Descent into the purgatory of ritual and narrative

An analytical review of the short film “Descent” by Ashkan Saedpanah

The short film “Descent,” made by Ashkan Saedpanah, is a minimalist, turbulent, and moving narrative of man’s moral and spiritual collapse in the face of unintentional sin and its consequences.

According to Artmag.ir, the story takes place in a rural or urban dawn, centered around a poor, religious, and close-knit family who, while searching for a second-hand bed in a junkyard for their sick mother, unintentionally commit the murder of a young girl.

“Descent” is an attempt to portray the conflict between faith and action, and the confrontation of necessity and freedom in difficult circumstances, using appropriate symbols and atmosphere. Focusing on the conflict between religious duties (bathing, funeral prayers) and the concealment of a crime, the film explores the crisis of conscience between father and son, and finally, with a symbolic and shocking ending, places the heavy burden of guilt on the shoulders of the teenage boy. “Descent” is a psychological drama that is powerful in creating atmosphere and presenting the final image, but in the details of the narrative logic, it suffers from breaks that threaten the believability of the story.

I saw the film for the first time at the Sanandaj Film and Photo Week and it touched my heart. I saw it for the second time at the 71st Sahand Regional Young Cinema Festival in Tabriz and tried to analyze it more carefully. As a festival selection, this film went directly to the Tehran Short Film Festival 2025.

The screenplay is a joint work of Ako Zand Karimi and Ashkan Saedpanah. Editing is by Pegah Ahmadi, and cinematography is by Navid Zare.

1. Theme and Worldview: The Thin Line Between Faith and Darkness

“Descent” can be considered an exploration of the concept of sin, remorse, and the inner contradictions of man on the path of faith and morality. The worldview that dominates the film is the profound theme of man’s fall from innocence. From the very first scenes, the film attempts to paint a bright picture of a poor but religious family. The family’s congregational prayers, the recitation of the Quran, and the kind behavior of the parents portray the world of a religious family to the audience. But this apparent aspect gradually becomes fragmented. The death of the daughter and the father and son’s reactions to it present a contradictory picture of religiosity.

This setting is a prelude to an existentialist descent, a descent in which a good motive (making a bed for the sick mother) leads to a disastrous evil (unintentional murder), and from this point on, the film focuses on the conflict between hidden guilt and awakened conscience. If this conflict had been transformed into an internal philosophical intellectual conflict through more passionate dialogues or the father’s more internal doubts, its social critique would have been doubly effective; and the film’s socio-philosophical critique of the contradiction between outward religiosity and practical conscience would have been much deeper.

The beating heart of the film lies in the way these religious men deal with the unintentional murder. In a surprising paradox, the father and son decide to keep it a secret rather than report the incident to the warehouse owner or the police, but at the same time, they are not willing to ignore their religious obligations. The scene of the daughter’s bathing and shrouding, carried out with the father’s insistence that Mustafa “remain pure” and transfer the burden of sin to her, is one of the film’s most thought-provoking scenes. This behavior raises the question of whether their religiosity has been reduced to a mere formalism.

The film’s worldview is based on the idea that even if a person commits a sin by mistake, he cannot escape its consequences. Sin gradually engulfs a person’s existence and distances him from his initial “pure” state. The father, who finds himself at the end of the road, instead of accepting responsibility (both to the law and to the ritual), asks Mustafa to perform a bath so that he himself “does not commit another sin” and places the burden of sin on his young son, justifying that he will have more time to repent. This behavior is a profound criticism of formal religiosity and pragmatic secrecy. But this heavy burden leads the boy to “fall”; a fall that ultimately manifests itself in the graying of his hair as a symbol of spiritual erosion and the loss of youth and innocence.

In fact, “Descent” is as much about the spiritual downfall of a family as it is about the death of a girl. Although the film’s appearance does not deal with mysticism, the concept of the “innocent” washing away sin evokes deeper religious concepts such as sacrifice and purification.

By naming the characters (Muhammad and Mustafa) and referring to prayer and the Quran, the film creates a religious atmosphere and seems to seek to demonstrate the fact that religiosity is not a slogan, but a heavy moral responsibility. The film cleverly draws a clear line between unintentional sin and conscious concealment. This approach may create an image in the audience’s mind of a gray family that takes refuge in religious appearances to escape worldly punishment. But the important question remains: does the film intend to portray the religious as gray and humane, or with a kind of cynicism, to make them appear hypocritical? Are the names Muhammad and Mustafa, which have a heavy religious connotation, merely symbolic signs or do they carry a specific ideological charge at the heart of the narrative? (For example, the name Mustafa means pure and chosen.) The film’s silence about these contradictions, as much as it fills the atmosphere with mystery, may also border on misunderstanding.

Overall, the film manages to present a universal concept (guilt and remorse) in a local context (religious rituals and poverty on the outskirts of the city).

2. Drama: Narrative inadequacies and dramatic vortex with unbelievable gaps

The dramatic structure of “The Fall” is a line with a symbolic twist at the end, based on a sudden turning point: the fall of the throne and the death of the girl. Before this turning point, the film calmly depicts the life of a family, but after that, it gradually enters a psychological and moral drama, but faces serious challenges in the believability of some events, which affects the drama.

The classic three-act structure, family life and morning prayers (act one), the tragedy of the girl’s death in the scrapyard (act two), and the bath and burial in the abandoned bathhouse (act three)—is quickly engaging the audience with a powerful plot twist (the morning call to prayer, the family’s awakening, and the struggle to find a bed for the sick mother).

The inciting incident, the fall of the metal bed and the girl’s death, creates a psychological conflict that forms the heart of the drama. Turning points, such as Mustafa’s decision to return and bury the girl, and the climax, the girl’s bath with her eyes closed—bring the tension to a head. The resolution, with the appearance of the girl’s ghost in Mustafa’s room and her gray hair in the final sequence, is an open and thought-provoking ending that perpetuates the pangs of conscience.

This open ending engages the mind with questions about forgiveness and guilt, but logical gaps wound the narrative. The plausibility of some of the story elements is severely damaged, which prevents the audience from fully accompanying the characters’ inner crisis.

Structural weaknesses: Plot holes:

The presence of the young girl in the scrapyard, in white pants and a clean coat, without any logical justification for her presence and lack of caution, is unrealistic and deals a severe blow to the realism of the film from the very beginning. This space is rarely a place for young girls to travel in this way of dressing, garbage picking is usually accompanied by middle-aged people or dirty clothes and sacks and garbage sorting equipment, and this is the most questionable part of the story and is unbelievable.

If, before the incident, a plausible identity for the girl had been presented (for example, an acquaintance of the warehouse owner who had come there on a personal matter, or a homeless person hidden among the scrap), the viewer would have gone along with the logic of the event. The absence of supervision in the warehouse, despite the presence of the owner, and his ignorance of the girl, distorts the logic. If an incident or a brief conversation between the father and the warehouse owner distracted him from the presence of the girl in his scrap warehouse, this weakness would have been less noticeable. It is not clear that she is a garbage collector, a worker, a buyer, or an acquaintance. She is simply an “accidental victim” who has become a means of advancing the drama rather than serving the story.

Placing a heavy metal bed on the high roof of a junkyard, which is impossible without a crane or lifting equipment, also seems illogical. Why would a heavy metal bed need to be stored in a high place? High places are usually for lighter objects that are easier to move and transport.

Also, throwing a bed off the roof of a garage without looking down, by two adults, is inconsistent with natural human caution and is itself one of the most unbelievable parts of the film. If one of them had looked down and still not seen the girl, the scene would have been more realistic.

Throwing a heavy object like a metal bed from a high height seems unnatural and contrived, not only from a physical point of view (the possibility of breaking or damaging the bed), but also from a psychological and behavioral point of view, without caution and without checking the space below. If the bed was necessary for the sick mother to use, and is going to be used, why is it carelessly thrown down from above? This behavior contradicts the primary motivation of the characters. Usually in such places and for safe transportation, a rope is used to hang heavy objects downward.

The death of the girl due to the abandoned bed hitting her, without any sound, scream, warning, sound of collision, or human reaction, is unnatural, even though the bed was moving loudly and this practically deprives the sequence of a sense of realism. If the sound of the girl’s footsteps or a scream as the bed fell had been included, the believability would have been enhanced. This complete silence, after the bed falls on the girl, is not only far from the cautious nature of humans and that space, but also violates physical and psychological logic. Rather than being the result of human error, this incident seems to have been designed solely to advance the drama by the writer or director.

The girl’s forehead injury, while she was lying in the middle and under the bed netting with the legs away from her head, is not consistent with physical logic. Based on the injury, it would be expected that the bed legs caused the injury, not the middle of the netting. If the wound were attributed to the impact of the bed edge, this inconsistency would be resolved. In a realistic drama, these are more likely to be interpreted as a technical or logical error. This type of inaccuracy in detail can reduce the impact of the scene.

Leaving the scene of the murder without informing the warehouse owner, the father and son quietly returning to the scene of the incident to pick up the body and carry it to the abandoned bathhouse without attracting the attention of the warehouse owner and others, despite his apparent control over the premises, is a chain of inconsistencies, and the transfer of the body without attracting attention is not consistent with the realities of such environments (security cameras, workers, garbage collectors, customers, etc.). The owner of the warehouse, who has already set aside the bed for the father, and the two of them, upon their first arrival, find out about it, should logically also find out about the end of the work from the two of them, but this follow-up is absent. The absence of the bed in the van when the body is transported (and the elimination of this important element throughout the rest of the film), and the lack of any trace of blood in the warehouse or the van, which is unrealistic. If there had been any hint of a clean-up or a secret escape, these gaps would have been filled.

After the bed is thrown away, the drama unfolds as if there is no world outside of the father and son. The absence of any follow-up by the junkyard owner about the bed or the girl’s family about her disappearance leaves the story in an unbelievable void. The girl’s disappearance, the absence of any sign of her family or relatives, her companions and friends, the warehouse owner’s lack of knowledge of the body or the follow-up to the bed case, all empty the film’s fictional world of logic. In the real world, the absence of these elements is a profound void in the narrative and affects the audience; not emotionally, but because of the disconnect with the real world.

For example, if the film had placed the junkyard owner in a position where he was somehow an unwilling accomplice to the cover-up, or if the father and son were forced to professionally clean up the scene in order to show the owner the situation, the plot would have been more solid. Or if the film emphasized external pressures (such as the warehouse owner’s inquiry about the bed, or the girl’s family’s pursuit), the father and son’s secrecy would become a heroic struggle against a system, and the audience would feel real fear and anxiety. These things would distance the film from reality and make it seem like a story made up to present a specific idea, rather than a dramatic narrative.

The unrealistic isolation of some scenes, such as the abandoned bathhouse with no one but the father and son, undermines believability, according to the Journal of Media Psychology, which considers detail to be the key to immersion. If the presence of a guard or other elements had been added to these scenes, the world would have been more coherent and dynamic, and the suspense and tension deeper.

The presence of the old woman in traditional Kurdish dress among the ruins, while the father is digging the grave, has neither a narrative justification nor a symbolic context built for it. If it is an illusion, whose illusion is it? Either it should have been an illusion of the same girl’s presence, like her presence in Mustafa’s room at the end of the film, or there should have been a justification for the old woman’s presence so that the audience would accept it and understand the boundary between illusion and reality. It is as if they are trying to forcefully insert suspense or mystery, but without any return or answer. If it is real, how does her presence help the story move forward? In a world of silence, fragmentation of meaning, and lack of response to action, such moments are more uncinematic than mysterious.

For a deeper study of the topic and importance of believability in film, see Review and analysis of Short Film “SON.”

3. Form, Aesthetics, and Genre: From Realism to Surrealism

“Descent” begins in the genre of moral and psychological drama/social realism. The film tries to engage the audience by creating suspense and a sense of guilt. But it ends up leaning towards heavy symbolism. Events such as the sudden appearance of an old woman or a girl with a bloody head in the room blur the line between reality and illusion for the audience. This technique, if executed carefully, could have added depth to the drama, but here, due to the lack of repetition or further elaboration, it feels like a passing event rather than a structural element. The film’s genre is a combination of moral and psychological drama. For example, in films like Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” the viewer is constantly torn between reality and the main character’s imagination, which adds depth to the story. But in “Descent,” this ambiguity has no effect on the story’s progress.

The editing, with a balanced rhythm between calm and tense scenes, maintains the flow of the story, but the length of some shots reduces the dynamism, and the abrupt cut to the ending creates a sense of rush.

The film’s aesthetics, especially in the use of light (dawn light, darkness and cold lighting of the washroom) and gray colors and space (scrap warehouse, abandoned building), are successful and create a claustrophobic atmosphere that reflects the torment of conscience and conveys the sense of poverty, loneliness and mystery and the weight of sin well. The use of silence during the digging of the grave is one of the director’s strengths, which shows the depth of the crisis in a minimal way.

The scene of the morning call to prayer, with the dim light from the window, enhances the poetry. The set design, with the scrap truck, the metal bed, and the abandoned washroom, increases the visual believability. However, the design of the abandoned scenes is cliché and needed more creativity.

Visual Inconsistencies:

The film’s biggest formal challenge is its visual and stylistic inconsistencies. The modern painting on the wall of a poor, traditional family’s house is a visual anomaly that is far removed from the family’s worldview and an unnecessary blow to realism. This undermines the film’s visual engagement with the audience as much as the girl’s white pants in the junkyard are illogical. This visual incongruity is not consciously perceived as a semantic contradiction, but as a design error. If this painting was meant to symbolize “wandering souls” or “anxiety,” it should have been placed more carefully in the context of the story. If this painting had been replaced with a family photo or a Kurdish symbol, the cultural authenticity would have been strengthened.

Symbolic Ending:

The final sequence, with the iconic image of Mustafa shirtless and with white hair on the balcony railing, is a poetic, symbolic and powerful cinematic moment. This overnight graying of hair is a metaphor and an existentialist allegory of spiritual decline, forced puberty and old age from the torment of conscience and the burden of guilt that it imposes on a teenager. But it is not consistent with the initial realism of the film and approaches the style of surrealism. If this intense symbolic movement had been coordinated with the gentler visual contexts from the beginning of the film with traces of surrealism (such as the father’s eerie vision of the old woman that is not repeated again and the scene of Mustafa meeting the “ghost” of the girl), the tearing of the film’s realistic fabric at the end would have been gentler.

Symbols:

The metal bed, which symbolizes the mother’s hope for peace and recovery, itself becomes an instrument of death. This contrast is clever, but its execution loses its full impact due to narrative weaknesses.

Mustafa’s hair turning white: This symbol of his spiritual decline is strong, but the father’s lack of reaction to this change misses an opportunity to deepen their relationship.

One of the symbols and a platform to strengthen the film is the use of the night/morning timing for the symbolic opposition of darkness and light, although it has gone beyond its symbolic meaning and acts in reverse.

4. Character, performance and acting: A heavy burden on the shoulders of the father and son

The characterization in the film, although minimal, focuses on the duality of the father and son, who are the emotional pillars of the film. The father represents pragmatic morality (preserving one’s own life and family) and Mustafa represents a living conscience. The anxious looks and short and calm dialogues show their mental state well. The actors’ performances are effective in conveying the inner sense of guilt and hidden anxiety, especially the father’s acting. He has been able to show the false peace of a believer involved in secrecy. The son, with his simplicity and innocence at the beginning of the film, also shows the psychological changes caused by the incident well.

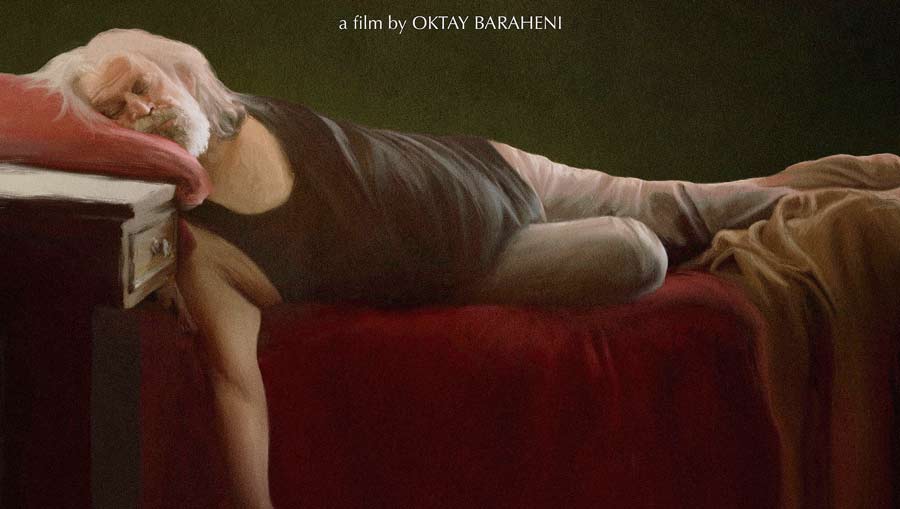

The father, a large man with a white beard and a heart full of love, represents a generation that preaches morality but in moments of crisis, tramples on morality with expediency and fear. Despite his love for his children, the father is more of a symbol of surrender and escape than a leader. He is a combination of faith, fear, and guilt, and shows emotional contradictions at the moment of entrusting the son with the bath.

Mustafa, a 15 year old boy with broken ears from wrestling (a sign of preparation for the national wrestling competition), but despite his mental disability or naivety, somehow represents the film’s innermost moral force. He resists his father’s suggestion, but with his courageous decision to return and bring the body and bathe the daughter and enter the bedroom while seeing the ghost of the murdered girl there, he creates a multi-layered character and accepts the burden of responsibility and even buys the pain of atonement with his heart and soul. The metaphor of her sudden aging at the end of the film emphasizes that true growth and maturity are the product of difficult moral choices.

The girl, who is merely a victim, remains an object, and her appearance with a bloody head in Mustafa’s room, which can be seen as a return to the unburied past, is a symbol of remorse. Here, if the girl’s character had been defined as little more than a symbolic “corpse” and had been introduced to the viewer a little before her death, the dramatic weight of the tragedy would have been intensified.

Muhammad, the younger brother with weak eyes (for whom the mother buys glasses), has a decorative and additional role, and his removal does not change the drama; if Muhammad had also been somehow involved in the internal conflict of the story (for example, as an unwanted witness or an element that makes concealment more difficult), his presence would have given the family a more tangible texture and would have been removed from the status of an additional character. In a film that relies on family relationships and internal actions, each character should have their own role, function, or conflict; the absence of which highlights the weakness in character design.

The mother, with her illness and oxygen tube, is a marginal presence and does not add depth to the story; if she had a greater role in the family’s suffering, the balance of characters would have been better.

The sequence of Mustafa’s blindfolding during the bath, which is an allegory of blinding one’s conscience to commit an inhuman act, represents the peak of the acting and characterization of both characters. At that moment, the father not only hides the daughter’s body from the son, but also protects him from the image of his own sin.

However, some of the initial dialogues and performances, especially in the scene of waking up the children and having breakfast, seem a bit theatrical and artificial, and distance themselves from the natural and believable language of a poor rural or suburban family. If the rhythm and tone of these scenes were a little more natural and less repetitive, the intimacy of the family would have gone beyond a predetermined performance. For example, the father’s requests for Mustafa to take a bath are affectionate but repetitive. The frequent repetition of sentences such as “Mustafa, please do this for me.” In the bath scene and Mustafa’s repeated “I can’t” and the father’s insistence, although indicating the desperation of the father and son, can reduce the dramatic load of the scene and make it artificial and customized, and convey a sense of acting rather than naturalness. If the dialogues were enriched with emotional variety (such as Mustafa’s anger), the believability would have been strengthened.

Character Arc:

Mustafa’s arc, as the “moral hero” of the drama, is successful, transforming from a simple-hearted and innocent boy into a spiritual victim of his father’s tragedy, with the torment of conscience and the moral burden of this act, into a broken person, he is the one who insists on returning and burying him, and he is the one who bears the burden of sin in the end. Especially in the final moment and the boy’s hair turning white, this arc reaches its peak and well shows the destructive effect of sin and the torment of conscience. The father’s arc transforms from a calm and compassionate person to a person who is anxious, helpless and running away from responsibility (although entrusting the son with the bath to avoid further sin is not convincing to the audience).

5. Conclusion and Final Evaluation: Between Poetry and Ambiguity

The title “The Fall”, which alludes to man’s fall from paradise and original sin, poeticizes the theme. “The Fall” is an important and thought-provoking short film, despite its fundamental flaws in narrative logic that weaken a significant part of the film’s dramatic foundations. The film’s strength lies not in its police-crime structure, but in its psychological and allegorical depth. The director’s attempt to address complex concepts such as sin, morality, and conscience in the form of a psychological drama is commendable. The film succeeds in creating atmosphere, using symbols, and showing the impact of sin on the human soul, and its final scene is dramatically impressive.

The scenes of bathing with closed eyes and the final image of Mustafa with white hair are successful moments. The film succeeds in creating a tragic contrast between faith and action and the transmission of sin from one generation to another. However, the film’s main weakness is the lack of coherence and dramatic believability in the basic foundations of the story narrative and some details.

Final Assessment:

“Descent” is among the works that boldly deal with heavy philosophical and moral themes. If the director had spent the energy he spent on creating a symbolic and strong ending, he would have spent it in a balanced way on logically justifying the girl’s presence and eliminating visual contradictions, this work would have stood out not only as a poetic film, but also as a precise and unwavering realist drama. But to achieve perfection in specialized criticism, it should be noted that a work of art, in addition to visual and thematic beauties, needs a solid foundation of narrative logic to become a complete and flawless experience for the audience. This film focuses more on its central idea and neglects to address the infrastructure.

“Descent” is trying to say: even unintentional sin, whether covered up by religious ablution or by concealment, will eventually lead to spiritual downfall (degradation). Among contemporary short films, this work combines courage and depth with visual beauty, but it does not find a perfect balance at the intersection of realism and symbolism.

If the director wanted to draw his work into existentialist metaphors, he would have needed to marginalize the realistic elements from the beginning, and if his goal was to depict the conflict between religiosity and morality, he should have emphasized the storylines of the girl’s character, her family, and the social response to the murder so that the audience does not feel abandoned in a vacuum and without answers.

Ultimately, Descent is a work embroiled in contradictions; both morally and narratively. A film that could have been an influential work in criticizing the religious-social duality, but on the border between realism and formalism and believability, it has sacrificed some of its impact.