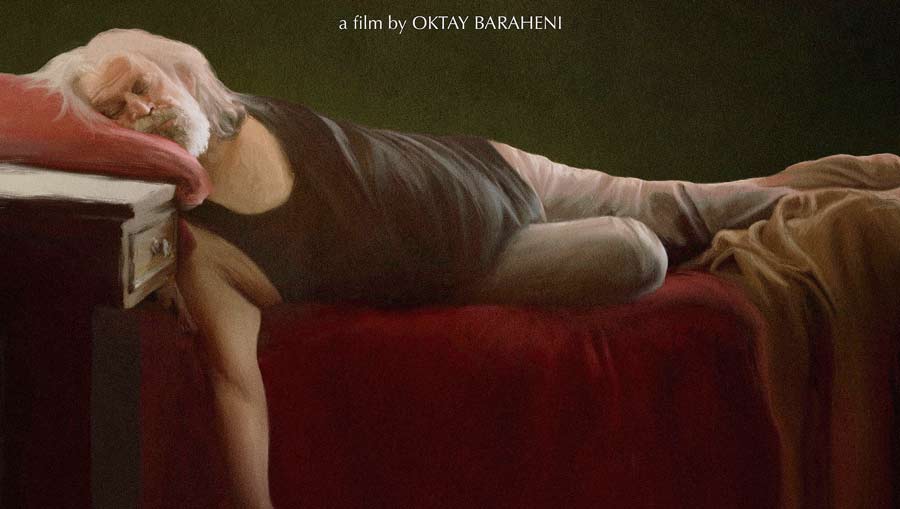

Nasser Taghvai; Author and Cinematographer who initiated a new wave in Iranian cinema

Nasser Taghvai, a veteran Iranian filmmaker and writer, has died at the age of eighty-four.

According to Artmag.ir, Marzieh Vafamehr, Nasser Taghvai’s wife, announced his passing.

The late Nasser Taghvai, was born on July 12, 1944 in Abadan. The films Captain Khorshid, O Iran, and Unruled Paper are among his most prominent works.

Nasser Taghvai, is considered one of the country’s auteur filmmakers. He was one of the pioneers of the New Wave movement in Iranian cinema. He is also considered one of the contemporary storytellers.

Marzieh Vafamehr, the late wife of Nasser Taghvai, wrote about him:

Nasser Taghvai, an artist who chose the difficulty of living freely, achieved liberation.

Let us remember his flight.

He loved plants, let us plant trees in his memory.

He loved light, let us light our candles.

He loved white clothes, let us wear white in his memory. He loved literature, let us read in his memory.

He loved cinema, let us watch in his memory.

Let us honor his memory by playing and listening to music and watching art. Nothing else.

His path is full of paths

In a message following the passing of Nasser Taghvai, a prominent Iranian artist, Mohammad Reza Aref, First Vice President, said, while expressing condolences for this loss, that Taghvai’s artistic legacy will inspire future generations of filmmakers.

He added: “That learned artist was one of the enduring figures in the country’s cultural and artistic scene, who played an important role in the development of Iranian cinema with his valuable works and creative vision, and made his name immortal in the cultural memory of this land.”

Hamed Jafari, CEO of the Farabi Cinema Foundation, said on the occasion of the passing of the thoughtful filmmaker Nasser Taghvai: “Master Taghvai was not only an outstanding director, but also the architect of a new perspective on Iranian narrative; a perspective that redefined a different meaning and identity in Iranian cinema in his brilliant works. Without a doubt, Iranian cinema is indebted to the vision, effort, and honesty of Master Nasser Taghvai; a filmmaker who immortalized the human spirit in the form of images in his works.”

The veteran artist, the cheerful Master Nasser Taghvai, is one of the pioneers of a movement in Iranian cinema that some historians later called the New Wave of Iranian Cinema. He has been described as an auteur filmmaker.

The Artists Evaluation Council of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance awarded Taghvai a first-class artistic certificate in 2004.

He received the Statue of Merit for a lifetime of artistic achievement at the 13th Iranian Cinema Festival and was honored at the 14th Iranian Short Film Association.

The late Professor Nasser Taghvai was attracted to television before starting his career in cinema and gained attention by making a television series.

He made the television series “Uncle Napoleon” in 1976, which was well received by the audience and established him as a successful filmmaker in the intellectual space and among the general public.

In 1988, Master Taghvai won the Bronze Leopard Award at the Locarno Film Festival for the film “Captain Sun” made in 1986. “Calmness in the Presence of Others”, “Paper Without Lines” and “Sadegh Kurde” are among Tafgvai’s other works.

The funeral ceremony for Nasser Taghvai, attended by artists and cultural figures, was held on Thursday, October 14, at the Cinema House.

In this ceremony, figures such as Sirous Moghadam, Hamed Behdad, Alireza Davoudnejad, Reza Kianian, Rasoul Sadrameli Shahab Hosseini, Panthea Panahiha, Amin Hayaei, Jahangir Almasi, Seifollah Samadian, Houshang Golmakani, Azita Hajian, Hamid Pourazari, Kourosh Soleimani, Iraj Rad, Habib Rezaei, Touraj Aslani, Javad Toosi, Mohammad Charmshir, Ahmad Talebinejad, Setareh Eskandari, Katayoun Riahi, Sara Bahrami, Ali Sarabi, Mehdi Miami, Kahbod Taraj, Mahmood Gabarloo, Leili Farhadpour, Tina Pakravan, Atabek Naderi, Soheil Mahmoudi, Soheila Golestani, Amirshahab Rezavian, Maral Bani Adam, Kaveh Foladinasab, Saeed Poursamimi, Mostafa Kiai, Majid Tavakoli, Majid Barzegar, Iraj Raminfar, Yasna Mirtahmasb, Mohammad Valizadegan, Ali Oji, Farid Sajjadi Hosseini, Mojtaba Mirtahmasb Hossein Mahjoub, Abdolreza Akbari, Amir Hossein Sharifi, and others were present in the courtyard of Building No. 2 of the Cinema House.

Mohammad Hosseini Baghsangani, a researcher of culture and art, wrote in IRNA:

The late Nasser Taghvai is not only one of the pillars of the new wave of Iranian cinema, but also one of the rarest examples of thoughtful and committed filmmakers in the Third World.

Nasser Taghvai, is a filmmaker, documentary maker, and writer who holds a unique and sometimes tragic place in the history of Iranian cinema; a figure who was caught between love for his hometown and alienation from power structures, remained suspended between creativity and censorship, and despite his enormous contribution to the formation of modern Iranian cinema, often remained on the fringes of the global fame of his contemporaries. His life and works are a full-length picture of the history of Iranian intellectuals in the contemporary era; an intellectual who has lived on the border between homeland and exile, silence and outcry, art and prohibition.

Gilgamesh Publishing, published a book a few years ago called “The Cinema of Nasser Taghvai.” A valuable work by Saeed Aghighi, accompanied by Reza Qias, who has revealed many untold stories from the beautiful and enduring world of Nasser Taghvai.

After reading this book that same year, I wrote down what I had learned from this book and Nasser Taghvai’s cinema, and the news of Nasser Taghvai’s passing prompted me to rewrite this article with a different perspective and present it to those interested.

Roots and Hometown: The South as Destiny

Nasser Taghvai, was born in the summer of 1941, in the midst of World War II, among the thick green palm trees of an Arab village in Khuzestan province. He himself said that he was born in the heat of the war, “among a forest of green palm trees,” and from the very beginning he had an unbreakable bond with the south of Iran. Iran was his homeland, Khuzestan his province, and Abadan his love. This emotional triangle shaped his artistic destiny.

His childhood was accompanied by constant travel to the southern ports. His father was a customs officer and the family was constantly moving from city to city. Taghvai says that during his elementary school years, he spent every year in a different city and when he returned to Abadan at the age of seven, he saw himself as “a teenage Sinbad.” He was interested in literature in high school, but studied mathematics. However, from those years, he turned to writing short stories and became fascinated with new methods in literature and narration.

Despite all these cultural tendencies, he himself says: “My personal life does not have any interesting scenes. My only luck is that, with an unwanted birth, I have lived for half a century like a great person alongside a nation.” In this bitter and poetic sentence, lies his philosophy of life: a person who stands in the middle of society and power, alongside the people but outside the official circle.

The beginning of the path on Iranian National Television

The 1960s were the birth of Iranian National Television and at the same time the emergence of a new generation of artists who sought to define a kind of cultural and thoughtful cinema. Taghvai was one of the first to move from literature to images. He says: “We were not interested in entering the mainstream cinema; a cinema that was a mixture of Turkish, Indian and Arabic films.”

Taghvai was one of the first to move from literature to film

With the establishment of the Iranian National Television and at the invitation of Farrokh Ghaffari, these talented young people – who were previously members of the Film Institute – joined television. Ghaffari was, in Taghvai’s words, the “godfather of Iranian cultural cinema”; someone who opened a new path for Persian film and trusted the new generation.

In the first two years of television’s activity, Taghvai made a series of documentary films; works such as Taximeter, Illiterate Unreaders, and Sun Hairdressers. These films were made with a small budget and limited facilities and were designed to be shown on regular television programs. He considered these works not documentaries in the serious sense of the word, but practical exercises for entering professional cinema.

According to him, Ghotbi, the director of the television at the time, trusted him and his contemporaries and said: “The work that is produced will eventually be shown one day.” This sentence gave a young man like Taghvai hope to continue working, even if the screenings of films were postponed. Thus, television became his first practical school in cinema.

The Birth of the New Wave and Its First Victim

The 1960s were a period of transformation in Iranian cinema. A new generation of filmmakers, inspired by modern literature and social concerns, created a different kind of cinema. The year 1968 was a turning point in this process; Dariush Mehrjoui made COW, Masoud Kimiai made Qeiser, Ali Hatami made Hassan Kachhel, and Nasser Taghvai made his first feature film, Tranquility in the Presence of Others.

The film was based on a story by Gholamhossein Saedi, a writer whose friendship and collaboration with Taghvai continued for many years. But the film’s fate was the tragic fate of censorship in Iran. Tranquility in the Presence of Others was confiscated after a few private screenings, remained in storage for six years, and was finally shown in cinemas for only eleven nights. After that, it was completely banned. Taghvai later said: “This film was the first major victim of the intensification of censorship in Iranian social cinema.”

The film took a bitter, psychoanalytic view of the decline of empowered men and the breakdown of the family in modern society; concepts that were taboo at the time. This view made it a work that was both progressive and sacrificial.

From Literature to Cinema: A Sanctuary of Thought and Freedom

Taghvai, believed that the roots of the New Wave were in modern Iranian literature. He recalls that censorship initially targeted poetry and fiction, which drew writers to cinema. Gholamhossein Saedi, was a pioneer of this movement, and many writers of his generation, including Taghvai, realized that cinema could be a new realm for expressing thought.

Taghvai, has spoken of the bitter experiences of his works being repeatedly banned and halted: “In the past five years, three of my films have been closed half-finished.” He sees censorship not only as a ban on screenings, but also as an existential threat to the artist. In his view, in a censored society, the artist is forced to speak indirectly: “He must speak by not saying, show by not showing.”

In such circumstances, meaning is transferred from the surface of speech to the depth of the structure. Taghvai says: “The meaning of modern writing is not in what is written, but in the whiteness between the lines.” He extends this principle to cinema: the visual structure and the way of narration carry meaning that remains hidden from the eyes of the censor.

According to Taghvai, this characteristic – speaking in silence and giving meaning in structure – was transferred from modern literature to Iranian cinema and caused Iranian filmmakers, unlike their Western counterparts, to always seek to express their personal opinion and position in their work. This also caused Iranian cultural cinema to be noticed at international festivals; because behind every image, a protesting mind and metaphorical language were hidden.

Documentary Legacy and Ethnographic Perspective

Before entering feature films, Taghvai, was significantly active in the field of documentary. His works during this period, including Bad Jinn, Nakhlestanhaye Junob, and Arbaeen, had ethnographic and cultural aspects and focused on recording the rituals, beliefs, and lives of the people of southern Iran.

In these films, he explored topics that were unknown or even considered forbidden at the time; including the “Zar” ritual in the south, which had roots in African culture and the history of slavery. Taghvai depicted these rituals with a poetic yet documentary perspective and, for the first time, recorded the connection between history, geography, and the collective psyche of the people of the south in the form of images.

His perspective in these documentaries was not simply ethnographic; rather, it was a philosophical search to find “Iranian identity” in the neglected layers of history and culture. He had said: “Without geography, there is no history. The South, for me, is a geography that extends to infinity.”

From “Tranquility in the Presence of Others” to “Captain Sun”: Splendor and Isolation

In the 1960s, Taghvai once again made his mark in the history of Iranian cinema with the film Captain Sun (1986). The film was an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s novel To Have and Have Not, but he transferred the story to the atmosphere of southern Iran; to the ports and seas that he himself knew and had lived in.

Captain Sun is one of the few successful international adaptations in Iranian cinema; a film that, with its stunning atmosphere and brilliant performance by Dariush Arjomand, broke the boundary between literature and cinema. Domestic critics called it “a film that divides the history of Iranian cinema into two periods, before and after.” However, it was not widely seen internationally.

Intellectualism, Politics, and Loyalty to the Country

Nasser Taghvai, was not only a professional filmmaker, but also a social intellectual who constantly oscillated between love for the country and criticism of political structures. He never left Iran, but always lived in a kind of internal exile. He had explicitly stated that the political regimes in Iran complemented each other: “One prevents the screening of films, the other prevents production.”

At the same time, he never joined the propaganda or affiliated cinema. In his view, cinema was not a tool for entertainment or propaganda, but a mirror for understanding man and society. This intellectual independence deprived him of the support of official institutions and caused many of his projects and films to remain unfinished.

Taghvai and his place in the history of Iranian cinema

Despite all the obstacles, Nasser Taghvai, is considered one of the founders of auteur cinema in Iran. His career includes thirteen short stories, thirteen reportage and documentary films, three short fiction films, six feature films, and a sixteen-hour television series. However, the value of his work lies not in the quantity, but in the quality that is seen in each work: attention to detail, respect for geography, understanding of society, and loyalty to a personal cinematic language.

He was always in search of a connection between literature and cinema and considered himself “a writer who thinks with images.” In his works, from Calm in the Presence of Others to Captain of the Sun, the Iranian man is depicted in the face of power, history, and the inevitability of geography.

Final Words

The late Nasser Taghvai is not only one of the pillars of the new wave of Iranian cinema, but also one of the rarest examples of a thoughtful and committed filmmaker in the Third World; a filmmaker who came from literature and remained loyal to poetry and philosophy, who both loved and criticized his homeland, and ultimately lived on the border between being seen and being ignored.

His legacy is a reminder of the fact that cinema, in a country like Iran, is not just an art form of the image, but also a language of protest, historical memory, and a refuge for the indirect expression of truth.