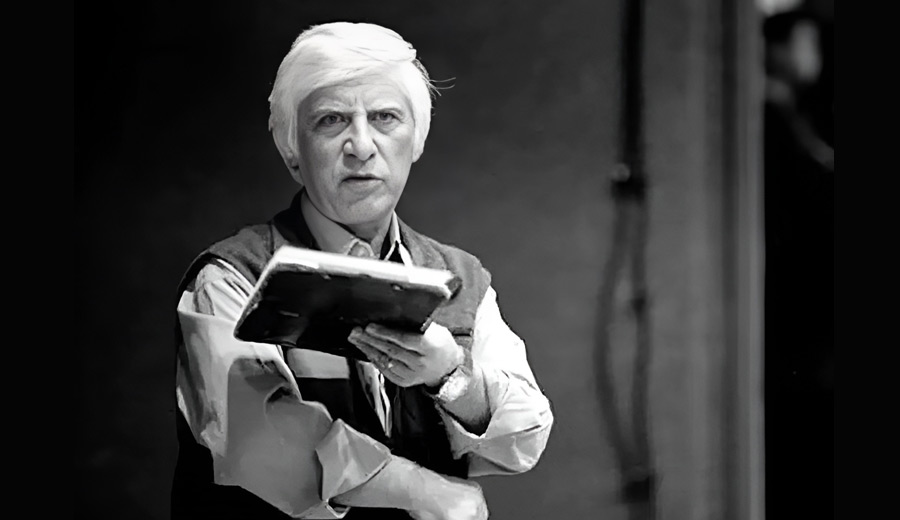

Interview with Albert Koochooei

Albert Koochooei, 82, is only three years younger than Radio; he came to ISNA at Radio’s 85th birthday celebration to represent the people of Radio, expressing his love and passion for the medium that was once his and his generation’s dream.

According to Artmag.ir, citing ISNA, Koochooei says: “Radio was the first medium that entered my father’s house after the newspaper. We were only allowed to listen to the programs for a few hours, and all I longed for was to enter this glorious and dreamy medium.”

Albert Koochooei, born on June 30, 1943 in Hamedan, is an Iranian writer, translator, and radio host.

He moved to Abadan with his family at the age of seven and lived in Abadan until he received his high school diploma.

He was only a teenager who worked with the press and at the National Oil Radio. After that, he worked at Radio Rezaieh as a producer, writer, and Persian announcer and the head of the Assyrian Radio. He went to Tehran to continue his university studies and studied at the language faculties of the Pars High School and the High School of Translation until he received a master’s degree in news.

In Tehran, he worked as a writer, producer, and announcer at the National Radio and Television of Iran and the national press. His social activities in the Assyrian community include three terms as the president of the Parents and Teachers Association of the Hazrat Maryam Educational Complex, and two terms as the president of the Tehran Assyrian Association.

Thanks to his unique voice, he had the chance to realize his dream as a teenager and was only 14 years old when he became the owner of an independent program on the radio!

Albert Koochooei came to the Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA) on the occasion of the 85th anniversary of radio to review his more than half a century of activities in the world of sound. According to his fans, he always has a special peace in his voice. At the beginning of his speech, he talks about his love for radio, saying that radio was a dream for him and his contemporaries, and even television, with its charms, could not cover the grandeur and glory of radio for them.

The name Albert Koochooei is familiar to many people in culture, art, and media. He describes himself as follows: I am Albert Koochooei; born in Hamedan and of course raised in Abadan. I started my professional career in Urmia and then continued in Tehran. I was mostly present on radio; I was the artistic editor of the radio and for five years I had a television program reviewing the press. I pursued my university education in Tehran and my primary and secondary education in Hamedan and Abadan.

Radio still retains its originality, but the form of presentation has changed

This veteran of sound says whether radio has changed in light of the challenges that new media has presented to it? He says: Basically, radio was a medium for my generation. Born in 1943 and raised in the 1940s and 1960s; the most important medium at that time was radio, and even the appeal of television could not cover the awe and splendor of radio.

Although I also had some experiences in Abadan Television during my high school years. Radio has always changed with time. After the emergence of the press and new media, radio acquired a different identity. It needed to act quickly, and it is natural that in the following periods, that is, in the following decades, radio changed its identity. That is, its form of presentation changed until today.

Today, we witness hundreds and thousands of radios in cyberspace

Albert Koochooei believes that radio has changed from the past to the present: Indeed, we are witnessing hundreds and thousands of radios in cyberspace. Radio has still retained its originality and roots, but its presentation has changed. Now, a user in cyberspace can own a radio, a television, or a newspaper. This is both desirable, noteworthy, tempting, and risky; because in an official media outlet like radio, there is always the presence of an editor, producer, and manager, who protects the different tendencies of a writer and speaker, but in unofficial media, an individual does all these things himself.

Radio also had a close presence during the Holy Defense

Koochooei recalls the influence of radio during the imposed war: During the war, radio had a close presence. In the eight years of the Holy Defense, we see that radio becomes very prominent and has a close presence, and even today, despite hundreds and thousands of radios, official radios are still the source, purpose, and target of an audience that seeks accuracy, clarity, and precision.

I was never enamored with fame

Koochooei speaks of his love for radio and narrates how he entered the field of sound as follows: Radio was the dream of my peers. Radio was the first medium that entered my father’s house after newspapers and the press. We were allowed to listen to the radio for hours, and all I wished for was to enter this glorious and dreamy medium.

By chance, I participated in a competition, and in that competition, the person who ranked first was usually asked to perform any art; sing, play an instrument, or other than these, which I said I would recite. I remember reading a poem by Parvin Etesami, which was: “If her black soil is her bed/The star is the wheel of Parvin’s manners,” and I read the poem to the end. Through the glass in the control room, I saw a man constantly walking back and forth with a smile on his face. When the program was over, when I entered the control room, I saw the then director of the radio, Mr. Fatorechi, whom I never saw again after working in Abadan, saying that your voice is a distinctive voice. I was 13 or 14 years old at the time and a high school student. He said, “We want you to participate in radio drama programs.” I said, “If my father allows it, then definitely.” And they invited my father. My father said that he would not mind as long as his studies were not harmed, but as soon as I saw that his studies were being harmed, I would prevent him from attending. Fortunately, such an incident, which my father sometimes saw as a black eye, did not happen.

After a week or two, at the age of 14, I had my own independent program and became a celebrity, as they say today. On Radio Abadan and wherever I went, they would point fingers at me; perhaps this was the greatest blessing that came my way.

I experienced fame in my teenage years and saw what qualities a famous person should have, what pleasures they had, and what dangers lay in their path. This is why after a year or two at Radio Naft Abadan, I never became enamored with fame, that is, I never boasted.

Sometimes when they saw me on the streets and I was already a well-known face at that time, especially in the 40s, and they would compliment me, my late wife would say to me, “Why are you thanking me so coldly?” And I replied, “I know these are fleeting and forgettable words that really gave me the opportunity to never be enamored, infatuated, and humiliated by fame.”

This veteran announcer says about the secret to his longevity on the radio: “I am truly enamored with radio. Radio is a convenient medium. At one point, I was a sound engineer, producer, and broadcast operator at Urmia Radio; of course, my own work was also writing, presenting, and producing; that’s because I knew all the methods of this medium, and then of course I was attracted to television. But I was always enamored with radio.

I thought that millions of people were now listening to me, and my behavior, my interactions, and my presence in society, especially after being behind the camera and behind the microphone, were my thoughts; that’s why I was always enamored.”

Albert Koochooei’s voice inspires the composer

There are several lasting definitions for Albert Koochooei and his voice; for example, a musician has said in describing his voice that he feels the exact oscillation of the note and a special music in Albert Koochooei’s voice and lives with it, and many of the works he creates are inspired by the melody of Albert Koochooei’s voice. Mohammad Saleh Ala also says that when Albert Koochooei speaks, the birds fall silent.

Regarding this description, Mohammad Saleh Ala says: I thank him; we are also very old friends and colleagues and we had a long working life together.

A Different Alley by Fereydoun Moshiri

When we ask Koochooei to read us a few minutes of his favorite poems, he accepts sincerely and reminds us: My radio life really began with poetry, and to this day, poetry fills a large part of my reading hours.

In the 1960s, with other radio friends and colleagues such as Farhang Joulaei and Amir Nouri, we published a collection in which we also read Fereydoun Moshiri’s Alley poetry, which was released in the form of cassettes and tapes that became popular. We performed it together with the female announcer, Fakhri Nikzad.

Of course, I read the Alley poetry with a different rhythm than the late Fereydoun Moshiri himself, and I owe this to Morteza Okhovat; an announcer who was my editor in the 1940s and 1950s. The meter and an innovative rhythm that I remember were the main factor in it, Nader Naderpour, and they introduced this innovation, and I imitated it.

Like the verses “Without you, moonlight, I passed through that alley again one night/ I became all eyes, I searched for you/ The desire to meet you overflowed, I became the cup of my being/ I became the crazy lover I was”; in fact, the beat is completely different, and during the recording, I remember arguing a lot with the female narrator about keeping this rhythm, but naturally, she had followed a different method.

Reviewing the poems of “M. Azad” in solitude

He continues: But I am more fascinated by the poems of Mahmoud Mosharraf-Azad Tehrani than “Kocheh”. He was my literature secretary in the 1940s and 1960s in Abadan and introduced me to the world of literature and poetry, and in his memory I always whisper this poem. I am reviewing a poem by Mahmoud Mosharraf-Azad Tehrani (M. Azad). “Without you, I am alone in the plain/ Without you, my cold love of the evening/ Without you, I am nameless and lifeless/ Without you, my friend” The whispers of my lonely hours are this poem and I follow it.

The Secret of Koochooei’s Peace

In another part of this interview, Koochooei says about his reliance on words and his expressive habits on the radio and in performances; “I always try to be innovative in both writing and speaking. Like a journalist who always thinks and thinks new things, and if one day he doesn’t think and act new things, he is truly dead. This is because I always perform with a different language, and my language is not a repetitive language. My prose and language are always new, and I try to be different every time. Every time it has an appeal for the audience.

He describes the secret of his calmness in performance as follows: This is perhaps one of the blessings that I have been blessed with. If there is any turmoil or confusion inside me, it will never be shown in my voice or on my face. There is always a calmness in my voice and face, which is like the description of one of the composers who said that there is a rhythm and beat in your voice that gives peace to the audience and sometimes at night we fall asleep with your programs and I said with a laugh that it is unfortunate that I put you to sleep! I do not approve of expressing any emotion that is inside me and I am looking for the same peace.

Koochooei talks about the world of press and journalism many years ago, when he was four years old and stated: I started both media (press and radio) together; I started my press work thanks to M. Azad, our literature secretary, who led me to classical literature, and this was a great blessing. Apart from the fact that I was raised in a cultural family where my father was a teacher, my mother was a teacher, my older brother was a teacher, and I started reading at the age of four or five in English, Italian, and Latin, I owe my inclination towards classical literature to M. Azad, who I know led and guided me towards classical literature. I started working in the press with the enthusiasm and insistence of the deceased, and at the same time, I almost started working in the radio, and to this day, after about 60 years, radio is still new to me. Writing is still new to me. When I want to write, I still think, ponder, and review. When I want to speak, when I enter the radio studio, it is as if I am entering a sacred place and entering with prayer.

Radio is my home, but I don’t own my house

This radio veteran responded to the question of when he knows the end of his career and what would be his reaction if they said they no longer want to work with you on the radio? He stated: Many of my programs were abruptly closed by the managers at their own discretion and choice and said that this program would no longer be broadcast from the following week, and I accepted it very easily. In any case, radio is my home, but I don’t own my house.

Whatever the managers, editors, and producers want, I have to obey them and I accept it very easily; just as I accepted it very easily, I had dozens of programs, hundreds of radio programs over the years that have been canceled and I regretted it, I cried inside, but I accepted it and didn’t take it out on myself.

I would like to be on the radio as long as I can write, speak, and be able to speak

In response to whether he has ever thought about the end of his career in radio, he says with a laugh: It has been many years since my career ended, but I still go to the radio. The fact is that I would like to be on the radio as long as I can write, speak, and be able to speak. Of course, I am more fascinated by the younger generation now and I believe that the younger generation should fill the radio and the media. Fortunately, the younger generation that I witnessed during the last decades, the 60s, 70s, and 80s, was a generation that was truly passionate, in love, and obsessed with radio. I saw many young people who were very mature, literate, and passionate about their work; this is why I would rather be a colleague and companion alongside the younger generation than to write or speak.

In his advice to the younger generation, he notes: I have been speaking to audiences for 60 years, but the advice I have for those who are truly passionate about media work, especially radio, television, and broadcasting, is that they should be in love, they should be passionate about their work. As Mahmoud Azad said, they should be in love and go.

If you are not passionate, passionate, and in love with the media, you will lose very quickly. This is because you must go through hardships, bitterness, and hardships and know that there is no support and backing for the media except God and love for it.

85th Anniversary of Radio and an Excuse for Congratulations

85th Anniversary of Radio and an Excuse for Congratulations

Albert Koochooei, while congratulating the 85th anniversary of Radio, said: On Radio Day, I was actually addressed by ISNA.

Many of my colleagues and companions were more worthy than me and more experienced than me, including Amir Nouri, to be present at ISNA. In any case, by bowing down to the generation of radio announcers and colleagues, news agencies and newspapers, I congratulate the precious anniversary of Radio and sincerely wish the stability and longevity of the beloved radio enthusiasts.