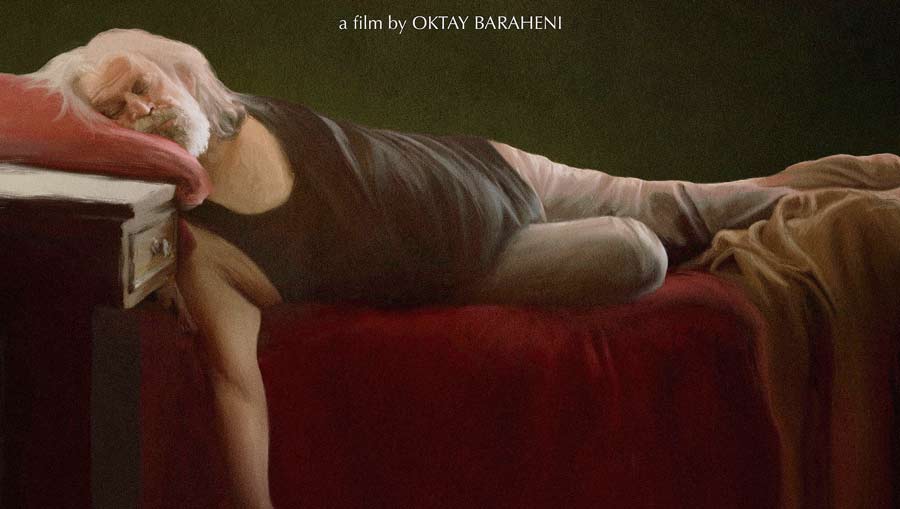

“Cold Dawn”, a narrative of anger on the verge of forgiveness

The short film “Cold Dawn” (2023), directed by Mohammad Hossein Ramezani, presents a realistic and psychological narrative that is outwardly calm but internally full of turbulence and layers of the confrontation between anger and forgiveness in the face of death and justice.

According to Artmag.ir, the story begins in a gray city, where a crowd has gathered in the street around the gallows of a serial killer. This world, with visual details such as the simple clothes of the people, the sound of the death sentence being read, and the lifeless walls of the bathhouse, creates a realistic atmosphere that is tangible to the Iranian audience.

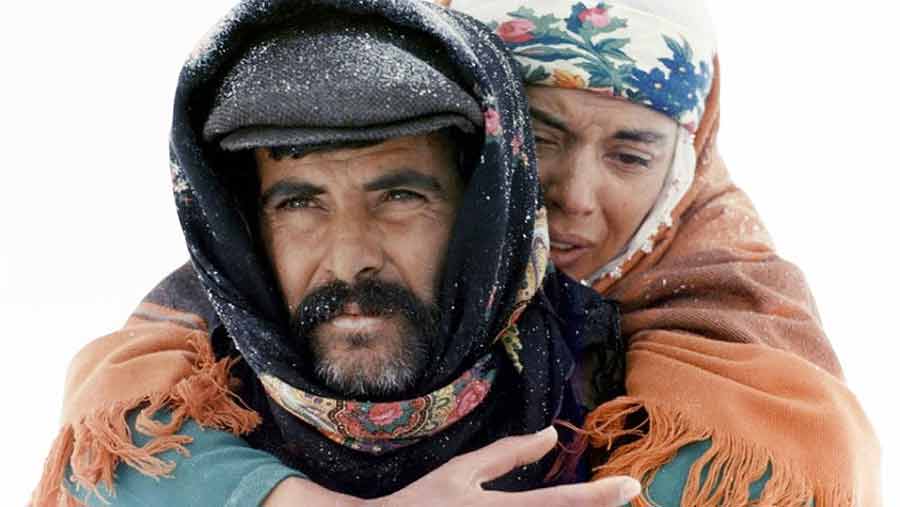

Meanwhile, a middle-aged man (Siavash Cheraghipour), the father of the victims, watches the scene silently and gravely. The main drama, however, takes place in a cold and gloomy bathhouse, where he is forced to bathe the body of the murderer – the man who took his wife and perhaps his daughter from him.

This forced encounter plunges him into a whirlpool of grief, anger and doubt. During the bathing process, the man undergoing the bath experiences a severe conflict with the onslaught of past memories, and finally, when the murderer, at an unexpected moment, shows signs of life, the man is faced with a huge question: Can you forgive the murderer of your loved ones? That is when he must choose between personal revenge and a human decision…

The film “Cold Dawn” attempts to go beyond the level of the incident (murder and execution) and delve into the depths of an individual’s emotions and moral choices.

This film, which has participated in festivals such as the 41st Tehran Short Film Festival, the 20th Nahal Festival, the 11th Milazzo Festival (March 6-9, 2025), the Rasht Festival 1404, and …, despite its strengths, suffers from logical gaps that weaken its credibility.

In this analysis, relying on the theories of narratology and psychological cinema, the thematic layers, form, and ideological implications of the film are examined in order to reveal the world that Ramezani has created to readers.

I saw this film at the Third National Rasht Film Festival. Its drama attracted me and its believability repelled me. Now, this analysis, inspired by Robert McKay’s concept of believability in fiction, which he considers to be the coherence of the internal logic of the story world, and referring to David Bordwell in Narrative in Fiction Film, which emphasizes the importance of narrative structure, examines the film along four main axes, and all the strengths, weaknesses, and thematic and ideological implications are included in this analysis to illuminate the hidden layers of this work.

What follows is a narrative of denial, anger, and the possibility of rebellion in the face of immense suffering, which, with minimal visual language and narrative, forces the audience to reflect on the meaning of forgiveness and justice.

1- World and Theme: A Gray City with Invisible Wounds

The worldview of “Cold Dawn” is rooted in a human and moral critique of the concept of justice and revenge. The film depicts a cold and isolated world in which individual suffering remains silent under the shadow of social rituals – such as public executions.

The psychological drama genre with social veins creates an isolated and thought-provoking world that serves the film’s central theme – the confrontation between anger and forgiveness – which is deeply human and universal, but this confrontation goes beyond Ghassal’s personal story to a critique of the concept of justice. The execution, which is supposed to achieve justice, is questioned in Ghassal’s psychological background: will the murderer’s death heal his suffering? This theme is reinforced in scenes such as Ghassal’s fists on the corpse or his hesitation in the face of the resurrected murderer.

These questions, rooted in moral philosophy, make the film more than a simple drama. As Aristotle says in the Boethius, drama should arouse the audience’s emotions and create catharsis; “Cold Dawn” achieves this goal at times, but neither perfectly nor flawlessly.

However, the lack of deep exploration of the killer’s motives and the whys and hows of the murder, or the social subtexts, such as the impact of public executions on the psyche of a society, have deep critical potential, but the film is conservative in its development, limiting the opportunity for more multilayered criticism.

The film’s title – “Cold Dawn” – is itself a double-edged metaphor. “Dawn” promises beginnings and hope, but “cold” renders it devoid of warmth and life. It is as if the film’s world is on the verge of passing through night, but unable to warm up. This dichotomy beautifully reflects the contrast between mercy (the bath) and violence (the execution). The film’s worldview, which praises forgiveness over revenge, appeals to a global audience.

2- Narrative and Conflict: A Turbulent Arc in the Shadow of Logical Gaps

The film’s narrative begins by choosing a linear narrative style; the execution scene, the transfer of the body, and then the main character’s entry into the washroom. This classic beginning quickly introduces the viewer to the situation. The use of flashbacks as a tool to show the character’s past and his conflict with the memories of his wife and daughter also adds to the dramatization of the present moments. The film’s rhythm is appropriate and proportionate, allowing the main character’s inner tensions to be felt well.

“Cold Dawn” uses a classic three-act structure, which, according to McKay, is a solid foundation for character-driven dramas.

The first act begins with a public execution, which is the inciting event of the film and introduces the gray world of Ghassal.

The second act places the court official, Wali Dam (the washroom man), in charge of washing the murderer’s body. This assignment of duty creates a deep inner conflict in the main character and places him in an unimaginable situation.

So the first turning point, assigning the task of bathing to Walid, creates a psychological conflict that drives the story forward. This moment is the “trigger of the dramatic transformation” that leads Ghassal towards a deeper conflict.

Ghassal’s entry into the bathhouse and encountering the murderer’s body is a key moment. Upon seeing the body, he has flashbacks to his memories of himself, his wife, and his daughter, deepening Ghassal’s feelings of sadness and anger.

The dramatic turning point of this act is when Ghassal punches and slaps the corpse, unleashing his pent-up anger. This moment is the peak of his emotional outburst, followed by his kneeling and crying beside the corpse, indicating his inability to overcome his suffering.

The third act reaches the emotional climax of the drama as the killer comes to life and Ghassal tries to strangle him, and this scene elevates Ghassal’s internal conflict (revenge or forgiveness) to a physical level. With the same anger and recollection of memories, he squeezes the killer’s throat to strangle him. (This scene, while dramatic and shocking, is the film’s biggest Achilles’ heel in terms of believability.)

The resolution, with Ghassal’s exit and the hint that the killer is alive, creates an open and thought-provoking ending. This approach, rooted in the tradition of Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema, allows the audience to participate, but here, without a solid logical foundation, it remains more of a suspense than a thought-provoking one.

The film’s point of view is largely subjective and internal. We identify with Ghassal and enter his mental world and suffering through flashbacks and his reactions.

Believability and Dramatic Story

According to Bordwell, believability depends on creating a coherent world. “Cold Dawn” succeeds in creating a realistic atmosphere. But in a world that is designed with precision and detail, logical gaps distort the coherence and believability of the narrative.

First, (the assignment of the duty of washing the body to the deceased’s guardian by a law enforcement officer without any logical justification, after the guardian’s refusal to forgive and the execution of the murderer, is very unlikely and unrealistic in terms of story logic). First, is this possible by ordering and assigning a simple law enforcement officer, without the presence of himself or one of the officers?

Such an incident in the story was the simplest and easiest choice and decision of the screenwriters, who have simplified the task greatly. Second, in Iran, ghosl is not a specialized matter that only one person in a city or a large region can do, or they cannot wait for another opportunity and another person, and entrusting it to a person with such a conflict is not consistent with judicial and customary logic, and that too without any supervisor, assistant, or replacement, even from among the murderer’s family. While this decision carries a heavy dramatic load, it breaks the boundary between narrative and exaggeration without any introduction or logical justification.

This choice of script is more like a dramatic advantage than logical reality, and is designed solely to create a conflicted situation for the main character. It seems that the filmmaker has sacrificed narrative logic in order to reach a dramatic climax.

Second, (The police officer’s failure to hear the sounds of Ghassal’s punching, crying, and screaming in the washroom and his lack of reaction to it is illogical, given the small space and lack of soundproofing, and the ordinary doors and windows that do not have much fastening). This is especially true when the police officer is sitting alone, leaning against the wall of the washroom outside, and there are no disturbing sounds such as the sound of the wind or the washroom motor or the sounds of workers and machinery nearby. This greatly reduces the believability of the scene.

Third, and most importantly, (It is almost impossible for the murderer to come back to life after being executed by Ghassal’s punches, from a medical and logical perspective). According to official execution protocols, the executed person remains on the gallows for several minutes, the executioner confirms death, and then the body is transferred to the morgue and the forensic doctor, and finally to the washroom, and is prepared for a bath, shroud, and burial. The probability of coming back to life after this process is close to zero and unbelievable. (This scene, which seems designed for dramatic shock, instead of enhancing the drama, pulls the audience out of the world of the film.)

This is the film’s biggest and most inexcusable weakness. This incident is completely out of context. In a film with a social and dramatic genre that seeks realism, such an element is extremely implausible and undermines all the filmmaker’s efforts to create real drama and conflict. (If the film were to move towards fantasy or magical realism, such an incident could be justified, but in the current context, it is a major flaw in the script.) As Northrop Frye says in his book “Anatomy of Criticism”, realistic drama requires compliance with the laws of causality and possibility in the world of the work. The resurrection of an executed person violates these rules and resembles more a psychological fantasy than reality.

If this scene were clearly presented as an illusion or a psychological reflection of Ghassal, it would be in line with the film’s internal logic. In its absence, the audience is faced with a narrative break: a moment that shakes belief.

3- Character and Performance: A Cry in Silence

Ghassal, played by Siavash Cheraghichur, is the emotional pillar of the film. With minimal dialogue and maximum emotion, he conveys deep suffering, suppressed anger, and doubt. With fierce looks, silent cries, and delicate movements, he creates a complex and multifaceted character: a victim who is both judge, executioner, and savior.

Believable acting evokes the audience’s emotions, yet the film could have had more opportunities to deepen Ghassal’s character.

If his relationship with his family, or his past with the killer, had been narrated in more precise detail, the audience would have been better able to judge between his forgiveness or revenge (we still don’t know if it was just his wife who was the victim, or his daughter, or both? When, where, and how the murder took place?). Now, with limited information, Ghassal’s final choice seems more like a symbolic gesture than a well-founded decision. (His act of strangling the resurrected murderer is too sudden, without psychological context, such as signs of a nervous breakdown.)

His character embodies what Carl Gustav Jung called “the shadow”: a dark, repressed part of us that sometimes overwhelms us.

The strength of the narrative, however, lies in Ghassal’s psychological arc, as a man who goes from being a bath attendant to an activist in a moral struggle. Flashbacks bring his past to life, but not enough to fully flesh out the motivations and depth of the character. Some of these flashbacks are repetitive, and more like reminders of tragedy than emotional connections. Especially since the attentive audience is waiting for signs of deep attachment, a moment of loss, or psychological fragility in Ghassal, which rarely happens.

Ghassal’s transformation from anger to doubt seems rushed due to the lack of sufficient grounding. According to Syd Field, the transformation should arise from gradual choices. If the film had shown Ghassal’s moments of doubt or inner collapse, his transformation would have seemed more natural.

The character of the murderer, who is present only in the form of a corpse, is effectively absent and remains an object, a mere stimulus to the drama, not an independent actor. (His resurrection, although a key moment, has the opposite effect because it is unreal.) If the murderer’s presence – even in a brief flashback – had taken on a more human tone, perhaps the film’s moral conflict would have been more pronounced: the forgiveness of a human being, not a corpse.

Other supporting characters, such as the police officer, have typical, functional roles and do not add depth to the story or have a chance to shine, and only act as plot drivers or background to deepen the main character.

4. Form and Aesthetics: Poetry in the Shadow of Monotony

The form of “Cold Dawn” is like a sad poem: simple, yet powerful. The cold lighting of the washroom and the gray colors of the streets create a claustrophobic atmosphere that reflects Ghassal’s inner suffocation and evokes a sense of sadness, coldness, and death. The flashbacks, with their warmer colors (the park and sunlight), create a poetic contrast to the coldness of the washroom, which shows the contrast between life and death. This contrast is reminiscent of Anthony Giddens’ approach to the role of symbols in social identification: Ghassal, from within a symbolic system (death, purification, law), must make a decision that redefines his human identity.

The lack of more creative visual elements—such as symbolic shading or camera movements—leads the form from uniformity to stillness.

Direction and Editing

Ramezani’s direction, with its attention to details like the washroom stone and meaningful silences, creates a tangible world and a minimalist signature.

Editing by Komail Arjomandi, with smooth cuts and a balanced rhythm, maintains the story’s rhythm, but (the monotony of the washroom shots and the repetition of flashbacks reduces the dynamism.)

The set design, with the washroom stone and the cloth on the corpse, enhances visual believability. The sound design and composition, the muffled moans and screams of the washroom and the sound of the fists on the corpse, especially the sound of the murderer’s heavy, muffled breathing, make the moment of coming to life poignant. Majid Aghaei’s minimal music deepens the mood.

Symbols and Metaphors

The washroom: The ritual of washing the body in this film is not only a preparation for burial, but symbolically can mean a rite of passage from hatred, a spiritual purification, and even a kind of rebirth for Ghassal. If Ghassal can ghosl his family’s murderer, he has been able to escape the clutches of anger. This ritual, usually associated with ablution and cleanliness, here creates a dramatic contrast to the filthiness of the murderer’s actions and Ghassal’s grudge.

Washroom location: This place is the boundary between life and death, and a place for the final “cleansing.” Ghassal’s placement in such a space emphasizes his loneliness in this inner confrontation and the importance of cleansing the soul of grudges.

Washroom stone: Cold, lifeless, and merciless, this stone could be a metaphor for Ghassal’s wounded heart. The placement of the murderer’s body on this stone is reminiscent of the heavy burden of anger and resentment on the shoulders of the murderer.

Water: As an element of purification, it is contrasted with this coldness.

5- Final Evaluation: A moving drama with the Achilles heel of believability

“Cold Dawn” is a bold and respectable work that promises Ramezani’s talent, which tells an impressive story with psychological storytelling, brilliant acting by Siavash Cheraghipour, minimal aesthetics, and subtle symbolism.

Its strengths are in execution, atmosphere, and deep theme, and powerful internal conflict, which make it a remarkable work in Iranian short cinema. However, the logical gaps, which were mentioned in the believability section, keep the film from being a lasting work.

These weaknesses prevent the audience from fully engaging with the film, and instead of focusing on the drama and message of the film, it directs its mind towards logical questions and the reasons for the events, and the film remains without brilliance in the shadow of cold and unanswered logical questions.

Ghassal’s hesitation at the end, although it may not be conclusive, is itself the “stopping” that is the important possibility that vengeful narratives try to suppress. “Cold Dawn” is more than a film about execution, it is a work about possibilities; the possibility of living in suspense, between anger and mercy, death and life.

But a few ways out to shine

If Ghassal’s resurrection had been presented as an illusion, a nightmare, or a psychological experience, it could have symbolized the inner rift in Ghassal’s mind, and the film could have combined its poetics with believability and become a more complete work of art.

As Arsène Kotsou says in his book “Film and Realism,” every realistic work of art requires internal and external coherence, in which imaginary elements should not harm reality. In that case, instead of dramatic shocks, the film would focus on internal conflicts (such as Ghassal’s mental dialogue) or deeper symbolism, and would become a multilayered work.

Another way out would be a suitable escape to the genre of magical realism, which, with the specific context of this genre, could make the murderer’s resurrection believable and direct the story in a different direction.

But if the writer and script consultant had tried harder, they could have narrated the story in a different way with appropriate and appropriate changes in the current style and genre, strengthened the believability of the film, and ended the film with the same content and mood, but with logical foundations and with universal brilliance.