Analysis of the short film “Farewell Day”: Drama or tragic memory?

The short film “Farewell Day,” directed by Farzad Ranjbar Nazari, was screened at the 41st Tehran International Short Film Festival (October 2024). I saw it for the first time on the sidelines of this festival in Sanandaj and for the second time at the third Rasht National Film Festival.

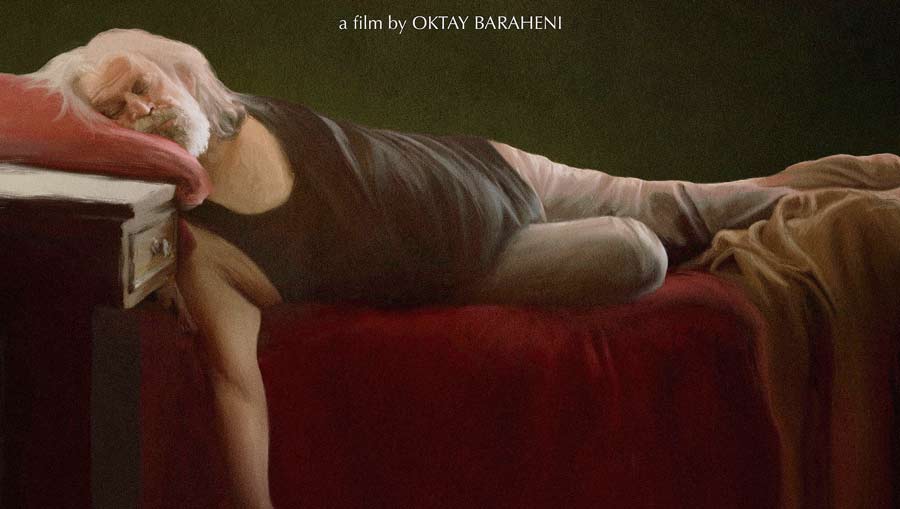

According to Artmag.ir, the work produced by Soureh and Royad Film Club is the story of the last days of Reza, a father suffering from advanced cancer, in a simple house in the city of Sari. Focusing on Reza’s interactions with his wife, young son, and young daughter, the film invites the audience on an emotional journey in the face of death. But does this short work succeed in creating a lasting cinematic experience, or does it simply degenerate into an emotional memory?

“Farewell Day” begins with a moving image: Reza, a thin, ailing father, cries out in pain from cancer and demands morphine. His bony body and bleeding arm wound, which takes place before the eyes of his young daughter, establish the tragic burden of the film from the very beginning.

The story progresses linearly, following the daily life of the family: a wife under the pressure of caregiving and family tensions, a young son on the verge of taking entrance exams who reacts with anger and sadness, and a little girl who speaks with childlike hopes of a family trip.

The narrative progresses with emotional moments such as the delivery of a new car, Reza teaching his son to drive, eating at a pizza place with his two children, and children playing on the beach. These moments culminate in the film’s implied climax: Reza gives his wife a gift in the car and, looking at the children playing, as if the moment of final farewell has arrived, resorting to emotional cliché. This fluid structure, lacking clear turning points or complex twists, brings the film closer to a minimal drama that conveys the feeling of a painful memory.

1. Genre and Story World: A Tangible Drama in the Shadow of Stereotypes

“Farewell Day” is rooted in the genre of family drama and builds a plausible world (Story World Plausibility) by relying on (emotional relationships, death, and farewell). Tangible details such as morning tea, Reza’s cigarette, or the boy’s anxiety about the entrance exam create a familiar atmosphere for the Iranian audience, and these details strengthen the sense of everyday life of a middle-class family and emotional authenticity. However, the lack of cultural complexities (such as Mazandaran rituals, local symbols, or richer spaces) limits this world and does not fully immerse the audience. This work could have taken place anywhere else in Iran because it does not carry any signs of the color, clothing, language, or dialect of the Sari region.

“Farewell Day” can also be classified as a minimal psychological drama or existential drama; A genre that focuses on human experiences, complex emotions, and everyday life, sometimes departing from the classic structures (such as three-act or hero-centered) of drama. It is sometimes called a tragic “slice of life” because it is like a slice of real life, but with a strong tragic charge.

Also, in terms of narrative style, these films are close to minimalist narrative or poetic realism. Minimalism means that the story avoids big and exciting events and focuses on small and emotional details. Poetic realism means that reality is presented in a beautiful and artistic way, without distancing itself from the truth of life.

“Farewell Day” is limited to an emotional description of a tragic situation due to its lack of conflict, suspense, and narrative complexity. This limitation makes the film more like a painful nostalgic memory than a multilayered analytical cinematic drama.

Theme and Sociocultural Impact: Farewell or Reflection on Life?

The film’s main themes are death, loss, and family bonds. Moments such as Reza’s gift to his wife or his son’s driving lessons show his attempt to immortalize his presence and emotional legacy, reflecting a traditional and moralistic view of family bonds.

The lack of depth in the characters and the absence of meaningful conflicts cause the theme of Farewell to be reduced to a nostalgic and emotional feeling, without leading to a deeper reflection on death or family relationships. For example, dialogues such as “I want to say goodbye by making good pictures and memories” or the wife’s reaction to smoking, although emotional, remain superficial due to the lack of context.

The main theme, Embracing Mortality and Family Bonds, is universal and human, and it targets the heart and emotions for the Iranian audience and at domestic festivals such as the Tehran Short Film Festival. However, the subtexts, “a wife’s fear of the future or the pressure of the entrance exam on the son,” remained superficial and did not reach philosophical questions (such as the meaning of life).

The film’s worldview, emphasizing surrender to death, was conservative, and the social context, such as the entrance exam or economic problems (a car sale offer), seemed everyday without criticism or deep insight. The film balanced the local identity (the entrance exam, tea, etc.) and the global appeal (death), but the excessively everyday details seemed repetitive to the non-Iranian audience and lacked innovation or a fresh perspective that could distinguish it at international festivals.

The production by Soureh Film Club, affiliated with the Hozeh Honari, reflects the film’s value-based purpose (the importance of family, acceptance of death). But compared to Haneke’s “Love,” which sparked global debate with its philosophical and moral layers (voluntary death, love in old age), “Farewell Day” remains on an emotional level. The film does not address deep social issues (e.g., the Iranian healthcare system or the problems of cancer patients, etc.), and its impact depends on a superficial identification with death, not deep reflection.

2. Narrative and Conflict: Linear and Slow, Without Dramatic Beat

The film’s narrative is completely linear, moving chronologically from Reza’s painful awakening to his farewell on the beach from a third-person point of view. This structure is simple and appropriate for a short film, but the lack of flashbacks, sub-narratives, or alternating points of view makes the story monotonous and one-dimensional. The film’s initial hook, the painful scene of Reza’s scream and fall from the bed, is visually and emotionally powerful and immediately introduces the audience to his crisis. However, the inciting incident, Reza’s return from the hospital to spend his final days, occurs earlier and is not directly shown, which reduces the narrative power.

The lack of suspense, twist, or narrative surprise keeps the story predictable; it is clear from the beginning that Reza will die, and no questions or mysteries engage the audience. And there is no why or how to follow. Even moments like the car delivery or the father-son conversation, which could have created emotional suspense, quickly come to a conclusion. This lack makes the narrative predictable and monotonous. Adding emotional suspense (for example, the son’s hesitation about accompanying his father and challenging the family) could have made the rhythm more dynamic.

From a narrative structure perspective, “Farewell Day” lacks the classic elements of drama. There are no clear turning points that change the course of the story; the arrival of the car, Reza’s decision to learn to drive, or his gift to his wife are all emotional moments, but they do not act as catalysts or plot twists. Potential conflicts, such as the tension between the son and mother or the decision to sell the car, are resolved quickly and without elaboration. Even the ending of the film, which seems to narrate the moment of Reza’s death with an emotional cliché, is presented implicitly and without a dramatic climax.

This lack of narrative arc and resolution transforms the film from a dynamic drama into a linear, memoir-like narrative. This can be seen as a deliberate stylistic choice, but in the absence of a coherent narrative, the film’s emotional impact depends on the audience’s identification with the subject of death, not the power of storytelling.

In drama, resolution refers to the creation of a problem that needs to be resolved. In “Farewell Day,” potential issues (such as Reza’s illness, family tension, or a decision about a car) are introduced in passing and quickly resolved or ignored. For example, the young man’s smoking or Reza’s decision to sell the car and then change his mind could have created a resolution, but the decision is resolved without conflict or challenge. This lack of resolution and resolution contributes to the story’s linear, monotonous feel.

The main conflict of the story is Reza’s terminal illness and its impact on the family, but this conflict is presented passively. Reza and his family make no active efforts to deal with death (e.g., seeking treatment, deep reconciliation, or changing behavior), and the story proceeds in a context of pure surrender. The resolution in the farewell scene at the beach is emotional but passive and lacks dramatic intensity. The plot points and climax are not clear; the first turning point is expected to be a key moment such as accepting death or a family decision, but the narrative is content with everyday events (car delivery, conversations). The closest moment to a climax is Reza’s conversation with the boy about driving, cigarettes, and the farewell at the beach, but these moments are predictable and lack sufficient dramatic intensity.

The Dramatic Arc moves from pain to acceptance and peace, but this change occurs gradually and without clear turning points. Emotional peaks and valleys, such as Reza’s cry of pain or Sahel’s farewell, do not have a profound impact due to the lack of strong conflicts, and long descents (everyday conversations) slow down the rhythm.

A strong drama usually reaches an emotional or narrative climax that moves the audience. In “Goodbye Day,” emotional moments such as the embrace of a father and son, or Reza’s gift to his wife, attempt to create this climax, but due to the lack of background and suspense, these moments function more as emotional single moments than as the climax of a story arc. The end of the film, with Reza looking at the children’s play, could have been a tragic climax, but due to its implication and lack of dramatic buildup, its impact remains limited and is more like an abrupt break than a narrative conclusion.

From a cinematic perspective, a story is a narrative that has structure, conflict, narrative arc, and a change of character or situation, while a memory can be simply an emotional description without a specific structure. “Farewell Day” is closer to the definition of a memory due to its lack of conflict, turning point, and knotting. In this film, a subtle change is seen “acceptance of death for family members” or also the son initially distances himself from his father but in the end embraces him and a shallow emotional arc is formed. Ultimately, if we consider drama in its classical sense, it does not have drama, but if we define drama as the exploration of human suffering, it has been somewhat successful.

Reza, as the hero, does not have a clear goal (such as fighting an illness or repairing a family relationship), and his obstacles are purely physical, not dramatic.

This work is a prime example of dramas without dynamic plot, which, according to Eric Bentley’s theory, only show “situation” and not “change”, and are called “static drama”. “Still Life” (1974) by Sohrab Shahid Saless can be one of these examples.

To shine in international festivals, the script needs innovation, more complex conflicts, and deeper subtexts. However, in the context of domestic festivals, its emotional authenticity and human content can impress the audience. Deepening the characters with clear pasts and motivations, and adding surprise moments (like a family secret) could have made this a lasting work that captured not only the hearts but also the minds of the audience.

The “Don’t Tell, Show” Principle: The Definition Without Showing

The cinematic principle of “don’t tell, show” is ignored in “Farewell Day.” Reza tells his son twice, “You’re a good boy,” the second time with more emphasis. These compliments, which are part of an emotional farewell, are designed to encourage the boy, but the film shows no positive action from the boy or even any evidence of his past. He is irritable and aggressive, and no deep relationship with his father is depicted. This contradiction undermines the film’s believability. “Farewell Day” violates one of the key tenets of cinema by relying on dialogue.

The believability of “Farewell Day” falters at several key points. In addition to Reza’s unbelievable definition of his son, the driving lesson scene, in which the boy quickly, without practice, and without making any mistakes, is inconsistent with the realistic atmosphere and short format of the film. The unrealistic reactions of the daughter and husband to Reza’s illness also undermine credibility. The daughter, who should be in emotional crisis, is marginalized, and the husband, who should be in grief, has a normal reaction. These gaps turn the film into a simplistic narrative that is inconsistent with the reality of the pressures of a family in crisis and seems illogical. In comparison, “Love” maximizes credibility by accurately depicting the impact of the illness on Anne and Georges.

Layering and Complexity: Simplicity or Emptiness?

The film’s simple, linear narrative allows it to connect with a general audience and convey a sense of the tragedy of Reza’s gradual death. But this simplicity comes at the cost of a lack of layering and complexity. There is no subtext, irony, or psychological depth for analysts. The boy’s anger, the only sign of tension, does not need to be explored because its roots are not explored. The unrealistic reactions of the daughter and the wife also leave no room for reflection. In comparison, “Love” has philosophical layers (suspected death, love in old age). “Farewell Day” disappoints analysts with its flat narrative, because it offers nothing to ponder.

Social (such as economic pressure after death), psychological (the boy’s fear of the future), or philosophical (the meaning of death) subtexts are absent. Even the boy’s anger, which could be tied to fear or guilt, remains superficial.

3. Characters and Roles: Stereotypical and Shallow

Acting and Performance is one of the film’s strengths. Dariush Reshadad, in the role of Reza, must be able to convey physical pain (screaming, vomiting) and emotional peace (farewell, giving gifts) well, which he has succeeded in doing with his thin and fragile body. The actor playing the son (Ali Rad) has the potential to be effective in showing aggression, resentment, and crying, although his sudden reactions may seem a bit exaggerated. The actor playing Tima Taghizadeh’s husband and the young daughter have also acted in stereotypical roles (emotional and innocent supporter). Although the acting helps to make the emotions believable, due to the superficial characterization of the script, the actors have not had the opportunity to shine more deeply.

Reza, the protagonist, is a passive father, not an activist, who has no clear goal other than accepting death. The dramatic hero must fight for something, make a decision, change. The father, despite the emotionality of the role, has no significant transformation or effective dramatic action. The other characters are more reactive than active. There is no anti-hero in the story, and there is not even an antagonistic force that makes the father’s path difficult. Cancer could metaphorically act as an antagonist, but the script shows it as a mere medical condition.

The supporting characters (wife, son, and young daughter) act as a reflection of Reza’s pain, but their characterization is stereotypical and limited. The wife plays the role of emotional supporter, but her past or motivations are not explored in depth. The boy, under the pressure of the entrance exam and the death of his father, has the potential to conflict, but his reactions (aggression, crying) are superficial and not multi-layered. The young girl is a symbol of innocence, but has a decorative role, while she could have been the basis of the crisis or the emotional center.

Overall, the characterization of the film remains superficial. They are presented as ordinary, gray people.

The lack of background or psychological depth reduces the characters to simple types (the suffering patient, the worried wife, the nervous son). For example, the son’s anger or the wife’s pressures are not given much depth and are quickly forgotten. Even Reza, who is the center of the story, does not show much complexity beyond physical suffering and simple decisions (such as stopping the car). This limitation makes it difficult for the audience to connect deeply with the characters and makes the film dependent on the theme of death. We do not see any serious psychological crises in the children or the wife, and the little girl, who should naturally be the most vulnerable, remains in a completely neutral state.

In the end, one can ask, who is the hero of this family story? What is the goal and what are the obstacles to achieving it?

One of the strengths of “Farewell Day” is its ability to attract the audience’s sympathy. Reza’s painful images, such as his emaciated and scarred body or his vomiting next to a pizza vendor, convey a sense of human suffering and fragility. Family moments, such as eating together or children playing on the beach, despite their simplicity, convey a sense of authenticity and sincerity. These moments, combined with a fluid and affecting acting (especially as Reza), give the film a significant emotional charge.

Title and Names: Simplicity to the Point of Meaninglessness

The title “Farewell Day” and the names of the characters in the story are simple and straightforward, lacking in layers of irony, symbolism, metaphor, or depth. This title, like calling a film about war “Shooting Day,” adds no layer of meaning to the story. In comparison, Kiarostami’s “Taste of Cherry” (1997) refers to the bitterness and sweetness of life with its title. The names of the characters – Reza, Maryam, Narges – are also random and have no hermeneutical connection to the theme, merely everyday labels.

In a film set in Sari, one would expect the names to refer to Mazandaran culture or death, but this opportunity is missed.

4. Form and Aesthetics: Simplicity without poetic flight

The film’s dominant mood is one of sadness (Tone of Sorrow) mixed with a calm acceptance of death, and through painful scenes (Reza’s cry for morphine, vomiting, farewell on the beach) and tender moments (anniversary gift to wife, children’s play), it tries to keep the audience in an emotional swing. These familiar situations, the death of the father, the suffering of the family, create empathy for the Iranian audience, especially at domestic festivals such as the Tehran Short Film Fes

However, the mood sometimes becomes monotonous due to the lack of emotional variety (e.g., bitter humor or sudden hope) and remains dependent on the clichés of death drama (farewell, crying). Potential emotional contradictions, the boy’s anger against his father’s love, the young girl’s joy against death, are superficial; the boy’s aggression quickly ends in tears, and the girl’s joy is not contradicted by the father’s death. Adding moments of emotional multi-layering (e.g., Reza’s bitter laughter when giving a gift) or exploiting contradictions (e.g., the girl’s joy interrupted by her mother’s anger) could have made the mood more dynamic. Simplifying the everyday dialogue and adding silence at key moments would have deepened the emotional impact.

The film’s fluid and calm rhythm is consistent with its minimalist style and reinforces the sense of a painful memory. Linear editing, which avoids sudden jumps, helps the narrative flow. However, the lack of variation in rhythm (due to the lack of conflict or dramatic climaxes) can create a sense of monotony at times. For example, scenes of family tension or Reza vomiting could have had a stronger emotional impact if they had been accompanied by more careful editing. This limitation suggests that the film is not entirely successful in using editing to maintain the audience’s attention.

Visual Beauty and Symbolism: Poetic Realism or Missed Opportunities?

The film’s images are simple and functional, with scene details that make the Iranian family atmosphere believable. Scenes such as Reza falling from the bed with a bloody wound or the farewell on the beach have great visual potential, but the lack of creative framing or a distinctive color palette (visual aesthetics) limits the performance to a functional rather than artistic level. Natural lighting, without dramatic contrasts (such as light and shadow for death), misses the opportunity to create poetry (poetry).

The film does not use special techniques (such as long takes, split screens, or parallel montage), and the linear narrative and simple photography show that the director has chosen a minimal and realistic approach. This choice is acceptable for a short drama, but the lack of creative techniques (such as the mental view of Reza at the moment of farewell) makes the film remain technically conventional and undifferentiated. A simple technique, such as a gradual close-up on Reza’s face on the beach, could have enhanced the visual impact.

The cinematography, editing, and sound design lack creativity or strong impact. This simplicity is acceptable for a local short drama, but compared to the standards of festival short films (both in Iran and internationally), the film remains at a conventional level. Technical aspects, such as the script and performances, rely on primal emotions rather than enhancing the story, and miss the opportunity to create a lasting cinematic work.

Symbolism

Symbolism is also weak in the film. For example, the beach could have been expanded as a metaphor for the passage of life or the cycle of death and rebirth, but it remains merely an emotional location for a car trip at the request of his daughter. Or the car, which could have been a metaphor for the future or the family’s freedom, is reduced to an asset by the decision to sell. The kite on the beach, which had the potential to symbolize the liberation of the soul, appears fleetingly and without visual emphasis. The anniversary gift also fails to become symbolic due to the lack of a narrative background. “Goodbye Day” is cautious in its use of symbols, and its visual poetry remains underdeveloped.

In the final moments on the beach, Reza stays in the car, and while his wife gets out of the car and goes to the children playing and looking at the kites, Reza tells his wife through the car window to keep the car and not sell it, and it seems that there is no sadness or problem after his departure, not even financial and material problems. It seems that everything is normal and natural, and the only thing missing is his physical presence, so the main and symbolic moment of the drama is lost.

Direction and Innovation: A Conservative Performance Without a Signature

Farzad Ranjbar Nazari’s direction is theoretical, simple, and focused on conveying emotion. The choice of scenes such as Reza’s painful cry or the beach farewell demonstrates his understanding of the drama, but the lack of a distinctive visual style (Direction Signature) or creative techniques (such as long takes, flashbacks, or non-linear narration) keeps the performance within the conventional framework of family drama. Originality is absent in the performance; familiar elements (tea, cigarettes, beach) are presented without a fresh perspective.

Memorable Moments (Memorable Moments) such as the gift giving or the boy’s crying do not become iconic due to the lack of visual emphasis (such as close-ups or impactful music).

The editing between scenes (such as the transition from the house to the pizzeria or the beach) is smooth and simple, without technical complications (such as parallel montage or non-linear editing) and without creativity. The lack of dynamic editing or emotional cuts (such as a quick cut to the moment the boy cries) makes the film’s rhythm too slow and monotonous for a short work (which should be concise and impactful). This slowness exacerbates the weakness of the script’s narrative rhythm.

The use of directorial techniques such as a mental view from Reza’s point of view or silence at key moments could have created a personal signature. The addition of a novel idea (for example, a narrative from the perspective of a young girl) or universal symbols (for example, the sea or a kite as a metaphor for death) could have enhanced innovation. Deepening the social context by referring to economic problems (for example, a dialogue about the future of the family) and using Mazandaran folk music also increased authenticity and appeal.

The costume, set, and makeup design are all fairly typical, sadistic, realistic, and believable.

The film’s slow rhythm is consistent with minimalism and conveys a sense of time passing. The linear editing helps with fluidity, but the lack of rhythmic variety and climax creates a monotony. The tense scenes (vomiting, the wife’s protest) could have been more effective with more precise editing. In comparison, “Love” made the suffering tangible with its slow but purposeful rhythm. “Farewell Day” succeeds in its calmness, but its monotony tires the audience.

5. Final Assessment: A Memory That Touched the Heart, but Not the Mind

“Farewell Day” is a moving story that, relying on the universal theme of accepting death and the believable details of an Iranian family, creates moving moments, especially in the painful opening scene and the quiet farewell on the beach. But from a script perspective, it resembles an emotional memoir more than a coherent cinematic drama. The lack of active conflict and obstacles, clear turning points, suspense, and deep characterization turns the narrative into a sequence of emotional moments that draw strength from the identification with the death of a father (especially for an Iranian audience) rather than from its dramatic structure.

The film’s presence at the Tehran International Short Film Festival demonstrates its potential to capture the attention of audiences, but compared to the outstanding works in the minimal drama genre, “Farewell Day” feels unfinished. By choosing a minimal and realistic approach, the filmmaker has pursued a bold goal, but the lack of narrative coherence and thematic depth prevents it from fully realizing this goal. Ultimately, “Farewell Day” is not a coherent cinematic drama, but a tragic memoir that shines in its emotional moments but fails to present a lasting narrative.