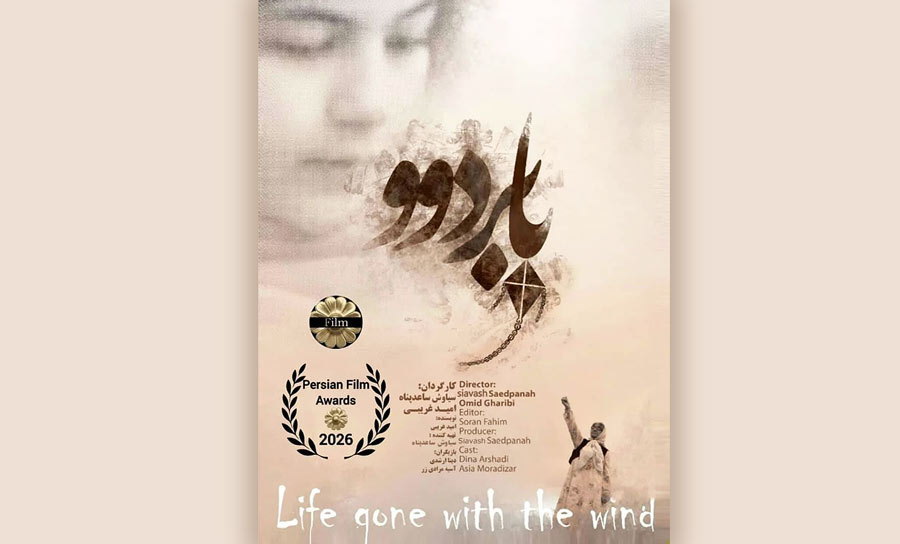

Life Gone With The Wind; An Elegy for Reclaiming a Dream That Was Gone

Criticism and analysis of the short film “Life Gone With The Wind” by Siavash Saedpanah and Omid Gharibi

Short cinema is always an opportunity to condense and depict moments in which “time” does not function linearly, but rather as a knot of longing and desire. The film “Life Gone With The Wind” (in Kurdish, meaning something that the wind carries away, with an allusion to life gone by the wind), made by Siavash Saed Panah and Omid Gharibi, is a tender and bitter tale of childhood nostalgia and the suppression of simple desires in the context of traditional Kurdish society in Iran.

According to Artmag.ir, Life Gone With The Wind is a short film, with little dialogue and relying on images, that, through a narrative that goes back and forth between the present and the past, explores the story of an elderly woman who, as a child, was deprived of one of the simplest and yet most fundamental human pleasures: play and freedom.

The film begins with an old woman encountering a kite stuck in the branches of a hair tree and ends with the kite flying into an autumn sunset; a flight that is more than a physical act, it is a kind of belated realization of the right to life of a lost child.

The screenplay is written by Omid Gharibi, the old woman is played by Asiyeh Moradi Zar, along with Dina Arshadi, Nasrin Mohammadi and other children. The cinematographer is Rahmat Abdiani, the sound engineer is Fardin Molla Salimi, the sound editor is Pejman Raj, and the name of the editor is not seen in the credits.

The film, which had achieved success at the Roshd Festival and dozens of other festivals. I had seen it several times a week at various film and photo festivals, a simple and sincere film, without twists and with appropriate empathy. For the last time, Mr. Saed Panah himself gave me the film file so that I could watch the film again for the final review and evaluation.

1. Theme and Worldview: A Kidnapped Childhood and a Suspended Dream

At the center of Life Gone With The Wind’s worldview is the concept of a “lost child”; a child who has been kidnapped not by death or accident, but by a social and familial decision. Focusing on the phenomenon of child marriage, the film frames it not as a slogan or a direct representation of violence, but rather through the lens of loss, longing, and a mental return to the past.

The old woman in the film carries a repressed memory; a memory that is activated by the sight of a simple kite. This is a smart choice, because in the history of cinematic and literary symbols, kites often represent freedom, play, liberation from gravity, and the possibility of dreaming; from Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner to neorealist films that make simple objects carry a heavy emotional burden. Here, the kite caught in the branches evokes the dreams and aspirations of a child trapped in the tangled grip of traditions and the passage of time; by pulling it out, the old woman seems to be saving a part of her lost existence. By choosing the symbol of the kite as the central element, the director has successfully contrasted the concept of “liberation” with the “bond” (the kite string and the clothesline). However, in expressing this human theme, the film sometimes falls into the trap of visual clichés and prefers to move on the surface of nostalgia rather than deepening the old woman’s suffering.

With the simple but profound act of flying a kite, the old woman not only revives a memory, but also regains a part of her lost identity. This perspective takes the film beyond a mere protest work about “child marriage” and transforms it into a universal portrait of reparation and catharsis. As Paul Ricoeur points out in his theory of narrative memory, the past returns not simply as a mental memory, but in the form of actions, rituals, and bodily habits.

The film’s worldview is one of longing; but a longing that does not end in passivity, but rather, in the last years of life, becomes a small but meaningful action, a hopeful and humane look. Where the personal becomes the bearer of the social without being reduced to a statement, this vision manifests itself not in the form of an explicit social rebellion, but in a personal and internal form: the ability of the individual to reclaim a part of himself, even in the last moments. As Erich Fromm said in The Art of Being, man can search for meaning within himself in the face of external limitations.

The film builds its world on a fundamental contrast: the closed space of the house and the rituals of marriage against the open space of the sky, the wind and the mountains. The house, with its door and threshold and shoes, is the place of destiny; where the girl’s body becomes the property of tradition. In contrast, the kite and the mountains are the promise of liberation, albeit a belated and flesh-eating liberation. The film’s worldview is clearly bitter: the dream may come true, but not at the right time and not with a healthy body.

However, at this same thematic level, the film sometimes hesitates between symbolism and social assertion. The sound of cheers and wedding songs has a revelatory function, but at the same time it carries the risk of reducing complex lived experience to a “warning sign”; as David Bordwell warns about symbolist cinema, when a symbol becomes too transparent, its multilayered power is diminished.

2. Drama and narrative structure; a slow linear narrative with half-hearted suspense

Instead of a classic cause-and-effect progression, Life Gone With The Wind relies on mental associations and sensory cuts; a pattern that is far from Syd Field’s definition of a “three-act linear narrative” and closer to memory-driven cinema. Instead, it uses a cyclical-emotional structure that revolves around an emotional axis: it begins with a sense of curiosity and discovery, moves to longing and remembrance, and finally ends in liberation and pure joy. The climax of the film is not an external conflict, but the moment of the kite flying and the laughter accompanied by the old woman’s cough.

The narrative of Life Gone With The Wind is based on a simple and minimal poetic-narrative structure, with an episodic and flashback-oriented structure: an encounter in the present, the activation of memory, a return to the past, and a return to the present again to fulfill a wish. This structure is, from a dramatic point of view, clear and understandable.

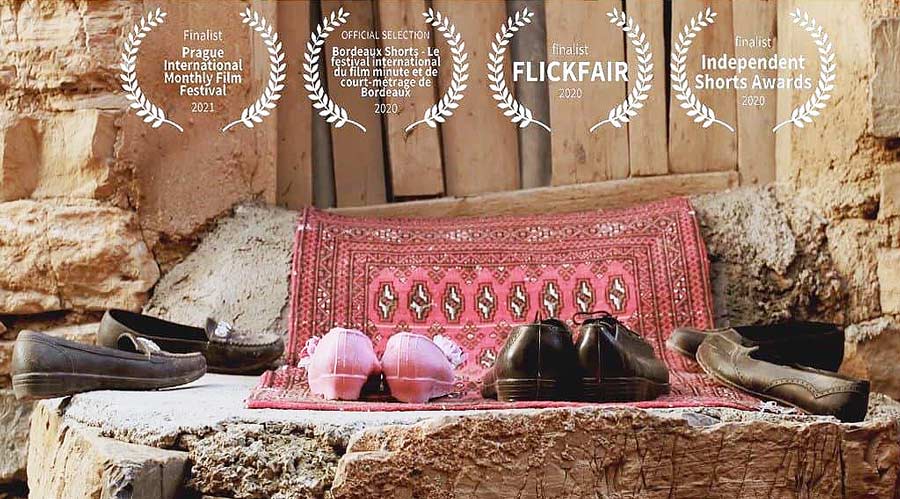

From the perspective of the basics of drama, the film begins with a suitable visual “hook”: the paired shoes of the bride and groom next to a fake red carpet (made from a back) that is part of the film’s middle. This symbolism initially promises a coherent drama. But as the story progresses, the turning points that should strengthen the work’s believability falter.

The hook of the story is the moment when the old woman sees the kite among the branches – a moment that keeps the audience in suspense. The way the kite is discovered is weak. Since the audience sees nothing but foliage in the opening shot, the old woman’s focused gaze lacks a shared “visual reason” with the viewer, although the initial attraction would have been stronger if the camera had shown it earlier. This lack of “shared knowledge” between character and viewer creates a kind of confusion rather than suspense; a suspense that Alfred Hitchcock saw as dependent on knowing more than the character, not less.

The dramatic arc, from the kite repair to the childhood flashbacks, creates a key turning point: the girl’s separation from the game, which is the turning point of the story and introduces the theme of child marriage. This structure is reminiscent of the Aristotelian trilogy in the Poetics, where Aristotle emphasizes unity of action—here, the single action of “recovering the kite” holds the story together. The climax occurs in the old woman’s run under the electricity pylons, where her laughter and coughing mark an emotional landing, symbolizing a bittersweet victory over time.

However, the drama of the film proceeds almost without a hitch in the “present” section. The old woman finds the kite, repairs it, gets in the car, goes into the countryside, and finally flies it. There are no serious obstacles, external conflicts, or dramatic challenges along the way. In contrast, the film’s only real challenge occurs in the past: the girl’s separation from the game, her being dragged home, and her preparations for marriage. This section is the most dramatically effective and tense moment in the film, and it properly serves as the “cause” of all the present action. But the lack of conflict in the present makes the film’s climax seem more like the quiet fulfillment of a wish than the result of a tumultuous journey. If there had been a more serious obstacle or temporary setback in the kite’s flight, the final triumph would have taken on a greater dramatic weight.

One of the obvious dramatic weaknesses lies in the ladder sequence. The director tries to create a kind of “suspension” by making the wooden ladder tremble and unstable under the old woman’s feet; but this suspension does not end in an “event.” Aristotle emphasizes necessity and possibility in dramatic actions in “Poetics,” but here, the trembling of the ladder is only a decorative warning that has no effect on the progress of the story.

Also, the choice of new clothes with the beautiful and bright colors of the girls, especially the color and type of fabric of the bride, and even the red carpet made of a back cover, does not match what happened six or seven decades ago (the old woman’s childhood), and it appears artificial and modern, as if the director has tried to forcefully drag the concept of the red carpet of festivals and the color pink today back seventy years. This temporal inconsistency creates a gap in the film’s realism contract; A gap that André Bazin considered the main danger of realist cinema, because it pulls the audience out of the immersive experience. If the clothes were older or closer to the old color and design, the believability of the time would increase. In contrast, the set and costume design of the present part, especially the house and the old woman’s clothing, is very convincing and rich in detail.

The old woman’s final decision in the resolution section, to get into the car and leave the city and go to the heart of the mountain, to fly a kite, is metaphorically charged from a dramatic point of view, but in terms of behavioral logic, it requires more groundwork. This sudden action, rather than being the result of internal accumulation, resembles a “symbolic solution” and seems a little artificial and made by the director. If the filmmaker had emphasized the subjective aspects more, this action would have been more acceptable. However, the believability of drama, which Robert McKay defines in his book “Story and the Principles of Screenwriting” as the appropriate combination of character traits to pursue desires, falters here.

The believability in this film is based on the emotional axis, not necessarily on accurate behavioral realism. The audience empathizes with the old woman because they understand her fundamental desire to regain some of the lost happiness. However, some details in the transmission of this emotional journey can be challenging and questionable; such as the elderly woman’s attempt to pull out the kite with a very thin stick or branch, which contrasts with the image of an experienced village woman (who knows how to use more appropriate tools and more practical ways). Details that are doubly important in a short film, due to its brevity.

Time, Memory, and Narrative Marking

The movement between the past and the present in Life Gone With The Wind is done in parallel montage and is the film’s greatest narrative challenge. But the film is conservative in marking this temporal transition. Neither color changes, nor changes in image texture, nor clear visual codes such as lens changes or even aspect ratios, clearly indicate that the teenage girls flying kites are the young versions of the same old woman and her past memories, which can confuse the audience at first glance and make them think that while the old woman is repairing the kite, a number of girls and boys are making kites and playing.

However, observing the principle of clarity that David Mamet emphasizes in The Three Uses of a Knife is essential to maintaining a fluid and unobstructed flow of the story. Although this choice can be justified as an invitation to active audience participation and with the intention of blending memory and reality, in practice it creates unwanted ambiguity; An ambiguity that, more than being poetic, weakens the communicative function of the narrative and ends up reducing the impact of the moment of return to the past (such as the scene where the girl separates from the group of children).

In the theories of cinematic narrative, including what David Bordwell proposes about the “signs of narrative comprehension”, it is emphasized that even in minimal cinema the audience needs a minimum of temporal coding. With simpler measures, Babardov could have made the bond between the old woman and the little girl clearer and more effective, without resorting to explanation or visual exaggeration. In the theories of visual narrative, including those of Christian Metz, temporal marking is not an aesthetic requirement, but a condition for a correct reading of the narrative. Here, the film relies too much on the audience’s guesswork.

3. Form, Aesthetics, and Genre; On the Border Between Reality and Memory

“Life Gone With The Wind” falls into the genre of dramatic-social short film with traces of neorealism, with elements of nostalgia and poetic realism, similar to the style of Iranian short cinema that relies on visual details to express themes. A tradition that has continued from Kiarostami and Shahid Thales to contemporary short filmmakers. Closed frames of hands, emphasis on environmental sounds (rustling leaves, breathing, coughing), and the avoidance of dialogue all serve a sensory experience and all help create a sense of lived experience.

The camera attempts to create a sensory space by using close-ups and extreme close-ups of the old woman’s wrinkled hands and the details of the kite being sewn and repaired. The film’s form, with its close-ups and extreme long shots of the mountains, creates an aesthetic that matches the autumn and yellowing of the leaves with the character’s aging – a symbol of the passage of time, which would have been more poignant if it had been more in tune with the early warning music.

The film’s form is entirely at the service of the subject, almost forgoing dialogue and leaving the burden of narrative to the image, sound and music. The cinematography (Rahmat Abdiani) focuses on textures – the wrinkles on the face, the texture of the ladder’s wood, the kite strings, the yellow leaves in the hair – to convey the old woman’s sensory world to the audience. The use of close-ups of the hands, which are both tools of daily work and tools of dream-making, is clever. The camera movement is often slow and contemplative, in keeping with the rhythm of the old woman’s life. The visual aesthetics reinforce the ideological implications through shadows and sunlight through the clouds.

Sound plays a key role in this film. The rustling of leaves, the creaking of the rope, the panting of the old woman as she climbs the mountain, and finally, the combination of her laughter and coughing, create a very vivid soundscape. The low-pitched music, used in key scenes, serves more as an emotional emphasis than a guide to emotion.

In the final sequence, the presence of electricity pylons in the heart of nature creates a double reading: on the one hand, a sign of the modern world that overshadows traditional life, and on the other, a visual element that can reinforce the theme of repression and the transfer of confiscated energy, given its relationship to the old woman’s body.

In terms of genre, the film oscillates between social drama, silent melodrama, and allegory. This fluctuation sometimes leads to semantic richness and sometimes causes the film to be unable to decide to what extent it should be realistic or metaphorical.

4. Character and Performance; Acting as Memory

Asiyeh Moradi Zar’s performance as the old woman is the most important pillar of the film. Her performance is based on the body, gaze, and breathing rhythm, and avoids exaggeration. Her eager eyes and smile while repairing the kite give emotional depth, her trembling hands, short pauses, and hidden fatigue in her movements convey years of suppressed life. Her facial expression when she finds the kite and that trembling smile reveal her inner world more than any dialogue.

The combination of laughter and coughing at the end of the film is one of the most precise moments of performance; where joy and exhaustion, life and decline, are simultaneously present in the character’s body. . The performance, focusing on body movements – such as slowly climbing a mountain – increases believability, the main character of the film, without a name, is more than an individual, a symbol of a generation and a collective destiny. However, Asiyeh Moradi Zar’s performance gives this symbol flesh and blood and life.

Her performance is based on the rhythms of the body: the slow, cautious movement in the house, the trembling hands on the ladder, and then the sudden outburst of a childlike energy in the running and laughing scene on the mountain, which is one of the most precise moments in the film. Her face, especially in the close-up when she sees the kite and then when she repairs it, is a complete dramatic scene in itself.

The minor characters (the children) appear more as dramatic performances than as complete individuals, symbols of lost dreams and freedom. In contrast, the mother character in the flashback, by pulling the daughter out of the game, symbolizes social pressure, which Nasrin Mohammadi’s performance shows with delicacy. She becomes more of a type than an independent individual; a symbol of tradition and compulsion, not a character in conflict. If there had been even a subtle hint of doubt or social pressure on her, the human layer of the narrative would have been richer.

The film is almost dialogue-free and relies more on the body and image than on words. This is a strength for a short film that wants to speak with “image” and relies on facial expressions and deepens the characters. The single sentence “Let me go” from the little girl’s mouth seems practically superfluous; because the physicality of her body and her being pulled by her mother carry the entire load of meaning and if it were removed, not only would it not have taken anything away from the narrative, but it would have strengthened the film’s wordless coherence.

5. Comparative Section; Babardo in Relation to Mohammad Shirvani’s “Circle”

It is impossible to write about “Life Gone With The Wind” and not mention the acclaimed film “Circle” (by Mohammad Shirvani – 1999, winner of the Cannes Film Festival). The thematic similarity of these two works is undeniable; both deal with the repressed “child within” that awakens in old age. But the difference lies in the “performance” and “dramatic geography”. In “Circle”, the old man rolls an iron hoop in the heart of modernity and among apartments; this contrast between the traditional object and the modern space adds a critical layer to the text. But in “Babardo”, the old woman takes refuge in nature. This choice may be due to the “feminine conservatism” in traditional societies, where the old woman prefers to realize her dream away from the eyes of society and in the solitude of the mountains.

In The Circle, the old man faces challenges not only in the past but also in the present: finding a collar, trying to play in the urban space, the gaze of others, and the limitations of the old man’s body. The city acts as a field of friction, and every action is accompanied by an obstacle. This makes the old man’s play full of tension, failure, and retry.

In contrast, Life Gone With The Wind has a seamless and unobstructed narrative in the present. The old woman achieves her goal almost without friction, and the main challenge remains solely in the past, which is the separation of the little girl and her forced marriage. This difference is one of the reasons for the greater dramatic appeal of The Circle. Also, by using a different color scheme for the past, The Circle draws the boundaries of time more clearly and shows the relationship between the old man and the little boy better and more clearly, while Babardo leaves this distinction to the memory and mentality of the audience.

However, Life Gone With The Wind, by choosing a female character and linking child marriage with memory, enters a field that Dere does not address, and from this perspective, it has an independent identity and a specific social concern, even if it has obvious similarities to Shirvani in form and idea.

On the other hand, Life Gone With The Wind is almost without dialogue, and Dere has more dialogue and monologues. Shirvani uses the collar as a symbol of the cycle of time and its circularity, and Saed Panah and Gharibi use the kite as the central symbol of their film, which symbolizes freedom, liberation, and the height in the skies.

Final Conclusion and Evaluation

Life Gone With The Wind is an honest, humane, and influential film that, with its simplicity, creates a depth of nostalgia and social criticism that, relying on images, bodies, and memories, presents a narrative of a kidnapped childhood and a reclaimed dream.

The film succeeds in creating a sense of place, casting, and central idea, but the dramatic delivery, timing, and believability of some of the actions could have been more precise and challenging, and there is room for improvement – if more challenges had been created for the character, its impact would have been more lasting.

The film’s structural and executive weaknesses are mainly summarized in the details of the set and costume design of the flashback section, and the lack of a clear visual separation between the two timelines. Also, the reduction of physical and dramatic challenges on the path to achieving the old woman’s goal makes her journey seem a little smoother and more direct and unobstructed. If this journey, even in nature, had been accompanied by more small and symbolic obstacles, the climax of achieving flight would have been more fruitful. However, “Bobberdo” achieves its ultimate goal as a poetic short film.

“Life Gone With The Wind” shows that although the wind may take away dreams, memory is the thread that still connects us to the sky of childhood. The film shows that some dreams, even if they do take flight one day, carry the weight of lost years. At its best, the film speaks not of liberation but of belated liberation; and that is its most important achievement. Some dreams, however late, can still be delivered to the sky.