers to the teacher’s math question in the presence of the satellite, and sometimes in the normalization of satellite viewing: men who initially flinch at the embarrassing images, but then stare at the screen with relief.

These moments, which also contain psychological traces of agrarian conflict, social prestige, or the war over prestige, provide a platform for deep analysis, although this note leaves them to other analyses and focuses on the symbols.

Antennas and satellite dishes, the early symbols of the communications age, occupy a large part of the film. The opening scene, which shows the camp struggling to install antennas, speaks of the people’s desire to participate in the modern world. But this effort fails and the antennas return to the people like a heavy burden. The solution is shown by a teenager who seems to symbolize the conflict and difference between the two Kurdish generations.

Cock Satellite, a teenager whose name carries the communications age, is the changemaker of this land. With a strange transaction – a combination of barter (the exchange of 15 radios, a symbol of tradition) and cash (500 dinars) to buy a satellite – he depicts the symbol of the entanglement between tradition and modernity: cut off from tradition and not reaching modernity. This transaction is repeated later in the purchase of weapons, making this symbol even more vivid. By exchanging radios for satellites, the film wants to narrow the field for tradition and bring people one step closer to modernity: the satellite is the one that brings satellites, and the old people pay for the radios, as if they are bringing modernity and abandoning tradition.

The removal and installation of satellite dishes can also be seen in impressive and beautiful images. When children all together carry the dish on their hands and face the sky, it is reminiscent of images of Western communication advances, where dozens of satellite, telecommunication or astronomical dishes are installed on their bases in a vast plain, but here it is held on children’s hands to show the industrialism of the West and instead of turning us away or staying away from this industry and showing us more attention to human power than to the scientific and mental power of individuals.

The satellite, which with its logic convinces the elders that some channels are forbidden and some are permitted, is a symbol of the leadership of the younger generation. He says that any phenomenon, even the arrival of the Americans, can be positive or negative; what matters is the way it is used. The mosque loudspeakers are used to inform the camp of the news, and Ghobadi proclaims the reconciliation between the mosque and technology. But this modernity is criticized: Satellite seeks social prestige by repeating irrelevant English words (“Hello, hello, master”) and openly says that bread and status lie in this speech. He makes a mistake in translating the news under pressure from the white beards and, with bitter humor, abandons the channel on an Arabic network: “This is the right channel, you know Arabic!” This moment shows the dominance of Arabic culture over the elderly and Western culture over the young, and burns both generations under the domination of foreigners. The absence of Kurdish channels is a criticism of the absence of a Kurdish voice in the global information chain.

Satellite symbolizes the loss of Kurdish identity. With the prestige of a blanket of clothes and a foreign language, he longs for the arrival of Americans. But in the end, with a body wounded by the weapons of the same Westerners, he turns his back on them and limps off the stage, perhaps to regain his lost identity. Ghobadi leaves it up to the audience to decide whether he reaches his goal or not.

The film also criticizes the actions of Western societies: the children who collect mines and take them to the market to sell them criticize the actions of Western societies, as the same ones who today shower us with messages of support, friendship, and brotherhood, once supported Saddam and prepared him with claws and teeth so that the children of this land would be buried by their mines.

The camp, which is divided between Iraq and Turkey, shows the division of Kurdistan in detail. An Iranian man searching for a childhood in Halabja sees the Kurds of Iran as sympathizers, as if he himself were a Qobadi running in search of an uncertain future.

Images of war and destruction abound as symbols in the film:

• Satellite, who sits on the barrel of a tank and commands other children from the side of a personnel carrier, is a symbol of dictatorships that have spoken to the Kurds in the language of cannons and tanks.

• The collection of mines by inexperienced children shows the oppression of the Kurds, who risk their lives for a bite of bread.

• Riga’s loss in the corridors of the Pukeh and the call to her parents reflects our own loss amidst fire, blood, and endless wars.

• The necklace of bullets that Satellite brings to Agrin shows the oppression of Kurdish girls who, in all their tenderness, have to hang lead and fiery bullets around their necks, which are the wounds of these same bullets.

• The barricade next to the school shows the displacement of the Kurds and the parallelism of war and education.

• The wounded Satellite in the personnel carrier, who was left without medicine or a doctor, opens and closes the personnel carrier’s hatch with a pulley and rope to show the creativity of the Kurds in the most impossible conditions, but there is no suitable space.

• The goldfish in nylon that Shirko brings to Satellite from the Americans, turn the water red when they are touched, as if we have been deceived by the enemies again and to show that we have taken pleasure in something that has no foundation.

• The wounded satellite, in the personnel carrier, angrily asks everyone to leave him alone, calms down in his reflection. The guard brings him the severed hand of Saddam’s statue. The hand is a symbol of power (military, etc.), and by doing so, he shows that Saddam has lost his hand and that the same people who once made him a hand. Today, they took it back from him and are giving this lifeless hand to the representative of the Kurds (Satellite) so that he may be pleased with it and gain apparent power and prestige.

The Three Layers of the Film: Society, Body, and Soul

The film can be examined on three intertwined levels: Kurdish society (outer layer), Kak Satellite (middle layer), and Hengaw (inner layer). Hengaw symbolizes the quiet and oppressed soul of Kurdistan. With his silence, he speaks of the Kurds’ deprivation of military and scientific power and is nourished by others. He has lost both hands to say that we Kurds have been deprived of both hands (military power) and (the power of science and writing) and moves forward only with our heads (thoughts), mouths (discourse), and feet (continuation of the path).

The Satellite, however, is the passionate body of Kurdistan, a wandering generation that has lost its identity and seeks social prestige with foreign clothes and speech. His large glasses seem to blind him from seeing the truth and he is at war with Hengaw, his soul. But Hengaw reveals the truth through his prophecies and dreams, because he is free and liberated. The body is seduced and shuns the soul, although Satellite uses it for his own gain, a symbol of exploiters who profit from the suffering of others.

Hengaw’s sister, Agrin, is a bridge between the body and the soul. Satellite tells her at their first meeting: “I have been looking for a girl like you all my life.” This is not a love story, but a search for a lost identity. Satellite sacrifices his bicycle, in fact, his most glamorous material possession, to save Riga, Agrin’s illegitimate child.

Ultimately, it must be said that the only thing that can reconcile the fleeing body with its soul is a common pain and wound that brings them together, removes the veils of neglect from its eyes, opens its eyes, and leads it to its identity. This happens when it dives into the pond early one morning to find goldfish, but finds the drowned body of a child and kneels down beside the pond in tears. The soul arrives and there is a meeting point between the two. At that moment, Agrin disappears at the peak. This common wound brings the body and the soul closer together.

From here on, there is no word about the soul, and in the end, Satellite stands on a road, his back to the Americans, and he walks away with eyes full of questions. Has he found his soul? Or is he still wandering around looking for it? This question is left to the viewer.

Therefore, we can show the three layers of the film in these ways, which express a common theme.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The film suffers from exaggeration or haste on the part of the director in some parts, but these shortcomings are so insignificant that they do not cover the strengths of the work. Turtles Also Fly, with its mythological texture and deep symbols, has a high value in Kurdish and world cinema.

Sources:

1- Eliade, Mircea. Myth, Dream, Mystery. Translated by Roya Monajjem. Tehran: Fekr Rooz Publications, 1995.

2- Hook, Samuel Henry. Mythology of the Middle East. Translated by Ali Asghar Bahrami and Farangis Mazdapour. Tehran: Roshangaran Publications.

3- Henles, John. Understanding Iranian Mythology. Translated by Zhaleh Amouzgar and Ahmad Tafazzoli. Tehran: Cheshme Publications, 1994.

4- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh. Myths of Iran. Translated by Abbas Mokhbar. Tehran: Markaz Publications, 1994.

5- Statements by Professor Mir Jalaloddin Kazazi, University of Kurdistan Publications, about myth.

Note: This note was published in Sirvan Weekly, issue 331, in April 2005, a few weeks after the film was released in Sanandaj, and was republished on the author’s blog, Tolo Dobara, and several other sites, and is now being reprinted and published here after twenty years with a slight rewrite.